Canada’s longest Second World War army campaign was in Italy. Canadian forces served in the heat, snow and mud of the grinding, nearly two-year Allied battle across Sicily and up the Italian peninsula—prying the country from Germany's grip, at a cost of more than 26,000 Canadian casualties.

|

The Italian Campaign |

|

| Date | 10 July 1943–2 May 1945 |

| Location | Italy |

| Participants |

Allies: included United Kingdom, United States, France, Canada, New Zealand and Poland

Axis: Germany, Italy |

| Canadian Casualties (approximate) |

26,200 in total

5,300 killed 19,400 wounded |

Map of Allied operations in Southern Italy, September 1943 to January 1944

(Map drawn by C.C.J. Bond, in C.P. Stacey, The Canadian Army 1939-1945: An Official Historical Summary (1948), Department of National Defence / transcribed and formatted by Patrick Clancey, HyperWar Foundation

Operation Husky

Canada's Italian campaign started on 10 July, 1943 when the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade began Operation Husky — the seaborne invasion of the island of Sicily. The Italian defenders were quickly overwhelmed and the Canadians advanced on Pachino and its strategic airport. Nightfall saw most of the Canadian units either on or past every initial objective. Seven men died and 25 others were wounded.

On 11 July, the Canadians were delayed, not as much by enemy opposition than by thousands of Italian troops wanting to surrender. The Canadians followed an inland route that guarded the British Eight Army’s left flank up the eastern coastline toward Catania and the ultimate objective of the Strait of Messina, which divides Sicily from the Italian mainland.

With the Italian army’s rapid collapse, several German divisions hurriedly established a series of defensive lines. Canadian troops encountered such a line on 15 July near Grammichele. Enemy anti-tank guns knocked out one tank, three carriers, and several trucks before the Canadians rallied and carried the town. Having inflicted 25 Canadian casualties, the Germans withdrew.

German tactics in Sicily were a precursor for those applied throughout the Italian campaign. This entailed heavily entrenched fortifications set on ideal defensive terrain of ridges, mountains, and rivers. When one line was breached the Germans quickly withdrew to another.

Canada's "Mountain Boys"

On 18 July, the Canadians met their heaviest resistance to date at Valguarnera. Fighting before the town and on adjacent ridges resulted in 145 casualties, including 40 killed. But the Germans lost 250 men captured and an estimated 180 to 240 killed or wounded. Field marshal Albert Kesselring reported that his men were fighting highly trained mountain troops. “They are called ‘Mountain Boys,’ he said, “and probably belong to the 1st Canadian Division.” German respect for the Canadian soldier was beginning.

For the next 17 days, the Canadians were hotly engaged. At Leonforte, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade spent a night of house-to-house fighting. Meanwhile, the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment carried out a nighttime ascent of the 904-metre high Monte Assoro to surprise the German defenders.

By the first week of August, the Germans were caught in a closing vise of American, British, and Canadian units. On 17 August, the Germans evacuated Sicily. By then, the Canadians had marched 210 kilometres and suffered 2,310 casualties, including 562 dead.

Long Mainland March

After a brief rest, the Canadians were placed in the British Eighth Army’s vanguard for the invasion of mainland Italy. A long, arduous march up Italy’s boot began when the West Nova Scotia and Carleton and York regiments of 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade landed immediately north of Reggio Calabria on 3 September.

Again, opposition came mostly in the form of Italian soldiers surrendering by the hundreds. On 8 September, the Italian government itself surrendered to the Allies. In the surrender’s wake, German troops raced to intercept the Allied advance. Southern Italy’s rugged country was ideally suited for defence. It took the Canadians two weeks in October to advance just 40 kilometres from Lucera to Campobasso. This stubborn fighting withdrawal by the Germans bought them time to create a fortified system of defensive lines well south of Rome. Dubbed the Gustav Line, the system hinged on the high point of Monte Cassino in the west and the Sangro River in the east. On 28 November, British troops assaulted the Sangro River. After nearly a week of heavy fighting, the Germans pulled back from this river to a new line behind the Moro River.

Assault on The Gully

Winter rains had turned the landscape into a quagmire. On 6 December, Canadians assaulted the Moro River defences. Only the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry made headway, capturing Villa Rogatti before ordered to withdraw. A firm bridgehead was finally established across the Moro on 9 December, but further advance was blocked by a deep, narrow pass nicknamed The Gully.

Repeated frontal assaults by multiple battalions were cut to pieces. Then on the night of 14-15 December, the Royal 22e Regiment outflanked The Gully. Eighty-one men of Captain Paul Triquet’s ‘C’ Company and seven Ontario Regiment tanks headed for a farmhouse called Casa Berardi. When the company’s dwindling ranks wavered, Triquet shouted, “The safest place for us is the objective.” At 2:30 p.m., Casa Berardi was taken. Triquet became the first Canadian in Italy to win a Victoria Cross for valour. After four more days of fighting to gain a vital crossroads, the Germans withdrew from The Gully into the town of Ortona.

Captain Triquet, ignoring the heavy fire, was everywhere encouraging his men and directing the defence and by using whatever weapons were to hand personally accounted for several of the enemy. This and subsequent attacks were beaten off with heavy losses and Captain Triquet and his small force held out against overwhelming odds until the remainder of the battalion took Casa Berardi and relieved them the next day.

(Excerpt from the Victoria Cross citation for Captain Paul Triquet, London Gazette, no.36408, 6 March 1944)

Ortona

On 20 December, the Loyal Edmonton Regiment and Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, supported by tanks from the Three Rivers Regiment, became embroiled in vicious house-to-house fighting in Ortona with the German 1st Parachute Division. Finding that advancing along the streets was impossible, the Canadians blasted their way through the interlinked walls of the town’s buildings — a technique called mouse holing. There was no pause in the fighting for Christmas Day, but the Seaforth’s quartermaster and headquarters staff organized a sumptuous dinner. One by one, Seaforth companies withdrew to a church on Ortona’s outskirts, were served dinner, and then returned to battle. The Edmontons and most tankers had no such reprieve.

Not until the night of 28 December did the Battle of Ortona end with a German withdrawal. The December fighting cost 2,605 Canadian casualties, including 502 killed. There were also 3,956 evacuations for battle exhaustion and 1,617 for sickness, out of a total Canadian strength at the beginning of December of about 20,000. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division, however, had mauled two German divisions and achieved its objective.

The New Year found an expanded Canadian force facing the Germans across the Arielli River, just north of Ortona. In early November, I Canadian Corps was formed by the addition of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division to Italy. Its baptism of fire, however, came on 17 January 1944 with an attempt to cross the Arielli that was repulsed at a cost of 185 casualties.

Breaking the Gustav Line

Despite local victories, overall Allied attempts to break free of the Gustav Line remained frustrated throughout the winter, leading to a decision to concentrate forces for a joint offensive by the Eighth Army and the US Fifth Army at Monte Cassino. Accordingly, the Canadians moved there in late April.

On 11 May, the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade supported an 8th Indian Division attack. The Calgary Tank Regiment established a tenuous bridgehead across the Gari River that enabled the Indians to break the Gustav Line and open the way — along with breakthroughs by other Allied units — for an advance against the next defensive position, known as the Hitler Line. Like the Gustav Line, this defensive system bristled with pillboxes, tank turrets mounted on concrete emplacements, and vast concentrations of barbed wire and minefields.

Hitler Line

Cracking the Hitler Line fell to I Canadian Corps, which moved toward it on 18 May. Attempting to avoid the heavy casualties inherent in set-piece attacks, the 1st Division’s commander, Major-General Chris Vokes attempted to pierce the line with individual battalion thrusts. When these failed, he implemented Operation Chesterfield, a two-brigade wide assault on 23 May.

The three battalions of 2nd Brigade were shredded by enemy fire on the division’s right flank and suffered 162 men killed, 306 wounded, and 75 taken prisoner — the single highest loss rate suffered by any brigade in a day’s fighting in Italy. To the left, however, the 3rd Brigade’s Carleton & York Regiment pierced the line. The remaining two battalions and the Three Rivers Regiment tanks soon widened this narrow gap to enable the 5th Canadian Armoured Division’s advance past the Hitler Line.

Capture of Rome

The Eighth Army continued up the Liri Valley towards Rome against fierce resistance. The advance stalled briefly at the Melfa River in a costly battle involving the 5th Division’s Westminster Regiment. For leading the successful defence of a small bridgehead across the river, Major Jack Mahony was awarded a Victoria Cross.

The capture of Ceprano on 27 May cracked the German resistance before Rome, and the city was liberated on 4 June. Three weeks of action for I Canadian Corps resulted in about 800 dead, 2,500 wounded, 4,000 sick, and 400 battle exhaustion cases. Meanwhile, attention was shifting to France. When the Allies invaded Normandy on 6 June, Italy became a largely forgotten theatre of war. Derided as D-Day Dodgers, the rank-and-file soldiers fighting in Italy transformed the epithet into a mark of pride.

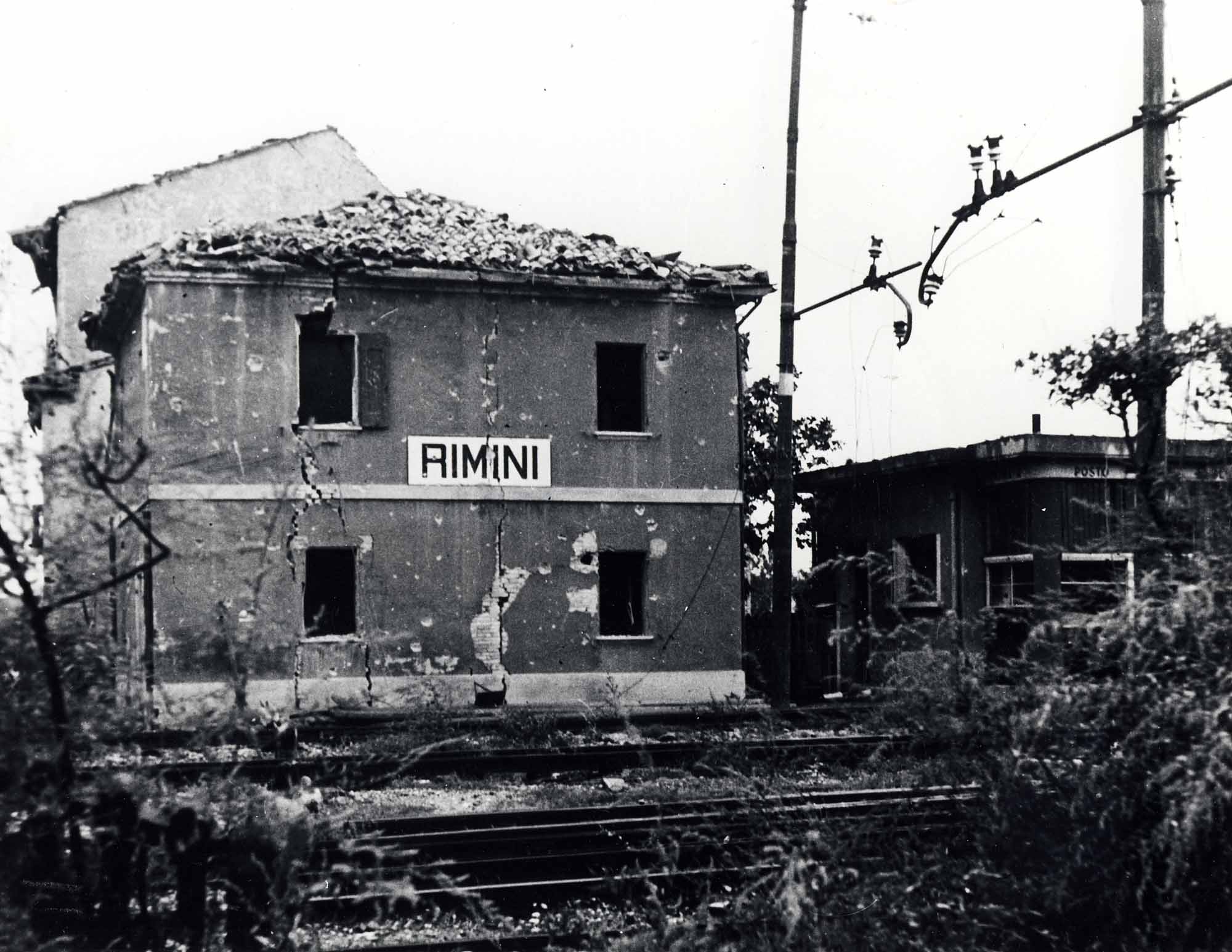

Gothic Line

The Allies marched northward to the Gothic Line in August, which the Canadians were tasked with breaking at Pesaro on the Adriatic coast. Striking on 25 August, the 1st Infantry Division sought to open a breach through which the 5th Armoured Division could pass. Encountering line after line of heavy defences, the Gothic Line was not fully overcome until 21 September, at a cost of 4,511 Canadian casualties that included 1,016 dead — among other Allied losses. It took until 20 October to capture the city of Cesena just 20 kilometres from the next offensive’s starting point. Cesena stood alongside the Savio River, and here the following day, Private Ernest Alvia Smith earned a Victoria Cross by staving off a German armoured column.

After spending November in reserve, the Canadians returned to attack Ravenna. The city fell on 4 December, but heavy fighting raged through the rest of the month with few gains.

After a short stand down, I Canadian Corps started withdrawing from Italy in February 1945 to rejoin the First Canadian Army in northwest Europe. The Italian campaign ended in the spring of 1945, with Germany's eventual surrender. The Canadians who had slogged their way through Italy from south to north since 1943 would not see victory there, participating instead in the liberation of the Netherlands, and the eventual invasion and defeat of Germany itself.

Total Canadian casualties in Italy were 408 officers and 4,991 non-commissioned men killed. A further 1,218 officers and 18,268 men were wounded and 62 officers and 942 men were captured. Another 365 died of other causes. Of the 92,757 Canadians who served in Italy, 26,254 became casualties there.

The regiment, as a whole, had very heavy losses from time to time. We landed in Sicily with 756 men. We wound up in December, approximately 15 December 1944, with - our major had sent a letter, a phone call rather, around “Toons,” telling them of the fact that of 756 men who’d landed in Sicily on 10 July 1943, there were exactly 34 of us left. (Veteran George F. Burrows of the Canadian army, recalling the Battle of Ortona. Click here to listen to Burrows’ interview with The Memory Project.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom