In 1942, the Canadian federal government forced about 21,000 Japanese Canadians to leave their homes. They lived on the West Coast of British Columbia. They lost almost everything they had. They lost their homes. They lost their cars. They lost their boats. They lost their possessions. They were deported and forced to live in camps in small towns. Most of the towns were in British Columbia. They are often called internment camps. Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to their homes until 1949. Many of them never got their homes or their possessions back. In 1988, the federal government apologized for what it did. It also gave $21,000 to the survivors. This action is called redress. Redress means to right the wrongs of the past.

(This article is a plain-language summary of Internment of Japanese Canadians. If you are interested in reading about this topic in more depth, please see the full-length entry.)

Events Leading Up to Internment

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, most Japanese people in Canada lived in British Columbia. They experienced a lot of discrimination and racism. (See Anti-Asian Racism in Canada.) Many people in British Columbia wanted the province to only have white people. The government of BC made it illegal for the Japanese to vote. Canada did not want much Japanese immigration either. So, in 1907, it started to only allow 400 Japanese men to come to Canada every year. This number went down to 150 in 1928. Women and children could still immigrate.

Anti-Japanese racism became much worse after the Second World War started. It got even worse after 7 December 1941. This was the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. It was also the day Canada went to war with Japan. (See also Canada and the Battle of Hong Kong.) Japanese Canadians were seen as enemies by many Canadians, especially in BC. Some thought they were spies. Many people wanted the government to force the Japanese on the West Coast to leave their homes.

Soon after Pearl Harbor, the government took away Japanese Canadian fishermen’s boats. There was no evidence that they were spies. In fact, the RCMP found no proof that any Japanese Canadians were spies. Yet, the federal government still decided to force Japanese Canadians to leave the coast. Many politicians in BC put much pressure on the federal government to do this. They wanted to imprison Japanese Canadians in camps with guards. (See Internment in Canada.)

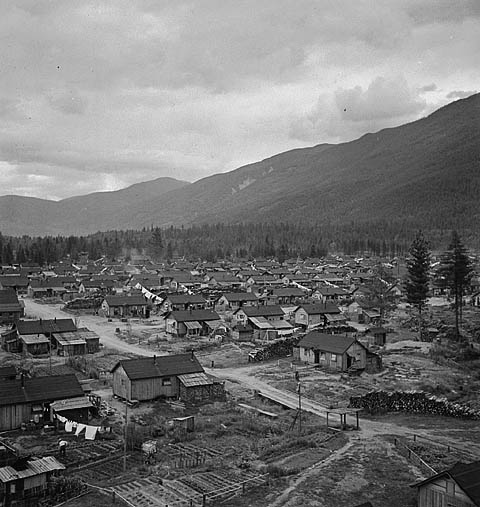

Male Japanese Canadians were the first to be forced to leave their homes. Prime Minister Mackenzie King ordered them to leave in January 1942. Soon after, he made a law that forced all Japanese Canadians living 160 kilometres from the coast to leave. And they did. By the summer of 1942, there were no Japanese Canadians on the coast. Most went to the interior of BC. Some of the towns they lived in were called New Denver, Kaslo and Hope. Over 3,000 Japanese Canadians went to Alberta. Many of them were sent to work on sugar beet farms.

Life was hard in the camps. Many families were crowded into tents or shacks. People were not allowed to bring most of their belongings with them.

After Internment and Legacy

In 1945, the government gave Japanese Canadians the choice to move to Japan or elsewhere in Canada. About 4,000 went to Japan. The Canadian government forced some to do so. (See Deportation from Canada.) In addition to this, most Japanese Canadians ended up losing almost everything. When they returned home in 1949, they learned that their property had been sold. Their houses had been sold at low and unfair prices. In the 1980s, the federal government offered some compensation. In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney gave an apology. These were just the first steps toward healing the wounds of the past.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom