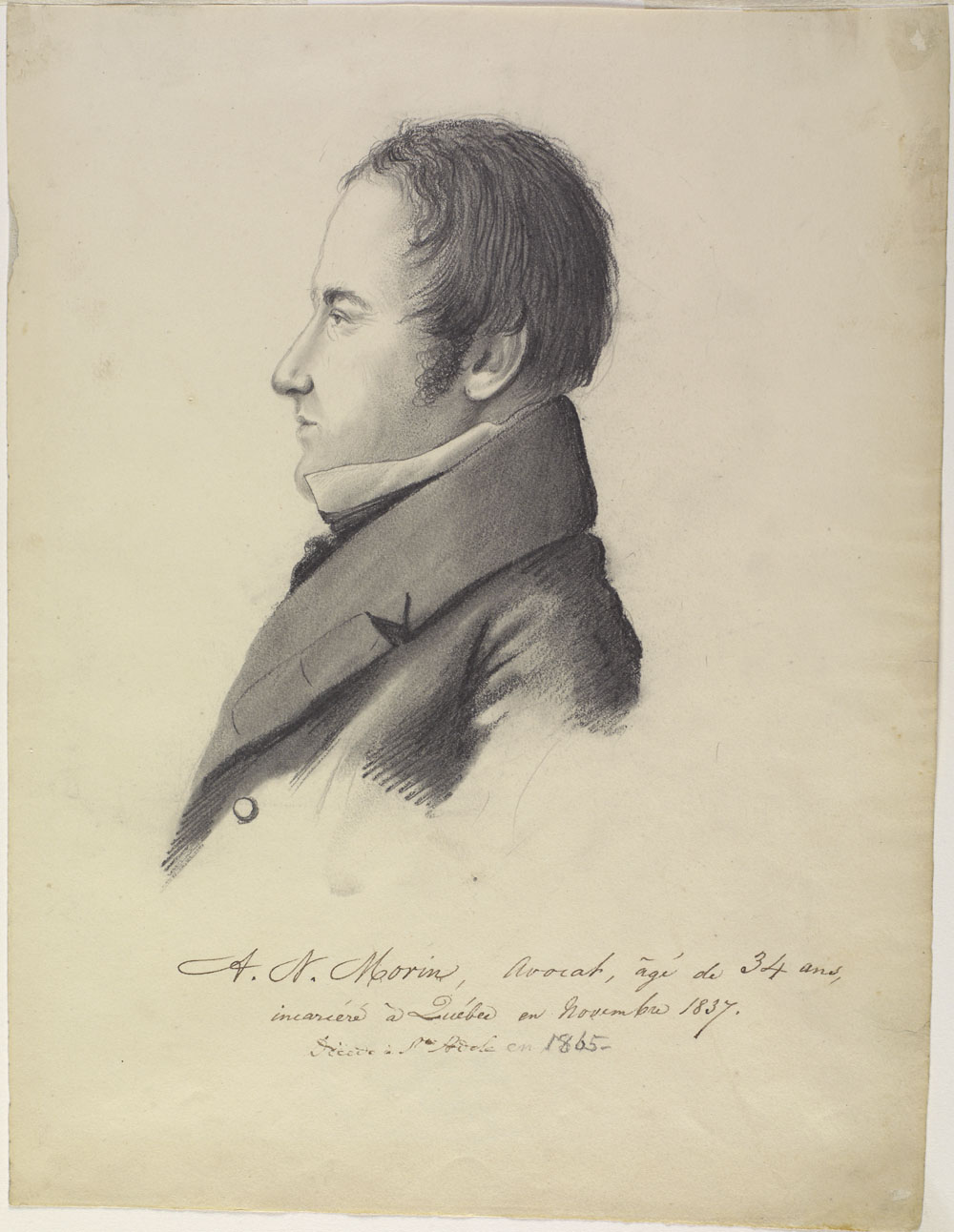

Founding

First circulated on 9 November 1826, La Minerve was created by Augustin-Norbert Morin, one of French Canada’s most important nationalists. Following the closure of Le Canadien, the party’s official mouthpiece, there were no French-language newspapers that endorsed the party’s ideology. The only newspaper that did so was the English-language Canadian Spectator, published by Jocelyn Waller. La Minerve was founded to fill this role. Under Morin, the newspaper struggled to gain subscribers, which led to financial difficulties. In fact, a mere 20 days after publishing its first issue, Morin stopped. A few months later, he sold it to fellow Patriote Ludger Duvernay.

Ludger Duvernay, Pre-rebellion Years (1827‒37)

It was under the guidance of Ludger Duvernay that La Minerve is best remembered. Though the newspaper had a modest number of subscribers (1,300 by 1832), its influence was significant as its editorials were frequently read out loud at public gatherings for the illiterate of the colony. It became the party’s most influential mouthpiece and according to Morin, the colony’s “national newspaper.” Many Patriote leaders, including Morin, Louis-Joseph Papineau and Denis-Benjamin Viger, penned editorials for the newspaper.

La Minerve endorsed the more radical side of the party, frequently critiquing the moderate views of Étienne Parent’s Le Canadien, John Neilson’s The Quebec Gazette and Clément-Charles Sabrevois de Bleury’s Le Populaire. La Minerve even supported an armed insurrection, and in the weeks leading to the Canadian Rebellion, it published numerous editorials inciting the population to revolt. For instance, on 30 October 1837, the newspaper proclaimed: “It is in these times of extraordinary crisis that you unite to uphold your rights and denounce the tyranny of a government that remains odious to every Canadian Patriote. Today, you are providing a noble example for all! Your compatriots admire you!… We are ready to sacrifice what is most important to us to free the soil on which we were born…from vile bondage.”

Ludger Duvernay, Post-rebellion Years (1842‒52)

Following the Rebellion, the newspaper shut down for five years after Duvernay escaped to the United States and remained in exile. In 1842, at the demand of his former Patriote colleague Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, Duvernay returned to Lower Canada and re-established La Minerve. However, this new Minerve was not the radical newspaper of old, but a more moderate version. La Fontaine wanted Duvernay to use it to endorse his conciliatory position. Though the newspaper continued to critique some of the policies of the Act of Union, it applauded La Fontaine’s struggle for responsible government. The newspaper even opposed Louis-Joseph Papineau’s return to Canadian politics in 1848, openly critiquing his radicalism and referring to him as a “great agitator.”

Nevertheless, the newspaper was not always comfortable with its new identity. For instance, though the Reformers opposed the annexationist movement — a movement led by the colony's English-speaking economic elite and the Rouges who maintained that Canada should join the United States — La Minerve was much more nuanced (see Annexation Association; Manifest Destiny). It agreed with the annexationists that in the wake of the corn laws (see Canada Corn Act), annexation could spare the colony from economic difficulties. On 12 July 1849, the newspaper even stated: “We have always considered our colonial existence as transitory and have always worked to prepare ourselves for any eventuality or change that time and circumstance may bring about… Annexation has never frightened us.”

Post-Duvernay Years (1852‒99)

Following Duvernay’s death in 1852, the newspaper transformed from moderate and reformist to conservative. Ownership first passed on to his sons, Louis-Napoléon and Ludger-Denis. During their tenure, they employed editors with close ties to the Conservatives, including Évariste Gélinas (1861‒65) and Joseph-Alfred Norbert Provencher (1865‒69). Provencher even ran for the Liberal-Conservative Party in 1867, and used the newspaper to defend Confederation.

In 1869, Arthur Dansereau became the new editor-in-chief, and in 1879, the sole owner after the brothers sold off their shares as a result of financial difficulties. Under Dansereau, the newspaper continued to endorse George-Étienne Cartier and the Liberal-Conservative Party.

In 1880, Dansereau sold his shares to the Compagnie d'imprimerie de La Minerve, a group organized by Joseph Tassé, who became the newspaper’s new editor. Under Tassé, the newspaper remained a conservative organ, even defending the party after the execution of Louis Riel, blaming the Métis and Riel of having become “ambitious and grasping.” (see Red River Rebellion). In 1889, the newspaper was leased to Trefflé Berthiaume, who disagreed with Tassé’s editorial policy.The following year, Tassé was dismissed, a decision that led to a legal battle. The case was settled by mutual agreement a year later — Tassé returned as editor and Berthiaume paid no penalties — but the newspaper struggled financially.

In 1892, the struggling newspaper was sold to Eusèbe Sénécal (see also Sénécal). However, it would not survive much longer. According to historian Jacques Michon, financial difficulties, transformations in the newspaper world, and more importantly, Liberal victories in both Québec and Ottawa, resulted in the end of the conservative mouthpiece. It stopped circulating in 1897. Though a conservative interest group attempted to relaunch it a year later, it ended for good in 1899.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom