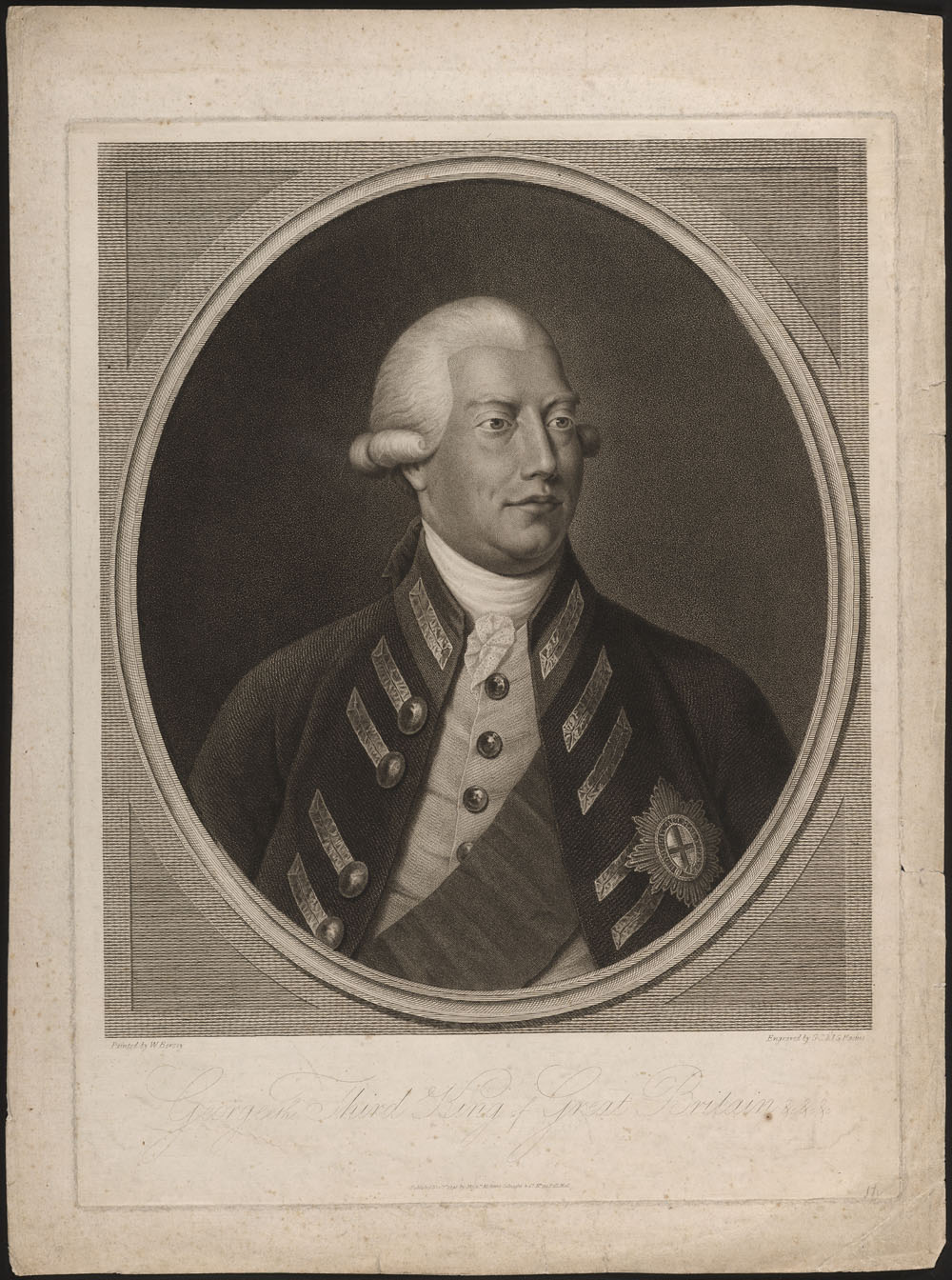

King George III (born Prince George William Frederick on 4 June 1738 in London, United Kingdom; died 29 January 1820 in Windsor, United Kingdom), King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1760 to 1820 and elector and then King of Hanover. George III was the first monarch to reign over English and French Canada. He granted royal assent to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Quebec Act of 1774 and Constitutional Act of 1791. Following the American Revolution, thousands of United Empire Loyalists, who were loyal to King George III, received Crown lands in Upper and Lower Canada and the Maritime provinces.

Early Life

The future King George III was the son of Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales and Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. He was raised with his eight siblings at Leicester House in London, receiving a comprehensive education from private tutors in languages, science, art and music. In 1751, Frederick died and the 12-year-old Prince George was made Prince of Wales by his grandfather King George II.

Accession to the Throne

On 25 October 1760, King George II died and his 22-year-old grandson succeeded him as King George III. Upon his accession, George III granted income from the Crown lands to the British Treasury in exchange for a Civil List payment in support of the royal family. This financial arrangement continues to shape the modern monarchy, which is funded by the sovereign grant in the United Kingdom. The new king faced immediate pressure to marry a suitable princess and become the father of an heir to the throne.

Marriage and Children

On 8 September 1761, King George III married Princess Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in the Chapel Royal at St. James’s Palace in London; they met on their wedding day. On 22 September, their coronation took place at Westminster Abbey in London. King George III and Queen Charlotte had 15 children: George, Prince of Wales (1762–1830), who reigned as King George IV from 1820 to 1830; Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827); Prince William, Duke of Clarence, who reigned as King William IV from 1830 to 1837 (1765–1837); Charlotte, Princess Royal (1766–1828); Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820); Princess Augusta (1768–1840); Princess Elizabeth (1770–1840); Prince Ernest, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale (1771–1851), who reigned as King of Hanover from 1837 to 1851; Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex (1773–1843); Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (1774–1850); Princess Mary (1776–1875); Princess Sophia (1777–1848); Prince Octavius (1779–83); Prince Alfred (1780–82); and Princess Amelia (1783–1810).

Two of George III’s sons were the first members of the royal family to visit British North America. As Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV, visited Newfoundland in 1786 and Nova Scotia in 1787 as captain of HMS Pegasus. Prince Edward resided in Quebec City from 1791 to 1793 and Halifax from 1794 to 1800, becoming Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in North America in 1799. Prince Edward was the namesake of Prince Edward Island and the father of Queen Victoria.

Reign

George III was the first British monarch from the House of Hanover to be born in Great Britain. His public image early in his reign was that of an English country squire, nicknamed “Farmer George” in political pamphlets. He was concerned with his public image and reportedly introduced the Court Circular, which is still the official report of royal engagements in the press, because he was upset by inaccurate coverage of the royal family in the newspapers. George III made generous donations to charity, setting precedents for the involvement of royalty in philanthropy that continues to the present day. He had a wide range of artistic and scientific interests and founded the Royal Academy of Arts. His book collection forms the foundation of the modern British Library. As a constitutional monarch, George III usually acted on the advice of his ministers in Great Britain but exerted some personal influence regarding policy in the British Empire and Ireland.

Royal Proclamation of 1763

George III became King during the Seven Years’ War, which concluded with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, confirming the British conquest of New France. The victory had been achieved with the support of Indigenous allies in North America. In January 1763, Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont, Secretary of State for the Southern Department (now the Home Office), wrote to Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in North America during the Seven Years’ War:

His Majesty having it much at heart to conciliate the Affection of the Indian nations, by every Act of strict Justice, and by Affording them His Royal Protection from any Incroachment on the lands they have reserved to themselves.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 reserved the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains as Indigenous territory and decreed that all land transfers be negotiated through agents of the Crown. In Canada, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 became known as the “Indian Magna Carta” and continues to be upheld by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In contrast, the proclamation was opposed by American colonists interested in westward expansion. Representatives of 24 First Nations gathered at Fort Niagara the following year and ratified the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in the 1764 Treaty of Niagara.

Royal Marriages Act of 1772

In 1771, George III proposed the Royal Marriages Act to parliament in response to his younger brother Prince Henry marrying a non-royal spouse. The Royal Marriages Act, which received royal assent in 1772, decreed that all descendants of King George II (except for the descendants of princesses married to foreign princes) required the monarch’s permission to marry. The Royal Marriages Act remained in force until 2015, when the Succession to the Crown Act 2013 came into force in the United Kingdom, Canada and other Commonwealth realms. Today, only the first six people in the line of succession need the monarch’s permission to marry.

Quebec Act of 1774

While the Royal Proclamation of 1763 attempted to assimilate French Canadians into English legal and social structures, the Quebec Act of 1774 — which came into effect in 1775 — recognized the Roman Catholic Church, the French system of civil law and the property rights of French Canadians. The Quebec Act responded to recommendations sent to the king by governors of Quebec James Murray and Guy Carleton. George III supported the Quebec Act personally over the objections of the mayor of London, who petitioned the king to refuse royal assent to the legislation. English barrister and historian John Adolphus wrote in 1840, “In terminating the [parliamentary] session [in 1774], the King applauded the Quebec Act, as founded on the clearest principles of humanity and justice, and calculated to produce the best effects in quieting the minds and promoting the happiness of Canadians.”

American Revolution

King George III is most famous today as the British monarch during the American Revolution, from 1775 to 1783, which included a failed invasion of Quebec in 1775. It was the British parliament, not the king, that drafted the “Intolerable Acts” of 1774, which were intended to reassert British authority following the Boston Tea Party. Yet George III became personally associated with British oppression of the American colonists after he issued a 1775 Proclamation of Rebellion, declaring the revolutionary war to be “a rebellion” and denouncing the rebels for “traitorously preparing, ordering and levying War against Us.”

The King was confident of a British victory, writing to Lord Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies, “I cannot help being of [the] opinion that, with firmness and perseverance, America will be brought to submission.” The American Declaration of Independence declared George III “a Tyrant […] unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

George III’s correspondence shows that he took a strong interest in military strategy throughout the American Revolution, including the number of soldiers and blankets required and the nature of the military and naval support provided to the American colonists by France. George III was also personally concerned with the resettlement of United Empire Loyalists following the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

United Empire Loyalists

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, thousands of former residents of the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to King George III fled to British North America. Sir Guy Carleton gave settlers the honourary title of United Empire Loyalist, and they received grants of Crown lands in King George’s name.

Their arrival prompted the political reorganization of British North America. The Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the Province of Quebec into Upper Canada (part of modern-day Ontario) and Lower Canada (part of modern-day Quebec). Approximately 30,000 Loyalists settled in the Maritime provinces, 2,000 settled in Lower Canada and 7,500 settled in Upper Canada.

Historian Jane Errington noted the king’s role in differentiating British North America from the newly independent United States, writing in her 1987 book, The Lion, the Eagle and Upper Canada: A Developing Colonial Ideology, “George III gave the colonists, and particularly their leaders, a unique identity — one distinct from that of their wayward cousins in the south.”

Acts of Union

King George III and the British government also faced unrest closer to home. The American Revolution and French Revolution inspired political upheaval in Ireland. At the time, Ireland had its own parliament, but the Catholic majority had little political power. From May to October 1798, a group of revolutionaries known as the United Irishmen fought for full independence from Great Britain but were defeated.

Fears of further unrest and invasion from France led to the 1800 Acts of Union. The legislation was passed by the parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland and created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a single parliament based in London. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger intended the Acts of Union to be followed by wider social and political reforms, including Catholic Emancipation. George III, however, opposed Pitt’s proposed reforms because, in contrast to his support of the Quebec Act, he considered official recognition of the Catholic Church in the United Kingdom to be contrary to his coronation oath as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Pitt the Younger resigned in protest, and popular discontent continued in Ireland into the 20th century.

Declining Health

George III suffered from extended periods of mental illness in 1788–89, 1801, 1804 and 1810 to 1820. Since the 1960s, the prevailing theory concerning George III’s declining mental health was that he suffered from acute porphyria, but recent analysis of his handwriting suggests that he may have suffered from bipolar disorder — a diagnosis favoured by his most recent biographer, Andrew Roberts.

Golden Jubilee

George III was the first monarch to have a Golden Jubilee that was celebrated in the United Kingdom and wider British Empire. In contrast to the subsequent Golden Jubilees of Queen Victoria (1887) and Queen Elizabeth II (2002), the celebration of George III’s Golden Jubilee took place in 1809, on the 49th anniversary of his accession — that is, when he entered the 50th year of his reign. Celebrations took place throughout the British Empire. In 1810, the Upper Canada Assembly passed a formal declaration congratulating George III on his Golden Jubilee.

Regency

Following the death of his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia, in 1810, George III’s mental health deteriorated rapidly. In 1811, the Care of King During His Illness, Etc., Act allowed the future King George IV to act as regent, reigning on behalf of his father. The last decade of George III’s reign is, therefore, known as the Regency period. George III spent his last years in seclusion at Windsor Castle and died there of pneumonia in 1820.

Legacy in Canada

George III reigned for 59 years, the third-longest reign in British history, after the 63-year reign of his granddaughter Queen Victoria and the 70-year reign of Queen Elizabeth II. There are many places in Canada named for King George III, including Kingston, Ontario; the province of New Brunswick; the Strait of Georgia in British Columbia; Georgetown, Newfoundland and Labrador; and Georgetown, Prince Edward Island.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom