Medical Research

Medical research ranges from fundamental research to clinical and applied technology. Fundamental research involves investigations into biological functions; knowledge thus acquired may then be applied in clinical research to help understand specific diseases and to develop improved treatments, cures and methods of prevention. Applied technologies result from both fundamental and clinical research in the form of vaccines, drugs, instrumentation, diagnostics, prostheses and other health-care products. Physicians, biologists, biochemists, biomedical engineers, chemists, dentists, veterinarians, health economists, nurses, and pharmacists are among the health professionals involved in medical research. The overall objective is the improved diagnosis, treatment, prevention and cure of disease and the delivery of health care to Canadians in the most efficient and economical manner.

The discovery of INSULIN in 1922 by Frederick BANTING, J.J.R. MACLEOD, Charles BEST and James COLLIP stands as the most celebrated event in Canadian medical research history. Its discovery led to the establishment of the SANOFI PASTEUR laboratories (formerly Connaught Laboratories) and the Banting Institute at the University of Toronto.

Since that time, research in Canada has been conducted into areas such as molecular biology, neuroscience, immunology, nutrition and metabolism, biochemistry, reproductive biology, CANCER, behavioural sciences, genetics, cardiology, developmental biology, DENTISTRY, microbiology, pharmacology, OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE, health-care organization, environmental health hazards, and the biology and health of human populations.

Canadian investigators, many of whom are world leaders in their areas, are examining the function and diseases of particular organs and systems such as the skin (dermatology), the blood system (hematology), the kidney (nephrology), the eye (ophthalmology), the ear, nose and throat (otolaryngology), the stomach and intestines (gastroenterology), the endocrine glands (endocrinology), the respiratory system (respirology) and connective tissue disorders.

Current Canadian medical research is addressing a number of key health concerns that range from vaccination to surviving cancer. Microbiologists are developing a new meningitis vaccine through innovative genetic research on mouse animal models that could improve the efficacy of vaccination. Because meningitis symptoms progress rapidly a key issue around vaccination is development of a vaccine that can stop the virus before it infects the patient. Oncologists examine the consequences of surviving cancer treatment on patients. Due to the effects of chemotherapy some people are at greater risk of developing other severe health problems such as heart disease, and tailoring survival strategies by following young cancer patients over the long term will help to improve their chances for a healthy life. Sleep researchers are investigating the connection between a sedentary lifestyle, fluid retention and the development of obstructive sleep apnea. The severity of apnea appears related to the amount of daily sedentary activity a patient engages in, such as sitting. This research could lead to addressing the cause of apnea through a healthier lifestyle, instead of merely treating the symptoms.

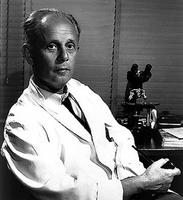

The range of accomplishments is impressive. Research in cardiovascular surgery alone has contributed significantly to the overall treatment of blood vessel and HEART DISEASE. Canadians have been responsible for major developments in heart pacemakers, heart-lung machines to oxygenate blood and correct heart defects, and the first coronary care units. Hans SELYE was a world-renowned expert in understanding STRESS, its effects and its management.

International diabetes research was significantly advanced by a group of researchers at the University of Alberta. Led by Dr. James Shapiro, the team developed an innovative technique to transplant pancreatic islet cells into people whose own islet cells had been destroyed by type 1 DIABETES. The technique, called the Edmonton Protocol, has been available for more than 10 years and has treated more than 100 people. The research allowed the patients to live without requiring daily supplemental insulin and significantly advanced the medical knowledge about diabetes and the ultimate potential of genetic research.

In the neurosciences Canadians have made major contributions to the knowledge of the central nervous system and its related diseases. The Montreal Neurological Institute (established in 1934) is an important centre for such research. Its founder, Wilder PENFIELD, not only pioneered the technique of brain-mapping, which is conducive to the better understanding of localized functions of the brain, but also built the MNI into an internationally known training centre.

Research at the MNI has led to improved surgical and nursing techniques for the management of spinal lesions, to the development of electroencephalography (EEG) to treat conditions such as epilepsy, and to a deeper understanding of cognitive and other behavioural changes associated with brain lesions. Noninvasive imaging techniques, such as computerized axial tomography (CAT) and positron emission tomography (PET), in conjunction with a new understanding of neurotransmitters, help researchers understand the way the various parts of the brain and nervous system grow, develop, take on specific tasks, and repair and replenish themselves.

At the University of Western Ontario, Charles Drake has achieved international recognition for developing new techniques for the improved repair and treatment of potentially fatal aneurysms - weakening or ruptures of brain arteries, notably the basilar artery.

The federal government, provincial governments, voluntary agencies and private foundations, industry, business and foreign sources all contribute to the support of biomedical research in Canada, including equipment, operating costs, research training and technical assistance.

Federal Funding Agencies

The CANADIAN INSTITUTES OF HEALTH RESEARCH (CIHR) is the major federal agency responsible for funding health research in Canada. Established by Act of Parliament in April 2000, it consists of 13 institutes that provide partners in the research process. The CIHR was designed to have a comprehensive mandate and the research partners include the funding agencies, researchers and the research institutes. Each health institute has a broad and inclusive focus and sets priorities for research in each topic area. The institutes are led by an advisory board and scientific director as well as the CIHR governing council. The areas covered by the institutes include: Aboriginal people's health, AGING, cancer, circulatory and respiratory health, GENETICS, health services and policy research, infection, musculoskeletal health, diabetes and PUBLIC HEALTH.

The CIHR was developed out of the Medical Research Council of Canada, part of the NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL. The Medical Research Council began as the Associate Committee of Medical Research in 1936, becoming the NRC Division of Medical Research in 1956 and then an autonomous body of NRC in 1960.

The CIHR funds health research and research training in universities, health-care institutions and research institutes. It provides support, on the basis of scientific excellence as determined by national peer review, for research and for training of health-science researchers in the health-science faculties. These include the departments and laboratories of the 17 medical schools, 10 dental schools and 10 pharmacy schools and their affiliated HOSPITALS and institutes across the country.

Health research at CIHR is divided into 4 broad categories: bio-medical; clinical; health services; and social, cultural, environmental and population health research. The CIHR is also responsible for ensuring that the knowledge generated out of health research is translated into findings that reach decision makers, and therefore help to ensure that medical research ultimately works to benefit the health of Canadians.

The CIHR is also mandated to provide researchers with opportunities to participate in international medical research. It cooperates with the CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (CIDA), the International Development Research Centre and HEALTH CANADA in research to improve people's health in Canada and the world.

Research into cancer is led by the Institute of Cancer Research, with the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control (CSCC) responsible for coordinating all cancer research in the country. The CSCC was created in 1999 and involved the establishment of a research alliance from the groups that were formerly in charge of cancer research - the National Cancer Institute of Canada, the Canadian Association of Provincial Cancer Agencies and Health Canada.

The former major Canadian health research initiatives have largely been maintained and expanded on by the CIHR. Canadian research in genetics is now undertaken by the Institute of Genetics encompassing the work of the former Canadian Genome Analysis and Technology program, which was Canada's participation in the international Human Genome Project. CIHR has research initiatives focused on hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS, antimicrobial resistance, and pandemic H1N1 influenza, among others.

Provincial Funding Agencies

Provincial agencies in Alberta, BC, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec and Saskatchewan contribute to medical research and training through such organizations as the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research and le Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Voluntary Funding Agencies

Voluntary agencies, which are generally "disease-specific," also play a major role in medical research. The National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Canadian Cancer Society integrated in 2009 and created the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI). The CCSRI ensures that cancer research donations fund the most promising Canadian cancer research.

Research costs such as salary support and capital expenses to construct laboratories and animal-care facilities are generally paid by the institutions where the research is conducted. The institutions receive funds for this purpose through provincial governments and private donations.

Structure of Medical Research

Medical research is highly decentralized in universities and teaching hospitals and their affiliated institutions throughout the provinces. Canada is one of a small minority of countries without significant government laboratories devoted to biomedical research. While this decentralization links research with professional training and health-care delivery, it makes it difficult to define or maintain a national focus for concerted programs, especially as health care and education are provincial responsibilities. However, in 1982 federal and provincial representatives identified several health areas of national concern (cancer, accidents, arthritis and joint disorders, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, maternal and infant health problems, MENTAL HEALTH and respiratory diseases).

In 1983, the federal Cabinet approved a framework for medical research that emphasizes the provision of high-quality training; a balance between basic and applied research, and a balance across regions and disciplines (with special attention to areas of national health concern); and the utilization of new knowledge for improved health care. In 1986 the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC) adopted an additional objective, to enhance the interaction between researchers in the health sciences and industry by implementing joint university-industry programs. The MRC also placed renewed emphasis on women's health issues and on the inclusion of greater numbers of females in clinical trials, since women traditionally were excluded from clinical trials due to concern over possible effects on monthly hormone cycles and pregnancy.

When the umbrella under which Canadian research is conducted became the CIHR in 2000, the health research mandate was altered to reflect current needs. The research agenda included health services research along with other under-developed areas like population health. In addition, more research has been funded on targeted areas of priority such as diabetes, obesity, aging and infectious diseases. The mandate also expanded to include knowledge translation, whereby the research results can be transformed into policies, practices, services and procedures.

The institutes that comprise the CIHR help determine which medical research studies are conducted in Canada. The institutes fund the Canadian research projects deemed to provide the most benefit to the health of Canadians; the funded topics are myriad.

Issues in Medical Research

Medical research critics claim that advances in medical research have led to little improvement in health status. Some blame this on inadequate communication among workers in the health sector and recommend an increase in the number of clinicians conducting research to improve the introduction of new knowledge into health care and to increase treatment-oriented research. Others charge that the conservative nature of the peer review system precludes progress of innovative science, and they advocate the participation of a greater variety of health professionals in medical research, eg, nurses and pharmacists, who have received less support in Canada than basic and clinical researchers. Canadian researchers and research institutions have worked to improve communication procedures between health-care professionals, and to be more inclusive of the various health professionals in medical research. This has led to a highly diverse group of people working in the field, and is more reflective of the changes in modern Canadian society.

There is also ongoing debate about the appropriate balance between curiosity-driven and targeted research, and between research that is oriented towards costly, technologically sophisticated medical treatments and more broadly based epidemiological and environmental medicine.

Ethics remains a vital issue in health research (seeMEDICAL ETHICS; BIOETHICS). The establishment of the CIHR altered the ethical framework for health research in Canada. The MRC helped establish guidelines for the safe and ethical conduct of human experimentation, research with animals and the use of hazardous and infectious agents. However, the guidelines were not law and there was a need to formally address ethics.

The CIHR is mandated by Parliament to adhere to the highest international ethical standards, to apply ethical principles to health research, and to monitor and evaluate ethical issues. Ethics is a shared responsibility among various groups that extend across all levels of the CIHR. The standing committee on ethics identifies emerging ethical issues, while the ethics office develops and implements ethics in research policies. Each institute advisory board has an ethics designate, and the peer review committees that help to determine project funding include a focus on ethics. There is additional support for ethical issues related to research integrity and stem cell research. In addition, the 3 federal research agencies, CIHR, the National Science and Engineering Research Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, jointly created the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics to promote ethical research involving humans in 2001.

International aspects of research are becoming more critical with the increase both in health problems (such as AIDS and pandemic influenza) that face many nations and in multinational studies to examine such problems. New developments, such as cloning and gene identification, present a host of ethical issues. The implications for the misuse of some technologies create what some might view as obstacles to research. The potential uses of cloning have caused the governments of many countries, including Canada, to work toward legislation that will restrict its application. Genetic research, in particular, presents several ethical dilemmas. The ability to identify genomes raises the issues of privacy, confidentiality and autonomy and raises some serious questions for future medical research. Does anyone have the right to genetic information about another individual? Will there be a distinction made between genetic technology for therapeutic purposes and using it to enhance an individual's characteristics? Will such technology change the way we view ourselves and how we define normal/abnormal?

See alsoHUMAN GENOME PROJECT.

Future of Medical Research

The health-care system in Canada is changing. Developments such as the increased recognition of the contribution of environmental and behavioural factors to mental and physical health, the growing focus on cost containment and the allocation of scarce resources, the significant rise in the number of women in medicine and research, the increased need for chronic-disease care in an aging population, the trend towards home care and away from hospital care, and the increase in hospital-based research institutes have all influenced the nature and extent of medical research.

Many of the discoveries of medical research, such as those that have recently offered new abilities to manipulate genes, to perform in vitro fertilization and embryo experimentation, to transplant organs and to screen for genetic problems, will continue to require excellent research by scientists. However, the growing social and ethical issues raised by such research will necessitate closer co-operation between scientists and the Canadian public. Scientists can help the public understand the implications of new knowledge, and the public needs to exercise its responsibility in guiding the extent, conduct and application of medical research in Canada.

The increase in privatized health-care services across the country will likely influence future medical research. Provincial and federal governments will be challenged in the future to balance the research needs of Canadians against the research wants of corporate profit-based medical care.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom