Judie Barbara Alimonti, immunologist (born 13 March 1960 in Kelowna, BC; died 26 December 2017 in Ottawa, ON). Alimonti made a significant contribution to one of Canada’s greatest achievements in medical science and public health, the development of the Ebola vaccine. (See also Medical Research.) From 2010 to 2015, Alimonti managed the Ebola vaccine during a time when research was underfunded. Alimonti received little recognition for her work during her lifetime, and her colleagues have called her the unsung hero of the Ebola vaccine story.

Early Life and Education

Judie Barbara Alimonti was the third of four children born to Dominico (Nick) and Sheila Alimonti. She attended Kelowna Secondary School where she was involved in numerous extracurricular activities, including field hockey, soccer, basketball and jazz band. Her love for sports would continue into adulthood with participation in field hockey and soccer in women’s recreational leagues. Following her high school graduation in 1978, Alimonti attended the Canadian College of Massage and Hydrotherapy in Sutton, Ontario, graduating in 1981. There she met her husband, Alan Giesbrecht.

Alimonti and Giesbrecht returned to Kelowna, where for the next few years they operated a clinic as registered massage therapists. However, when her mother died prematurely from cancer, Alimonti reportedly wanted to make a contribution to society that would make an important difference to peoples’ lives. While she was still engaged as a massage therapist, Alimonti took some science courses. She then enrolled as a full-time mature student at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, earning a Bachelor of Science in Microbiology in 1991. She studied immunology at the University of Manitoba and in 1998 completed a thesis that is now held by Library and Archives Canada. Alimonti completed her PhD in microbiology at the University of British Columbia.

Cancer and HIV/AIDS Research

Alimonti’s PhD thesis, “Utilizing the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) to enhance immune responsiveness to cancers and viruses” became the basis for an article published in 2000 in the journal Nature Biotechnology. Data from the article was subsequently used in research for a potential breast cancer vaccine. (See also Breast Cancer Research in Canada.)

After graduation, Alimonti worked in Winnipeg as a cancer researcher for CancerCare Manitoba, a provincially mandated agency. She also studied HIV/AIDS with the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Medicine (now known as the College of Medicine).

Ebola Virus Disease — Background

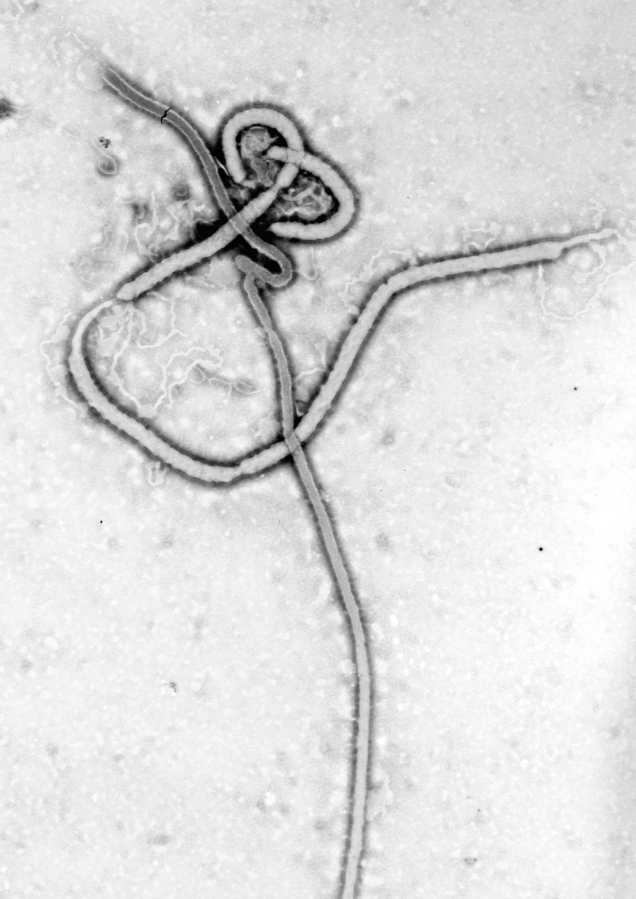

Ebola virus disease (EVD), also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever and generally called Ebola, affects primates, including humans, and other animals (see Virus). Ebola is highly contagious and it is spread through contact with bodily fluids. It is fatal, on average, to about 50 per cent of those infected.

The first case of the Ebola virus was detected in 1976 in the vicinity of the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Outbreaks with high death rates continued sporadically for several decades. In 1999, Canada’s new National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) — part of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) — in Winnipeg began to study the virus and its severity under strict high-level containment conditions. But, as Dr. Francis Plummer of the PHAC and Dr. Steven M. Jones wrote in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (2017), “It took several years to convince funding agencies of the value of spending the National Microbiology Laboratory’s limited resources on Ebola vaccine research over other pressing public health issues in Canada.” Due to that lack of funding, and the fact that lead researchers at the NML were leaving for positions at other research facilities, the Ebola project was at risk of being shelved.(See also Medical Research.)

Dr. Alimonti and the Ebola Vaccine

Judie Alimonti began working for the PHAC as a contract scientist in 2005. She volunteered to take over the Ebola file and between 2010 and 2015 she was the project lead for the Ebola vaccine. Alimonti focused on developing a vaccine that would be of a high enough quality to be rated GMP (good manufacturing processes). The work was laborious and tedious, but she was dedicated to the cause. Because she was employed from contract to contract, her position was always precarious, but she was committed to the project and even turned down an offer for a full-time job because it was not consistent with the level of work she’d been doing.

Skunk Works Operation

While working on the Ebola vaccine, Judie Alimonti set up what is popularly known as a Skunk Works operation — an innovative procedure involving a small group of people working outside the normal research and development channels within an organization. She was involved in every decision regarding the project. Among various tasks, Alimonti developed tests to show that materials shipped to a vaccine manufacturer did not contain microorganisms that would inadvertently contaminate the product. She would later run tests to ensure that vaccines shipped back to her by the manufacturer were free of pathogens. In a 2020 article by STAT, Dr. Frank Plummer, scientific director of the NML from 2000 to 2014, described Alimonti as “a very meticulous, methodical scientist.” In the same article, Dr. Gary Kobinger, head of the special pathogens unit at the NML, said that were it not for the dedication of Alimonti, who he said “put all her heart into it” and would work late at night and on weekends, the Ebola vaccine probably would never have been tested and licensed.

Ebola Epidemics

In 2014, an Ebola epidemic broke out in West Africa. The virus would cause 11,325 deaths by the end of 2016. In response to the outbreak, Canada donated vials of the Ebola vaccine that Alimonti had been working on to the World Health Organization (WHO). Before the donated vaccine could be used, it had to pass clinical trials. (See also Epidemiology.) The vaccine was found to be effective during clinical trials and a vaccination campaign resulted in thousands of lives being saved. Alimonti organized the global distribution of the vaccine to partners during clinical trials.

When there was another outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018, the vaccine was approved for use in that country and more than 260,000 people were vaccinated. In 2019, the vaccine was approved for use in Europe, and in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Later Career and Death

Following her work on the Ebola vaccine, Judie Alimonti was recruited in 2015 by the Human Health Therapeutics (HHT) Research Centre of the National Research Council of Canada in Ottawa. She conducted research on a vaccine for the Zika virus, and although she and her colleagues made progress on that project, she was unable to continue due to illness. After Alimonti’s death from cancer, Alan Giesbrecht stated in a 2018 article by the Ottawa Citizen that, “My wife put her heart and soul into this (Ebola vaccine) and worked day and night to the highest global standards. She could have used more support.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom