Four decades later, in 1859, four women - regarded as social visionaries of the day - were poised to do just that, setting up refuges in London and Liverpool which were, in effect, way stations from which the children were shipped across the sea to the supposed bright promises of Canada.

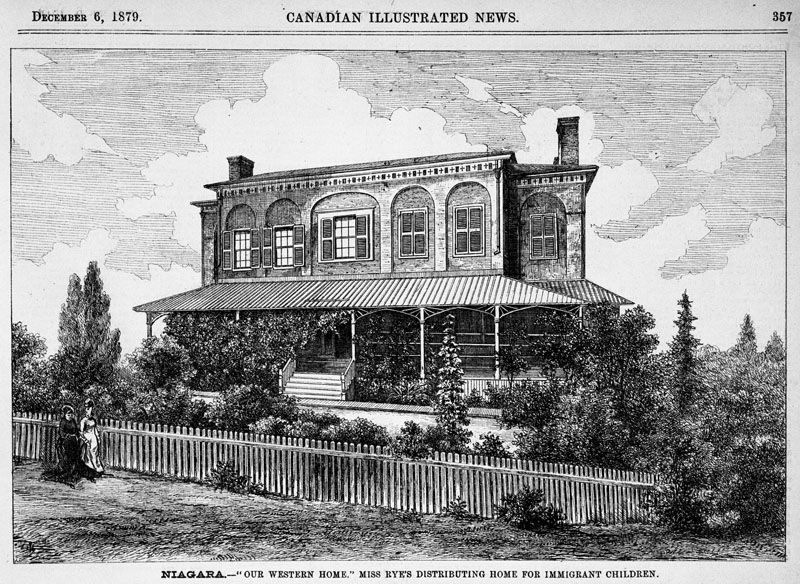

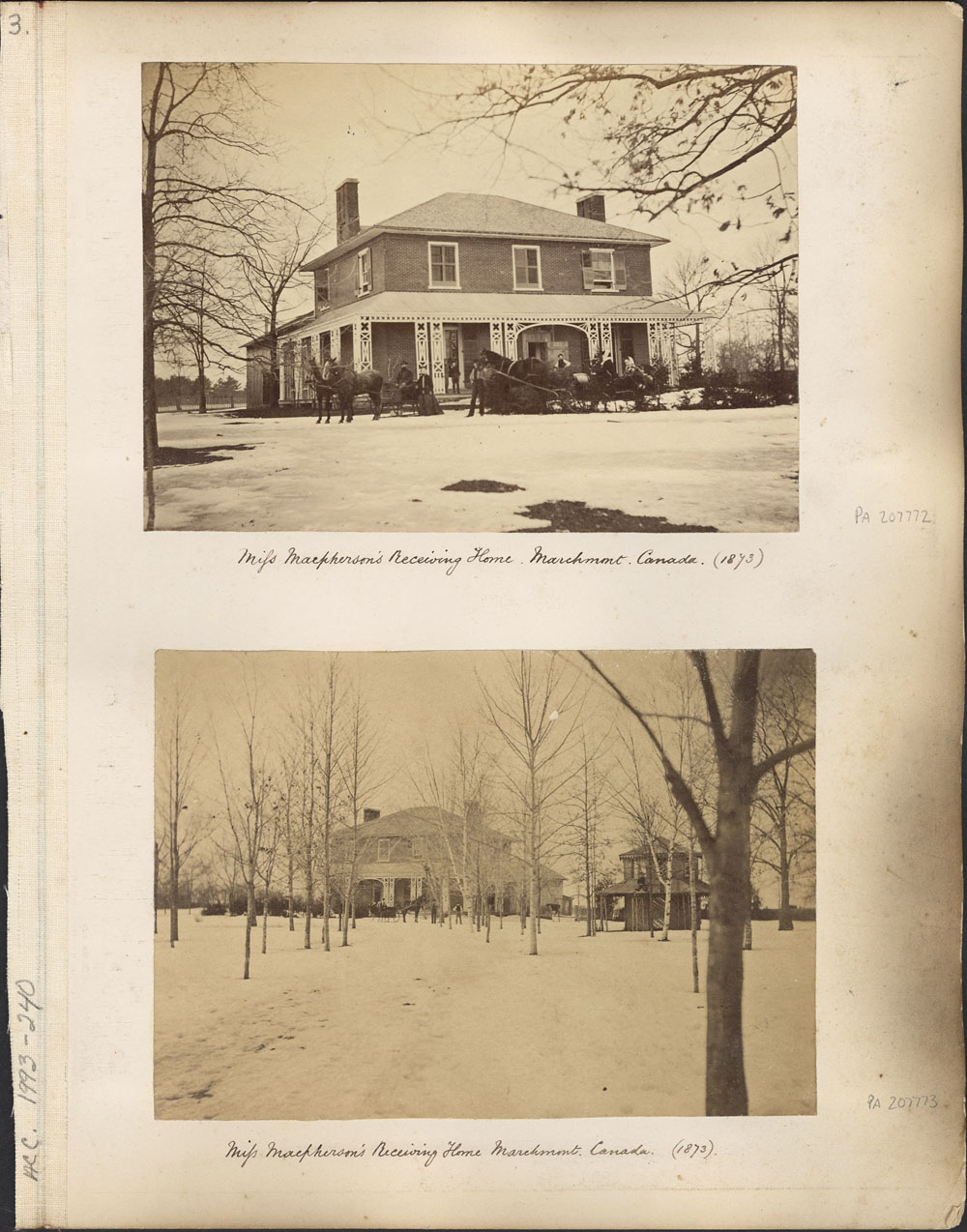

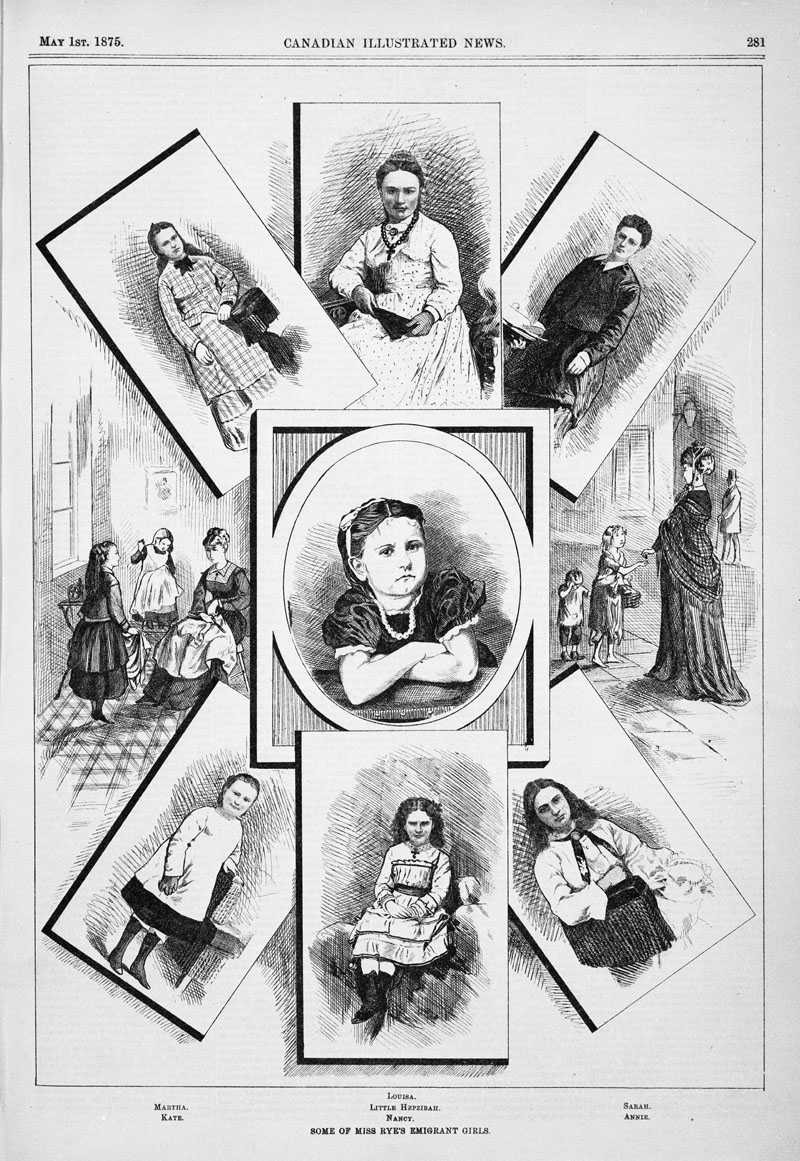

The most prominent of these women was Annie Macpherson, who along with her sisters Rachel and Louisa sent almost 14,000 children to Canada over many decades. Another of these women was Maria Rye, a strong-willed woman whose children, all girls, were sent from London to "Our Western Home" in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, from which they were subsequently distributed as household help but usually ended up as labourers in the farms of southern Ontario.

At its peak, in the years immediately before and after 1900, dozens of individuals and small organizations were sending children to Canada, mostly youngsters whose parents lived in poverty, or else waifs found where they were left - in blankets or baskets in the hope someone else would care for them.

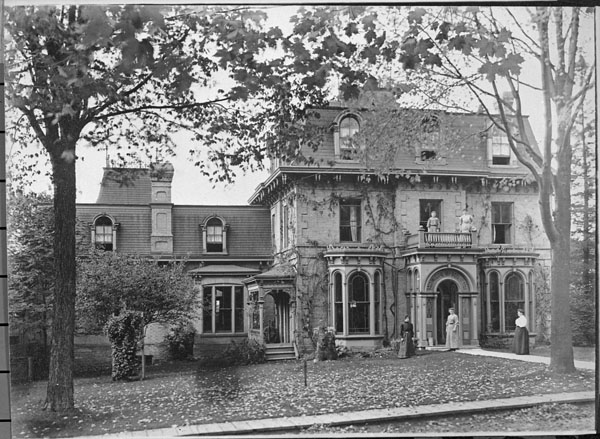

The most famed figure of child emigration was Thomas John Barnardo, whose work, begun in 1870, grew to large proportion under his zeal. He trained in medicine and theology and, after an aborted plan to go to China as a missionary, he set up several refuges for children in London's east end. Over the history of the movement, Barnardo's organization sent roughly 30,000 children to Canada, to homes he established in Peterborough and Toronto and, for a time, to a farm he set up in Russell, Manitoba.

The children (most of whom were age 8 to 16 though there were many who came at 4 and 5 years of age) were almost always taken first to Ontario receiving homes in Belleville, Stratford, Niagara-on-the-Lake and Toronto. Advertisements were usually placed in local papers announcing the arrival of another shipment of children and inviting farmers to visit the home for a prospective "home boy" or "home girl."

The child was only rarely adopted but was indentured, the farmer in return providing lodging, a modest allowance (to be placed in a bank account ostensibly in trust until the child reached maturity) and schooling. Very often, few of these obligations were met. There were, as might be expected, a great many cases of abuse of all kinds, physical, emotional and mental. Children were often returned to the home as being unsuitable - too small, too slow, too difficult.

In many cases those who sent the children and those in Canada who oversaw their placement had high motives. They believed that life in the clean air of the new land, along with hard work and healthy discipline, would assure them of a wholesome development. Often, too often, this was simply a naive dream, with no understanding of the needs of a child and no awareness of the conditions in which they were placed.

From its very early years, the practice of sending children from Britain to Canada was the subject of investigation and high controversy. Only four years after it began, a British commissioner spent several weeks in Canada visiting the homes in which the children were received and then the farms on which they were placed; he was severely critical of the random nature of the entire operation, both in the selection of farm families receiving the children and the later supervision of their placement which in the case of Maria Rye's was virtually nonexistent. It is testimony to the influence of market demand for cheap labour that despite this early and severe criticism, the schemes were to continue well into the 20th century.

Some youngsters fared reasonably well. These were in most cases, very young children who, being too young to work, were taken into families simply as children, not as workers. But quite apart from the numerous youngsters who suffered great physical or emotional abuse - isolated on farms with virtually no supervision and where adult farm labourers were often undesirable wanderers - the very practice of child emigration must be viewed with deep scepticism. It uprooted children at the most crucial period of their lives, shipped them like commodities, placed them in a foreign environment and set them to work; they were robbed of childhood.

By the 1920s, serious voices in Canada were questioning the principle of child emigration. In the summer of 1924, Charlotte Whitton, the director of the Canadian Welfare Council, said that the schemes were inhumane. James S. Woodsworth, the respected Member of Parliament and later first leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, added his opinion in the House of Commons: "We are bringing children into Canada in the guise of philanthropy, and turning them into cheap labourers."

Also in 1924, the Bondfield Commission came from Britain with the same purpose that a one-man British Commission had in the earliest years of child emigration: to inspect the homes and examine the welfare of the children. That November it offered the opinion that only children over 14 (school-leaving age) should be permitted to emigrate.

For the remainder of the 1920s, only older teenagers came to Canada. Then as the economy of the country began its downturn, and the labour movement stepped up its longtime opposition to the programs, the number began to dwindle. In the end, while child emigration was questioned by men and women in Canada who saw its numerous flaws and its primitive attitude toward children, it was not enlightened understanding which drew the curtain upon this long career of Canadian history. It was the Great Depression.

Over 100,000 “home children” were sent from the U.K. to Canada to work as labourers, from 1869 through to the 1940s. The podcast finds out who they were and what happened once they arrived here. Plus, Alan Dilworth tells the story of his grandfather, Tom Selby, who arrived in Canada at the age of eight.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

See also Child Labour.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom