Childhood and Education

Jeanne Corbin was born in March 1906 in the village of Cellettes in the department of Loir-et-Cher, France, where her parents, Jean-Baptiste Corbin and Henriette Marguerite Louise Valpré, owned a small vineyard. But in 1911, after two years of bad weather, floods and very poor harvests, the Corbin family decided to leave France and settle in Canada. They boarded the Lake Erie in Le Havre on 1 April 1912, landed in Saint John, New Brunswick 11 days later, and then took the train to Lacombe, Alberta. From there, the family headed to Lindbrook, 10 km from the village of Tofield, northeast of Edmonton, where they were granted 160 acres of land.

For reasons that are unclear, Jeanne Corbin did not begin attending the small English-language primary school in Lindbrook until 1917, when she was 11 years old. The school had only 10 students in grades 1 through 6. In April 1921, Jeanne completed Grade 6. Her parents then sent her to live in a boarding house in Edmonton while she attended Westmount High School. She transferred to Victoria High School in 1924 and received her Grade 12 diploma in June 1926, at the age of 20.

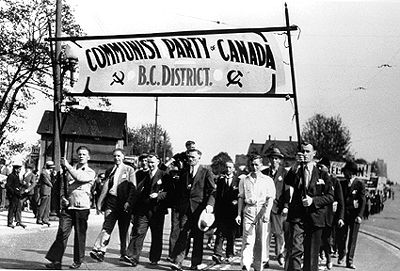

Early Years with the Communist Party of Canada

Jeanne Corbin attended meetings of the Young Communist League of Canada, and she joined the Communist Party of Canada when she was 18. Edmonton was fertile ground for the party’s efforts. The city had a large population of Ukrainian origin and leftist groups working together within the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association. While attending Victoria High School, Corbin worked with the Young Pioneers, a group for children whose parents were members of trade unions or of the Communist Party. She also sold subscriptions to the Communist newspaper The Worker, published in Toronto. On 29 November 1925, after Corbin met with a group of young pioneers, RCMP Superintendent Jos. Ritchie opened a file on her, describing her as a “dangerous Communist Agitator”.

In September 1926, with the goal of becoming a teacher, Corbin enrolled in the normal school in Camrose, south of Edmonton, and received her teaching certificate at the end of the school year. In summer 1927, she worked as an assistant to the director of the Sylvan Lake Camp in central Alberta, a Communist summer school that offered various courses to vacationing workers. At the end of the summer, despite RCMP efforts to prevent this Communist militant from teaching at any school in the province, Corbin was hired to teach at the school in Smoky Lake, north of Tofield. But in September 1928 she was fired for having openly taught socialism in her classroom. She returned to Edmonton and worked at the Labour News Stand, a leftist bookstore. In summer 1929, she worked organizing jobless women in Edmonton and fighting the prospect of war with the USSR.

In fall 1929, Corbin left Edmonton for Toronto to work with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Canada. Upon arriving, she became secretary of the Canadian Labour Defense League, which defended the rights of workers arrested during strikes and demonstrations, regardless of their political or union affiliation, race, colour or nationality. She herself was arrested on 19 October 1929 while leading a demonstration at Queen’s Park, but was released after paying a $1000 fine. Judge Margaret Patterson eventually sentenced Corbin to 30 days in prison. After having served two-thirds of this sentence at the Women’s Industrial Farm in Concord, Ontario, she was released by order of the court.

In 1930, while continuing her work for the Canadian Labour Defense League, Corbin also became business agent for the Communist Party newspaper The Worker, replacing activist Beckie Buhay in this capacity At the party leaders’ request, Corbin toured Canada promoting this newspaper, but the Great Depression was on, which made her task difficult. Jobless workers had no money to buy newspapers, and after several weeks of touring, she had garnered only $126 worth of new subscriptions, $131.50 in renewals and $148.68 in donations. While on the road, she also helped to establish a French-speaking section of the Communist Party in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba.

Organizing for the Communist Party’s Second District in Montreal

In 1930, in recognition of her past work, the party appointed Jeanne Corbin as organizer for its Second District in Montreal. Her chief tasks were to persuade French Canadians to join the party and to support her fellow French-speaking party members, who were few in number. For two years, she played several roles, union organizing prominent among them. In February 1931, alongside Edmond Simard, Fred Rose, Don Chalmers, Tom Miller and the Young Communist League, she went to Cowansville, Quebec to lead a textile workers’ strike at the Bruck Silk Mills. There she applied her union-organizing talents to help the strikers, who had walked out after their employer had imposed a 25 per cent pay cut. But Corbin did most of her union organizing in Montreal. There she strived against great odds to organize female workers in the needle trades, although the Second District’s lack of staff and funding and made it hard for her to be effective. The Great Depression also made it very hard to mobilize workers in this industry.

During her years in Montreal, Corbin also translated and distributed tracts and brochures for the Communist Party while continuing her efforts for The Worker. In April 1931, she became editor of the French-language newspaper L’Ouvrier canadien, for which she also wrote some articles under the pseudonym Jeanne Harvey. This paper had experienced financial difficulties before, and Corbin was attempting to get it back on its feet, but after publishing five more issues, it ceased publication in October 1931.

Working in Timmins and Abitibi

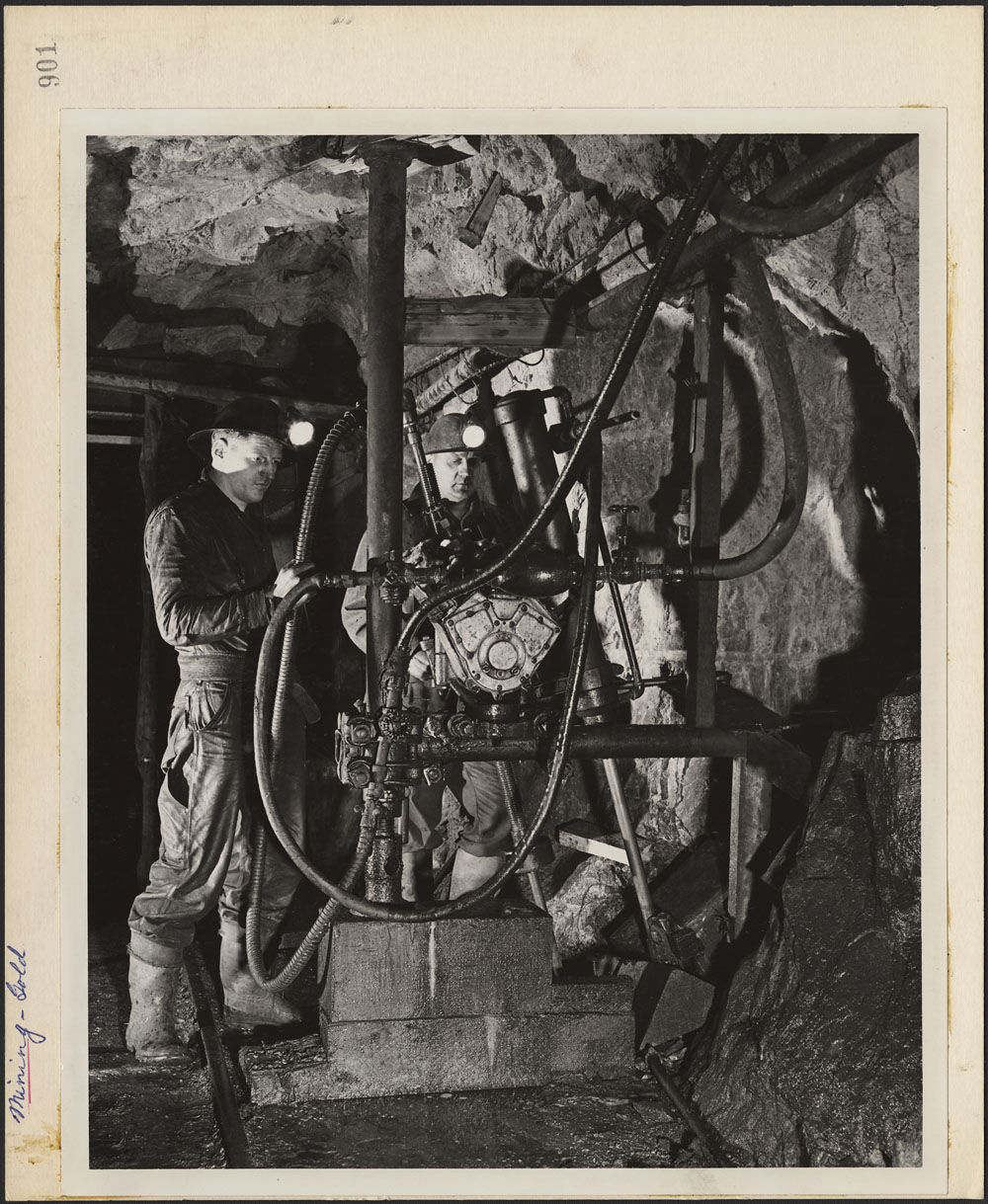

In 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Canada asked Corbin to return to Toronto, then sent her to Timmins, in northern Ontario, to serve as secretary for the Canadian Labour Defense League. The area was fertile soil for the party, because northern Ontario and the adjacent Abitibi region of Quebec were then the site of various struggles by industrial trade unions in a mining- and forestry-based economy whose workers came from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds (French, English, Finnish, Ukrainian and Polish) and spoke a variety of languages. As a francophone who had grown up among European immigrants in western Canada, Corbin was the ideal candidate for this job, which she held for 10 years. As one of the few francophones in the party, she provided invaluable services by organizing the French-speaking mining and forestry workers of northern Ontario and Abitibi.

In December 1933, Corbin supported the lumber workers’ strike against the Canadian International Paper Company in Rouyn, Quebec (part of the Abitibi region). The police arrested her on 11 December 1933 for a speech at the Ukrainian Labour Temple in which they said she had provoked, excited and counselled the lumber workers to attend an unlawful assembly the following day. Judge Tardif found her guilty and sentenced her to pay a fine of $1,000. On 13 December, she was charged with having fomented the riot that broke out at this event, and she was required to pay another fine, of $2,500 dollars. The Canadian Labour Defense League paid both fines. Corbin was released pending trial and continued her work for the ensuing year. Her trial was held on 1 December 1934, and she was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, which she served at the Ville-Marie Prison in Abitibi.

When released from prison, Corbin returned to Timmins, where she continued her work with the party as secretary of the Canadian Labour Defense League for the Fourth District. Starting in 1937, she served as secretary to the manager of the Workers’ Cooperative in Timmins and lived on the second floor above its store. Her duties included supplies, inventory and purchasing.

In September 1939, her health deteriorating, Corbin consulted a physician, who found no cause for concern. But she was suffering from abdominal pains, migraines and nosebleeds, and a number of her woman friends in the Party, including Annie Buller, Beckie Buhay, Isobel Ewen and Helen Burpee, feared the worst. Corbin had probably already contracted tuberculosis at this time. In November 1942, she was hospitalized at the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in London, Ontario and found to have tuberculosis in both lungs. For 18 months, she fought the disease while continuing to keep abreast of current politics, reading many newspapers and magazines and listening to the radio. She received visits from a few friends and corresponded with her closest comrades.

Corbin died in her room at the sanatorium on 7 May 1944, with her nurse in attendance. She was buried in Park Lawn Cemetery in Toronto. Some 50 people attended her funeral, including Communist stalwarts Tim Buck and Annie Buller. Only a number, 4427, etched on a small stone, marks her grave.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom