Myrtle Eugenia “Jean” Watts (married name Lawson, a.k.a. Jim Watts), theatre artist, writer, activist (born 5 March 1909 in Streetsville, Ontario; died 23 May 1968 in Saanich, British Columbia). Jean Watts was a theatre director and journalist and an active member of the Communist Party of Canada. During the Spanish Civil War, she worked as a war correspondent as well as an ambulance driver and mechanic for the International Brigades. She was the only woman to join the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion.

Childhood and Education

Myrtle Eugenia Watts, known mostly as Jean (or Jim) Watts, was the younger of two children of Herbert Lanyon Watts and Edna Myrtle Watts (née Corcoran). She had an older brother, Herbert Leonard Watts. Records about her parents are scarce, but evidence suggests that the family’s social and economic status was comfortable: Watts received a considerable inheritance from a wealthy grandfather once she came of age. She was educated at Glen Mawr School for girls in Toronto.

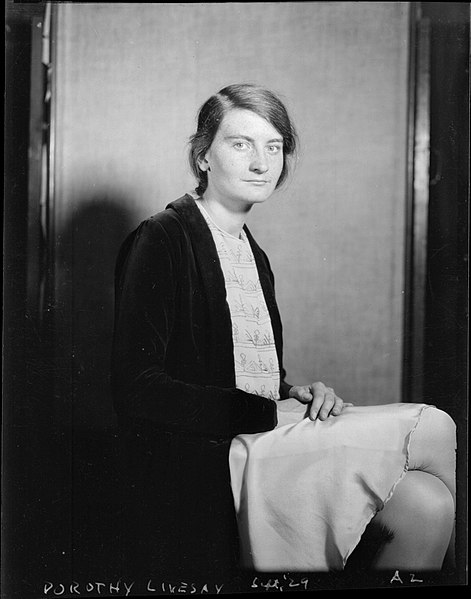

When she was about 12 years old, Watts met and befriended Dorothy Livesay, later one of Canada’s most prominent modernist poets. The two girls were classmates at Glen Mawr, went on to study at the University of Toronto and shared a passion for poetry and literature. Their close friendship would continue throughout their adult lives, and Watts features prominently in Livesay’s writing.

At the University of Toronto, Watts first enrolled in pre-medical school but dropped out after two years because she found the program exhausting. She then took classes in psychology, philosophy, literature and German. During breaks from her academic studies, she traveled to Europe, hiking in Spain or visiting France, Germany, England or Ireland with friends. In the spring of 1933, Watts completed her studies with a degree in psychology.

Early Communist Activism

Even as a teenager, Jean Watts defied the conventions of her middle-class upbringing. She wore masculine clothes, preferred the nickname “Jim” to her given names and read works by playwright and political activist George Bernard Shaw and revolutionary socialist Friedrich Engels. In 1927, she attended a lecture series by anarchist Emma Goldman covering, among others, issues of women’s emancipation and birth control.

As a university student in the winter of 1931–32 Watts joined the Young Communist League and became a member of the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) shortly after. Her radicalization was likely accelerated by the harsh government measures against the CPC and the 1931 arrest and conviction of Tim Buck and other CPC leaders; these events caused a surge in interest, support and membership for the CPC, especially among middle-class urban youth. In the University of Toronto campus groups, Watts met other student activists, notably Stanley Ryerson. During and after her psychology studies, she held leadership positions with the Young Communist League, the Student League of Canada, the party publication The Young Worker and the Progressive Arts Club (PAC).

Workers’ Theatre and Theatre of Action

With her interest in literature and culture, Jean Watts devoted herself to the PAC. She became a leader in its theatre division and founded the Workers’ Experimental Theatre (WET), later known as Workers’ Theatre, in 1932. In 1933, she staged, directed and acted in the WET’s production of Eight Men Speak, an agitprop (propaganda) play coauthored by four senior CPC members. The focus of the production was less on theatrical professionalism than on political activism within a larger CPC campaign for the release of Tim Buck. Eight Men Speak premiered in Toronto on 4 December 1933 and was immediately banned by the prime minister.

On 29 May 1934, Watts married William Thomas (Lon) Lawson, a writer and editor for CPC publications who was also involved with the Workers’ Theatre. Together, they moved to New York in the fall of 1934, where Watts took acting and directing classes at the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre and worked with the Workers’ Laboratory Theatre. She was eager to professionalize her theatrical work and move beyond agitprop toward more sophisticated forms of workers’ theatre. This was in line with a general shift of Communist cultural politics on the international level.

When she returned to Toronto in June 1935, Watts got involved in the new Theatre of Action, successor of the Workers’ Theatre. (The replacement of workers’ theatres with Theatres of Action was part of the shift in Communist cultural politics.) She established a drama school using the Stanislavskian method she had studied in New York. In early 1936, she directed the Theatre of Action’s inaugural performance of Waiting for Lefty, a one-acter by Clifford Odets, which she knew from New York. While the play deals with Communist themes, Watts chose a version without explicit Communist propaganda; however, at the same time, she also directed several agitprop shows with the Theatre of Action, indicating both her continuing interest in revolutionary activism and the desire to appeal to a wider audience.

Anti-fascist Journalism in Canada

Jean Watts began to publish in Communist journals and magazines in her early twenties. While still a student in 1932 or 1933 she became business manager of the Toronto-based monthly magazine The Young Worker (which became biweekly in 1934). She wrote articles, editorials and her own column. As early as 1933, she warned against war in Europe, calling for a united front against fascism. In December 1933, she was arrested for selling the paper in the street.

Watts also wrote for the CPC newspaper Daily Clarion, including a series of articles in the winter of 1935–36 discussing Soviet theatre and plays she had seen during a trip to Moscow. In the spring of 1936, she joined her husband William Lawson in launching a new Communist literary journal, New Frontier. She used her inheritance money to finance it.

During the spring of 1936, Watts’ focus within the Communist cause shifted from theatre to the situation in Spain, where the elected left-wing Republican government was threatened by a coup from the Nationalist right, backed by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. In late summer 1936, Watts resigned from the directorship of the Theatre of Action and joined the Communist International’s campaign for the Spanish Republic.

Journalism in the Spanish Civil War

In February 1937, Jean Watts traveled to Spain as a war correspondent for the Daily Clarion, despite her wish to join the International Brigades. She was posted to Madrid to report on the Blood Transfusion Institute established by Norman Bethune. The Daily Clarion advertised her prominently as “girl reporter” and “probably the only Canadian girl gathering news in Spain.” Her role was also unique (along with Ted Allan, who likewise reported for the Daily Clarion from Spain) in that no other Canadian newspaper assigned correspondents exclusively to coverage of the Civil War.

Watts functioned as a “public relations person” (as she later described it) for the Blood Transfusion Institute but was at liberty to cover other topics as well. In addition to reporting on the Institute’s medical care, she covered behind-the-front issues such as the lives and suffering of civilians, the immediate impact of bombings in Madrid and the preservation of cultural artifacts. She also made radio broadcasts and assisted in the daily operations of the Blood Transfusion Institute. However, she did not appreciate being restricted to Madrid and left the Institute in June 1937 for a short-term job at the Republican Government’s censorship office in Valencia.

Work with the International Brigades

In the fall of 1937, Jean Watts succeeded in joining the International Brigades by applying as a driver. She enlisted in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the Canadian section of the Brigades, as the only woman to do so. Watts was assigned to a British medical unit as an ambulance driver and mechanic. Known to her fellow drivers as Jim, she was comfortable within the exclusively male environment.

In January 1938, Watts returned to Canada but continued to support the Battalion and Republican Spain. She traveled the country to give speeches, held recruitment rallies for the Battalion and, when the Republican forces lost the war in the spring of 1939, raised money for veterans and Spanish refugees. She also traveled to Paris in April 1939 to attend a refugee aid conference and visit refugee camps, and she reported on both for the Daily Clarion.

Later Years and Death

During the Second World War, the CPC was banned, and Jean Watts could no longer work on its behalf in public. She initially joined her husband, William Lawson, in underground work for the party, but in December 1941 she enlisted in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, working within Canada as a driver and personnel officer. By 1946, when the Corps disbanded, she had risen to the rank of lieutenant. After the war, she settled with Lawson in Prince Edward County; by 1948 the couple had adopted a child.

Few records exist for Watts’ later life. She moved to Saanich, British Columbia, with Lawson in or after 1951. Although she no longer published or campaigned, she remained committed to progressive ideas and antiwar activism. In 1966 she founded the Victoria, BC, branch of the Voice of Women for Peace. On 23 May 1968, she died by suicide in Saanich.

Legacy

In her memoir, Dorothy Livesay described her friend Eugenia “Jean” Watts as “the New Woman;” this term generally refers to women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who challenged traditional expectations and roles and promoted women’s suffrage, educational opportunities, sexual independence and “rational” or masculine dress.

Watts was certainly a pioneer: she was one of the first female war correspondents, paving the way (along with her fellow Spanish Civil War correspondent, American Martha Gellhorn) for Second World War journalists such as Helen Kirkpatrick and Ruth Cowan. Although married, she pursued an ambitious and independent career, using her birth name Watts throughout her professional life.

Like other “new women,” she sometimes wore masculine clothes and used a male or gender-neutral first name (Jim or “J.”) rather than her given name. In her letters to Livesay, she identifies as bisexual. As a university student, she had relationships with women and men; among the latter were Otto Van der Sprenkel, a budding political scientist who deepened her interest in socialism and Marxism, and Stanley Ryerson. According to historian Nancy Butler, Watts remained “bisexual and non-monogamous” throughout her long marriage with William Lawson.

What is known about Watts today is largely based on Dorothy Livesay’s writing. But Livesay’s account is often subjective and warrants complementary study. Watts’ role within the Communist movement in the early 1930s and her journalism in the mid-1930s have yet to be fully acknowledged by historians. However, since her death, Watts has sparked some interest in the Canadian theatre scene; a 2010 play by Tara Beagan (Jesus Chrysler) and a 2024 play by Beverley Cooper (Jim Watts: Girl Reporter) are based on Watts’ life.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom