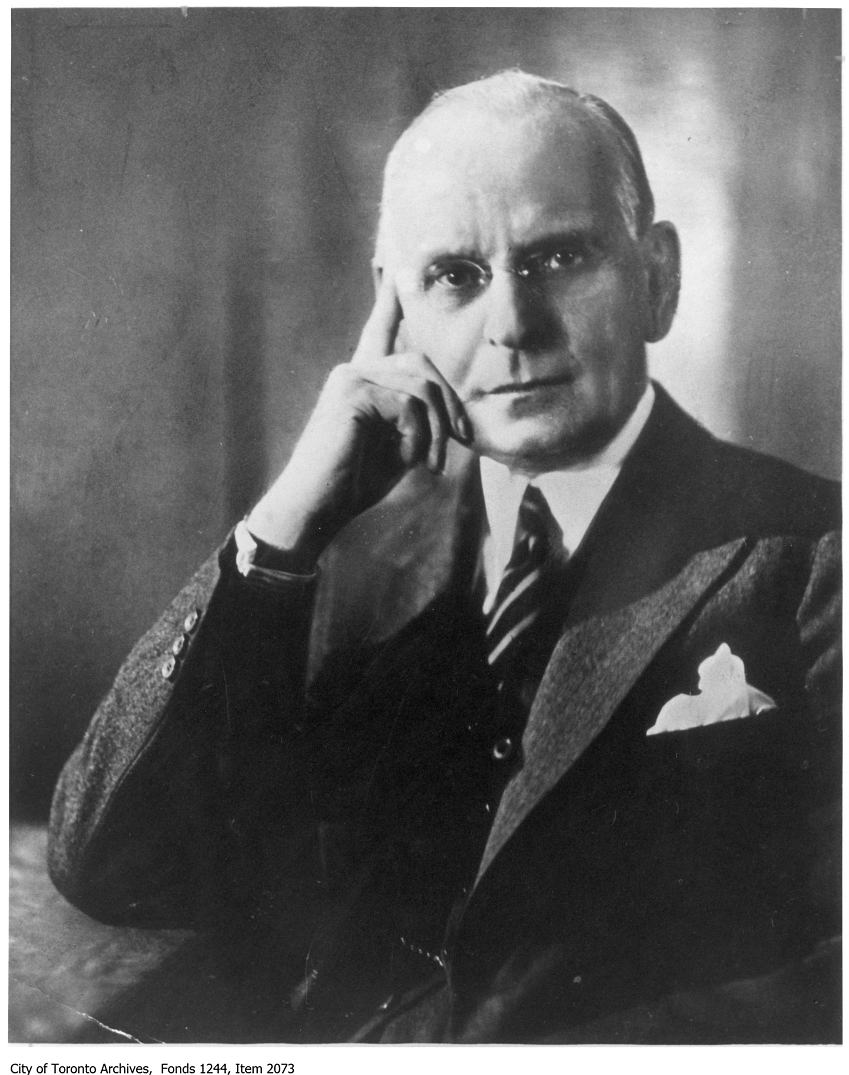

Joseph Atkinson, publisher, journalist, philanthropist (born 23 December 1865 near Newcastle, ON; died 8 May 1948 in Toronto, ON). Atkinson was editor and, later, publisher and owner of the Toronto Star newspaper from 1899 to 1948. Under his direction, the Star became one of Canada’s most influential newspapers and a platform to discuss social legislation in Canada.

Early Years

Joseph Atkinson was the youngest of eight children. His mother, Hannah Atkinson, was widowed when he was six months old. To support her family, she operated a boarding house, where the young Atkinson was exposed to the effects of poverty. He adopted “E” as a middle initial during a teenage stint as a post office clerk.

Early Journalism Career

At the age of 18, Joseph Atkinson took a job at the Port Hope Times collecting outstanding debts. With publisher J.B. Trayes increasingly preoccupied with a political career, Atkinson’s responsibilities grew to include office management, reporting and editorial writing. Atkinson was offered an opportunity to buy the Times by its creditors at the age of 20, but he refused. After he was denied a raise, Atkinson left the Times for a job as a reporter at the Toronto World in 1888.

Atkinson moved to the Toronto Globe in 1889, covering the Ontario legislature for two years before switching to the federal parliamentary beat. Atkinson’s views grew closer to the Liberal Party, forming an alliance that lasted the rest of his career. In 1892, he married writer Elmina Elliott, who worked for the Globe’s women’s page under the pen name Madge Merton. (See also Newspapers in Canada:1800s-1900s; Globe and Mail.)

Joining the Star

Joseph Atkinson became managing editor of the Montreal Herald in 1897 but suffered editorial interference. While considering an offer to join the Conservative-leaning Montreal Star in 1899, he consulted his former editor at the Globe, John Willison. He suggested that Atkinson join the struggling Toronto Evening Star, which was about to be sold to a group of prominent Toronto Liberals (see Toronto Star). Atkinson provided a series of conditions, including salary and stock options that would allow him to assume majority control in the future and freedom from political interference from Liberal Party officials. In a series of letters exchanged with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier in 1899, Atkinson defended editorial independence, observing that “a newspaper is a good ally but soon becomes useless as the subservient organ of a party.” Atkinson’s conditions were accepted and, once the sale was finalized, he was officially hired as editor and manager in December 1899.

Building the Star

When Joseph Atkinson assumed his duties, the Star had the lowest circulation among Toronto’s six dailies, hovering around 7,000 copies a day. By 1903, the paper rose ahead of the Daily Mail and Empire, News and World. (See also Newspapers in Canada: 1900-1990s.) By 1909, it had the highest circulation in Toronto and was only surpassed nationally by La Presse and the Montreal Star.

According to Atkinson’s biographer, Ross Harkness, the secret of the Star’s rapid ascent was the rapport it developed with its readership. Harkness surmised in Atkinson’s 1963 biography that “[the Star] reflected the hopes, the yearnings, and the aspirations of the common man. It reported the events that affected his life in language he understood.” While most of the city’s press courted the dominant conservative Protestant culture, Atkinson made the Star into the voice of Toronto’s minorities. In a speech at the University of Toronto in 1901, Atkinson declared that “the paper which is most human will in the end be found to have the most influence.”

Atkinson’s Methodist faith informed his beliefs, ranging from supporting the censorship of morally dubious cultural works to promoting temperance. These beliefs, and the stridency with which he pursued them in the Star’s pages, earned Atkinson the nickname “Holy Joe.”

Among Atkinson’s longest-lasting achievements during his first decade at the Star was the establishment of two charitable funds to alleviate childhood poverty, growing out of his family’s early financial struggles. The Toronto Star Fresh Air Fund, established in 1901, provided children with the opportunity to enjoy time away from Toronto’s oppressive summertime conditions by spending time at camps, farms and other locations that provided healthier air, food and water. Five years later, Atkinson established the Toronto Star Santa Claus Fund to provide Christmas presents for the destitute.

Atkinson worked to shape Liberal Party policy to align with his personal beliefs and causes he promoted in the pages of the Star. In January 1916, he chaired a party advisory committee to study health legislation and social reform, recommending measures such as minimum wage, old-age pensions, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation, which would influence the party platform during its 1919 leadership convention (see Health Policy; Employment Insurance;). He briefly broke with the Liberals in 1917 over conscription and supported Robert Borden’s Unionist government in that year’s federal election.

After the First World War

In the years following the First World War, Joseph Atkinson steered the paper further to the left, showing support for the Winnipeg General Strike and engaging in less “red-baiting” than his rivals. He also supported the creation of institutions such as a provincial hydro utility, the Toronto Transportation Commission and the United Church of Canada. Social reforms were pushed throughout the paper, reflecting Atkinson’s belief that every page should reflect the Star’s philosophy of supporting underdogs and the underprivileged.

Assisted by his son-in-law, Harry C. Hindmarsh, Atkinson poured money into reporting, using any means possible to score stories (see Journalism). The Toronto Star Weekly emerged as a successful stand-alone weekend publication. Among Atkinson’s few financial failures was a brief ownership of the London Advertiser during the mid-1920s, which failed to hurt the Conservative-leaning London Free Press.

Over time, the philosophies that guided the Star became known as the Atkinson Principles. They are usually summarized as support for a strong united and independent Canada, social justice, individual and civil liberties, community and civic engagement, the rights of working people and the necessary role of government. (See also Working-Class History)

During the 1930s, Atkinson shared federal Liberal leader William Lyon Mackenzie King’s concerns about Ontario premier Mitchell Hepburn and his opposition to the welfare state. Atkinson stepped in to help dictate the terms that settled the strike at General Motors in Oshawa in 1937 (see Oshawa Strike). During the Second World War, Atkinson convinced King to introduce family allowances, resulting in their introduction during 1944’s throne speech. The war also saw Atkinson’s feuds with Ontario Progressive Conservative leader George Drew and Globe and Mail publisher George McCullagh deepen, including an unsuccessful libel suit against the rival paper in 1941 (see Conservative Party).

Death

Joseph Atkinson died at home in Forest Hill (amalgamated into Toronto in 1967) on May 8, 1948. He willed the Star to the Atkinson Charitable Foundation, whose profits he intended to distribute as philanthropic gifts to organizations that promoted economic and social reforms. The will was contested by his political and professional enemies to force the sale of the Star, which ultimately led to the purchase of the paper by its trustees a decade later.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom