Indigenous art in Canada has a strong and varied tradition which defies general classification. Across the country the carvings, embroidery and beadwork produced by Inuit, First Nations and Métis are distinctly connected to place and community.

.

Contemporary Indigenous art in Canada has built upon this strong foundation, with diverse artists interpreting their reality in new and ever-changing media. First-wave contemporary artists like Benjamin Chee Chee, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Beam and Kananginak Pootoogook and carvers like Bill Reid and Joe David — having built on the traditions of Charles Edenshaw — have given way to Duane Linklater, Kent Monkman, Brian Jungen, Rebecca Belmore, Annie Pootoogook and many more.

.

Indigenous writers in Canada also defy classification. Poets, playwrights and novelists like Rita Joe, Eden Robinson, Tomson Highway, Thomas King, Lee Maracle, Richard Wagamese, Joseph Boyden, Michael Kusugak, Waawaate Fobister and others have brought Indigenous literature into the forefront of literary discussion in Canada. Rich imagery and inescapably political themes lay bare the pain of the past while celebrating cultural expression and moving through present struggles.

.

Like their more-established peers, the artists and writers of the Indigenous Arts & Stories program are exploring their identity through self-expression while pushing back against simple and stereotypical categorization. These writers and artists are coming of age in an era of renewed activism, celebrating Indigenous identity while creatively rejecting appropriation, colonialism, and assimilation. These ten works, five writing and five arts, are representative of the future of Indigenous writing and art in Canada, and the future is bright.

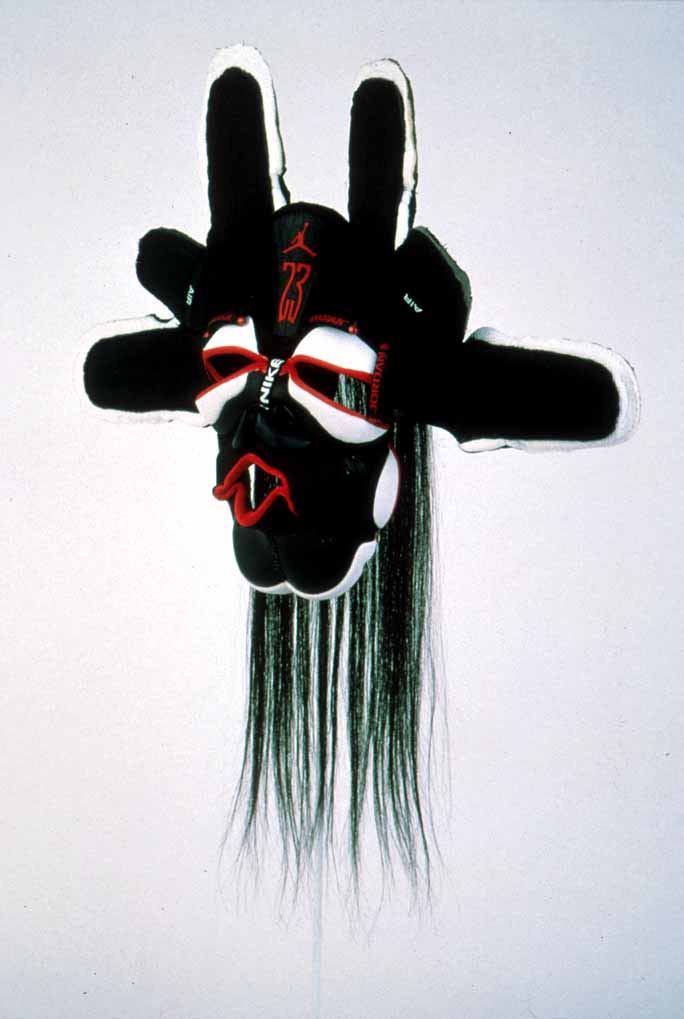

Living The Dream Since 1492

Artist Statement

.

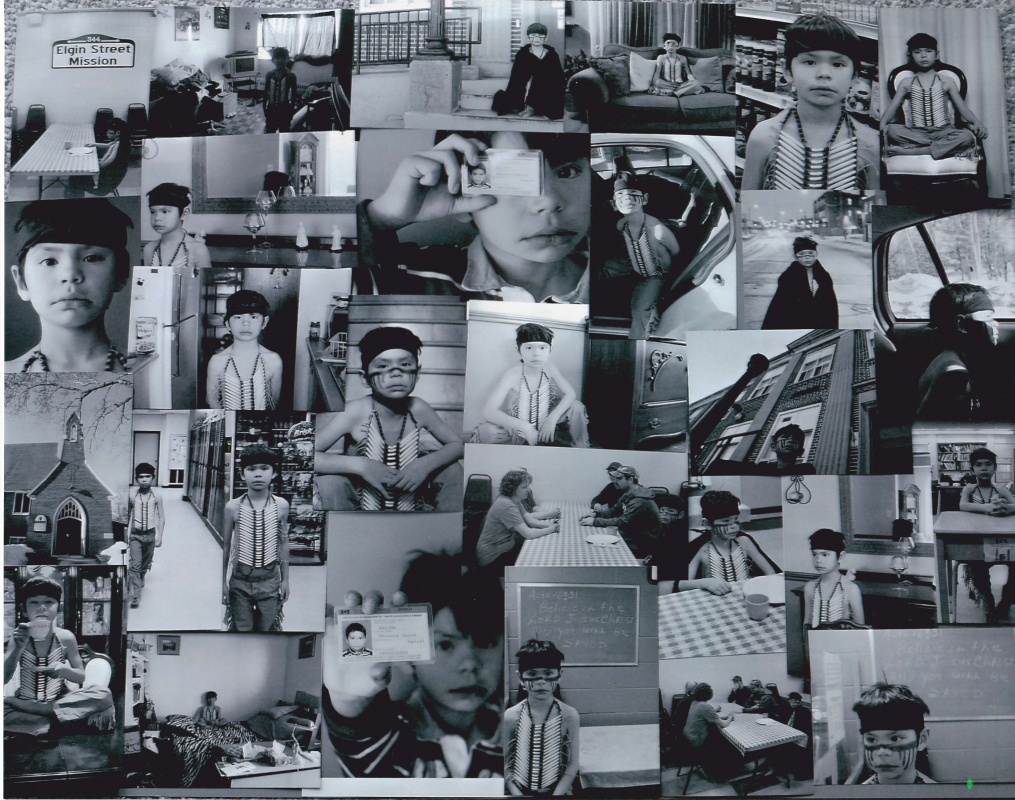

Brandan Wilson photographed his seven-year-old brother Phoenix in a homemade stereotypical "Hollywood Indian" costume doing things around Sudbury that have a direct impact on contemporary indigenous life.

.

“Just him in and around the city, in places like the grocery store, back of a police car, soup kitchen, church, rectory, and school. There are two larger photos of Phoenix holding his status card. No other culture in Canada is identified by the Canadian government by ID cards. I wanted to show that my brother, myself, my family, my culture is more than just a card and ‘civilization’ wasn’t civilized.”

With Friends

Artist Statement

.

This painting re-imagines the moment of my mother’s removal from her birth family as a child of the 'Sixties Scoop.' My mother shared her memory of this moment with me when I was a teenager, long before making art was of any interest to me. Over the years I thought about her story and about all the other children who had been needlessly taken from their own families only to be haphazardly placed into another family or imprisoned within mission schools. The reality of it seemed absurd and impossible, that a man of no familiarity could go to another’s house, abduct the children and escort them into an unknown and horrifying future like some perverse Pied Piper. Certainly it doesn’t seem too far removed from the morbid fairy tales and cartoons which I would read as a child.

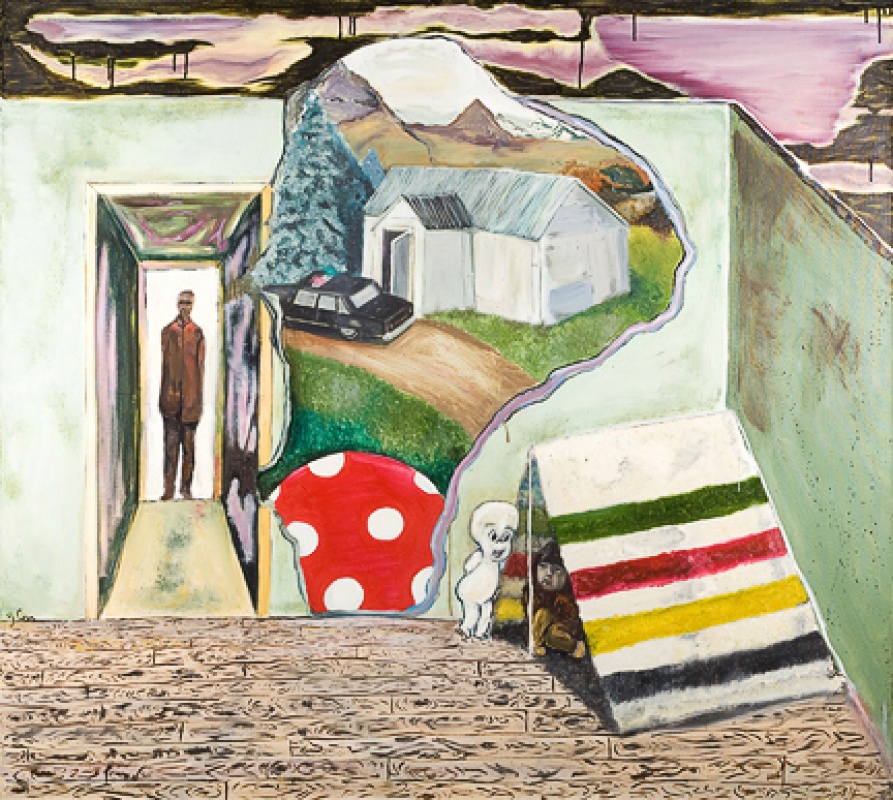

Going Back or Home

Artist Statement

.

Going Back or Home is about the will power of newer generations to head back and to look for ancient teachings. There are a few different factors at play and the composition is definitely influenced in a more contemporary way. The mixing in street art and the woodland lines into the work gives is a real fragmented look, strong color contrast glazing and numerous dripping paint effects make way for different interpretations of the image. Being a person of mixed descent, I always have felt a desire to grow closer to my roots, be that in Africa, Cape-Verde or here in Canada with my Anishinabek family and my mother from the French River area.

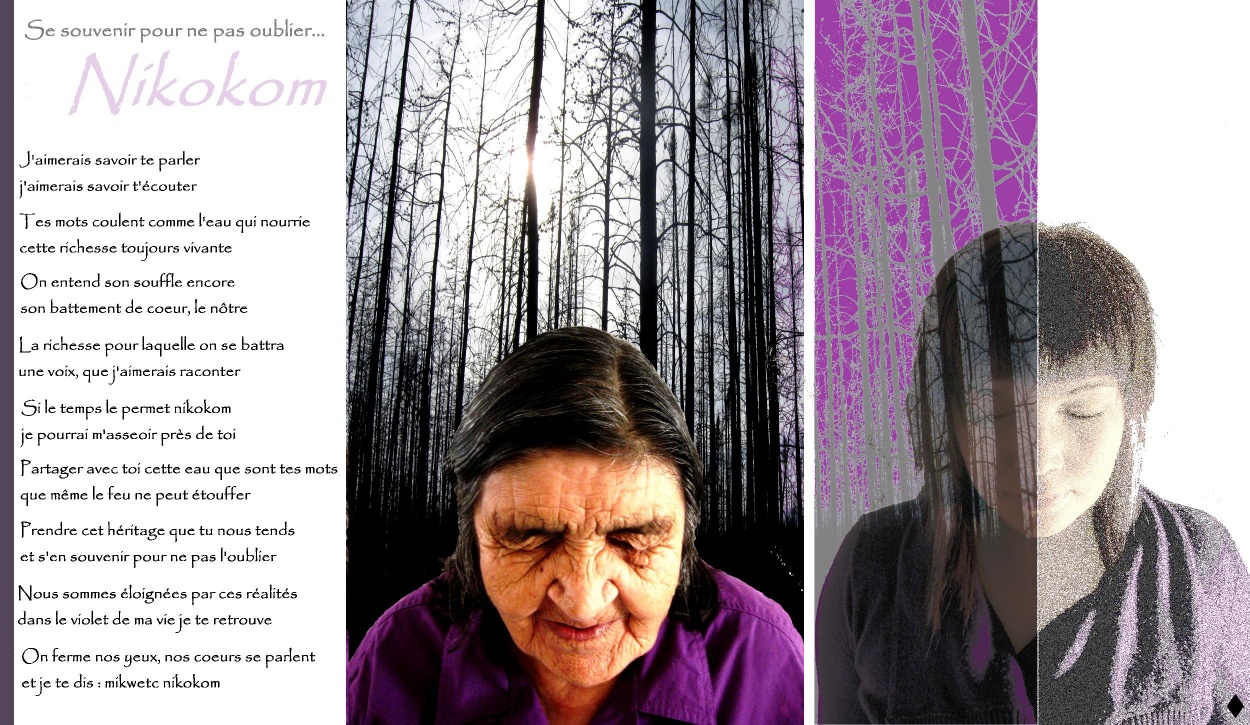

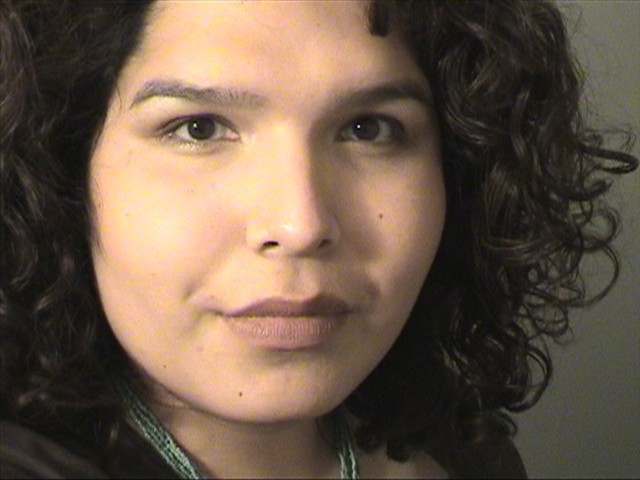

Se souvenir pour ne pas oublier, Nikokom

Artist Statement

.

Tell, talk, share. I wanted to represent the reality of a fragile language that we must safeguard. Nikokom, with whom I never really had the chance to talk, made me realize that this is a part of me that I can’t understand, and time slips. So I use the image, photography, to allow myself to freeze time, and make clear the ever too present gap that separates.

.

I allow myself to write to her, as if she were able to understand how much I want to change this reality, and that I would do whatever it takes to get there. Art allows me to say what might not often be seen. And in this case, art allows me to see what I can’t tell her.

Tarnikuluk

Excerpt

.

Tulugak stood on the sturdy telephone pole in front of a church in the community. To the people gathering at the small building, he only appeared as a raven observing the view. It seemed as if the whole community had come to the church today, as they were overflowing out of the structure, spilling onto the street. There was a mess of vehicles parked; pick-up trucks, small SUVs and dozens of snowmobiles. Weepy singing lilted out of the church as the people sang their sorrows. A death had come to the community again and this was the funeral for yet another young soul that tripped into the idea that dying by one’s own hand might make their sadness end.

.

Another soul joined Tulugak on the telephone pole in the form of a smaller, less majestic raven. She was shy and hesitant, confused at why there were so many people below them. Tulugak waited for her to gain enough courage to speak. Several moments later, in a squawk, she asked, “Is that my funeral?”

.

Author Statement

.

My story speaks about the intergenerational effects experienced by the spirit of a young Inuk woman who has recently committed suicide. On this journey to the afterlife, she is guided by Tulugak, a raven in Inuit mythology who is being punished for his mischievous ways and causing the death and rebirth of the sea goddess, Nuliajuk. Historically, Inuit believed in spiritual reincarnation of all living creatures. I took this idea and played around with it, but it still accurately portrays how communities deal with the tragedy of suicide. I did not name a particular community as this story belongs to all Inuit who have experienced the death of a loved one by suicide. From 2011 to 2013, there were 105 deaths by suicide in Nunavut, the youngest being eleven years old.

.

Tarnikuluk is an Inuktitut word meaning "little soul."

.

Read Aviaq Johnston’s full story here.

Maternal Ties

Excerpt

.

It was a teacher and the priest from St. Mary’s who brought the men from the museum over to my grandparents place. They were bringing them around the reserve because these men were looking for things to put on display in their Banff museum. They saw my grandma wearing her dress as she served them the little food and tea they had in their cupboards and offered her $70 for her dress. Grandma says that the $70 she got for her dress was enough to get them by with food for another two winter months.

.

Artist Statement

.

The loss of Aboriginal peoples’ material culture has been part of the personal devastation of many families. It is an era in which anthropologists, archeologists and many western institutions set out to 'preserve' living cultures that they believed were dying away. Their methods of preservation were to possess, catalogue, archive and store away the personal and sacred materials that helped to maintain Aboriginal identity.

.

With my story I hope that I have been able to express the loss experienced by five generations of an individual family of women. It is not just the loss I am expressing but the hope for the future as well. The narrator, Mary Stands Alone, looks back from the not too distant future at a moment of pride for herself and her family.

.

Read Sable Sweetgrass’ full story here.

The Hiatsk

Excerpt

.

He sighs, gets up and starts to return home in the dark completely at ease. Out of nowhere a small animal runs across the path, it means no harm, but Joseph is startled and trips falling head first into a deep crevasse. He yells for help though he knows he’s too far for anyone above to hear. He struggles uselessly feeling the freezing snow around his body, closes his eyes, and awaits death.

.

“Grab my hand.”

.

Artist Statement

.

The 2000 Nisga’a Treaty was the first treaty ever signed between an Aboriginal group and the British Columbia government. The Nisga’a gained an independent government with jurisdiction similar to that of other local governments. In addition, the CCC, the Charter, and other laws would apply to the Nisga’a as they do to every Canadian. I chose to write a story based on these events because the treaty was one of a number of cases where First Nations title was proved valid and had never been extinguished. The treaty process was a long battle and I thought that my story needed to shine light on a very important part of First Nations history.

.

Read Trevor Jang’s full story here.

Notay Kiskintamowin "Wanting to Know"

Excerpt

.

DELLA-ROSE

.

I didn’t know I was Native until about 15 years ago…I thought I was Mexican.

.

PIXIE

.

Mexican? You can tell you’re a neech from a mile away…why the hell would you think you were Mexican?

.

DELLA-ROSE

.

Well I found out I was adopted and that I was born in Manitoba when I was about 13. My older sister Bonnie came to Winnipeg for a symphony performance and when she came home she said there were a whole bunch of Mexicans in Winnipeg, and that I looked like them. So I just assumed I was Mexican.

.

Artist Statement

.

Notay Kiskintamowin is about a young woman’s journey of self-discovery and the reclamation of her indigenous identity. I used many factual situations of the Aboriginal Peoples of Turtle Island and some of the realities we have faced in our history. I tied this in with stories I’ve learned over the years from my immediate family and friends.

.

I think this piece of writing was a way for me to vent frustration about the negative societal truths our people endure in a way that stayed true to the humour and perseverance of our people. I am not yet finished this play, I don’t know if I ever will be. As I continue to grow as a person and as a writer, I will continue to go back and add to this story.

.

Read Shaneen Robinson’s full story here.

Three People and a Register

Excerpt

.

The Little Girl

.

A tiny little girl was born in 1985, the year that Aboriginal women won a historic victory against the Canadian government. The Abenaki community of Odanak was the centre of her world. The little girl grew up there, constantly wondering who she was. Neither this, nor that. Who was this person? She was one of those who are called “non-status” — something no one wanted to be. But the little girl had an ally whose strength was underestimated. He was strong and he was proud. Once in the community, he had to overcome the same hardships as the little girl. Both of them knew discrimination.

.

Artist Statement

.

Having faced many challenges, which are very often related to identity, Aboriginal people are resilient. I was inspired to write this piece by my own family history. This story is not unique to my family; other Aboriginal families have lived it as well. My grandfather told me this story many times, but it took me a while to really understand the meaning. Now I would like to tell it to you in my own way. I want to pay homage to my grandfather and my mother by sharing a part of their story with Canadians. Were it not for my mother and grandfather, I would not be the person I am today.

.

Read Suzie O’Bomsawin’s full story here.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom