Lacrosse, the Creator’s Game, is known to various First Nations in North America by many different names, including baggataway (Algonquian), kabocha-toli (Choctaw) and tewaarathon (Mohawk). To Indigenous peoples, the game is spiritual and its rituals are a prominent component in creation stories, specifically for the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois).

The modern name, “lacrosse,” has French origins. The first published reference to the game as “lacrosse” was in reports written in the 1630s by French missionaries living among the Huron-Wendat. Although some believe the game was so named because the stick resembled a bishop’s “crosier,” other scholars point out that by this time the French used the expression jouer à la crosse to refer to any game played with a curved stick and ball. Whatever its origins, the name signalled the beginning of the change from a spiritual game to the modern sport.

European observers were fascinated by the game’s seemingly warlike qualities. Sometimes, thousands of players competed across ball fields that stretched for several kilometres, and played for a number of days. It appeared a rough-and-tumble display of mayhem to Europeans.

However, what many Europeans didn’t realize is that the game performed important spiritual, social and political functions. Warriors would fast, purge and exercise to make their mind, body and spirit acceptable to the Creator, because in the end the game was being played “for the entertainment of the Creator.” It was a medicine game and in many cases it was used to heal members of the community or solve disputes, such as hunting ground rights.

As European contact increased, the newcomers were drawn to the game. Interest was particularly high in 19th-century Montréal. In 1834, a group of businessmen organized exhibition games at the racetrack at Ville Saint-Pierre between seven-player teams from Kahnawake and Akwesasne. These were the first “urban,” contained games — traditionally, the game was played by large groups in the fields and woods on ancient ball fields. European influence was beginning to turn the medicine game into a sport.

Montréal sportsmen also picked up balls and sticks to try their skills, learning from their Mohawk neighbours. One citizen in particular was fascinated with the game. As a teenager, William George Beers had spent a great deal of time with the Kahnawake Mohawk, who were situated across the St. Lawrence River, just south of Montréal. In August 1860, Beers participated in a “Grand Display of Indian Games,” an exhibition put on for the visiting Prince of Wales. The demonstration included a match between two Indigenous teams followed by another match between an Indigenous team and one made up of local Anglo-Canadian players (Beers played goaltender for the Montréal team). A month later, Beers published a pamphlet laying out basic rules, number of players and field size — a key development in the modernization of the sport.

Beers was an inquisitive and passionate man who became one of Canada’s leading dentists. He was also an ardent nationalist. During the American Civil War, Beers formed a company of the Victoria Rifles Volunteers, in anticipation of conflict between the United States and Britain after the Trent Affair of 1861. The company drew mainly from the Beaver and Montreal Lacrosse Clubs.

Around the time of Confederation, Beers felt that the new Dominion of Canada needed its own game, a game that sprang from the Canadian soil and its people rather than a British sport like cricket.

What better game than lacrosse — traditionally, the sticks were hickory (a sacred wood) and strung with deerskin or groundhog leather, the balls carved from wood or made of deerskin. The equipment for playing this game came directly from the flora and fauna of Canada. The game seemed to rise from the very land, itself.

Beers and his contemporaries were also inspired by images of the “noble savage” — a romanticized stereotype about Indigenous peoples as uncorrupted by modernity. They hoped that in adopting and codifying this ancient Indigenous game — one that required physical strength and manliness — they could create a vigorous nation of Canadian men well-suited for life in the North.

Beers campaigned for lacrosse to be Canada’s official national sport, and played a major role in the formation of the National Lacrosse Association in September 1867, only two months after Confederation. Many therefore consider 1867 the beginning of the modern game of lacrosse.

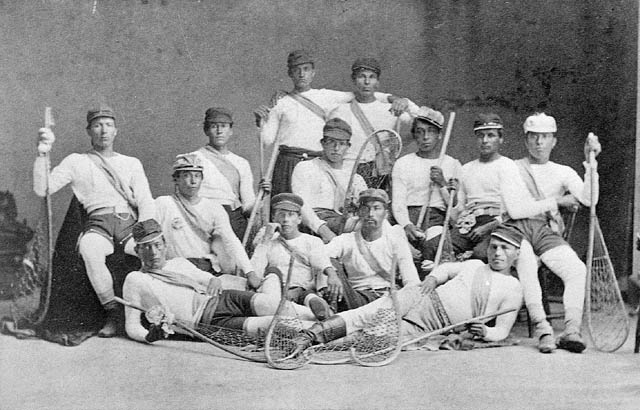

That year, a contingent of players travelled to England to showcase the game. This group was made up of amateur players from the Montreal Lacrosse Club and 16 paid Kahnawake players. The tour, organized by Captain W.B. Johnson, was poorly planned and wasn’t particularly successful.

Beers played a greater role in two subsequent junkets made in 1876 and 1883, both of which attracted great interest overseas. The intent of the tours was to promote lacrosse and — particularly in the case of the 1883 tour — immigration to Canada. Like the 1867 trip, these tours included a team of paid Indigenous players, who were the prime attraction for a curious British public. During the 1876 tour, the Kahnawake team sported red-and-white striped uniforms, wearing blue caps decorated with ornamental bead work and two to three red feathers. In contrast, the Montréal team wore uniforms of plain white, grey and dark brown. News reports focused on the different appearance and playing style of the two teams — the “scientific” teamwork of the Montréal team versus the individual style of the Kahnawake players. Between games, the Indigenous players staged snowshoe races, as well as mock war dances and powwows. This stereotypical portrayal of Indigenous culture was deliberate. From a purely commercial standpoint, these representations were popular among the British public and helped bring in the crowds. The Montréal team won three-quarters of the matches, suggesting that they may have been staged, a “symbolic representation of Britain’s New World conquests,” according to historian Donald Fisher.

The 1883 tour was similar, with a Kahnawake team competing against a white team comprising members of Montréal and Toronto lacrosse clubs. The teams barnstormed the United Kingdom, playing 62 games in 41 cities through Scotland, Ireland, Wales and England in just over two months. As in the earlier tours, the players not only demonstrated the game but also shared First Nations culture of song, dance and drumming. During these events, hundreds of thousands of brochures promoting immigration were distributed to the local communities.

Lacrosse also spread to the United States in the late 19th century. Canadian immigrants formed clubs in places like New York City and Boston, while Indigenous players toured a number of American cities. Lacrosse became a popular pastime among the elite of the American Northeast, played at universities and private clubs.

By the 20th century, lacrosse looked very different than the Creator’s Game of the pre-colonial period. “But this act of cultural appropriation did not amount to a zero-sum equation,” writes Fisher. “Although white clubs eventually dominated the playing of the game and white rule makers transformed the way it was played, [Indigenous players] did not vanish from the game… Instead, [Haudenosaunee] athletes learned the new modern version of the game, although they never forgot how their forefathers had played the game.”

In 2017, as we commemorate the 150th anniversary of modern lacrosse, the sport is played around the world. International men’s lacrosse is dominated by three powerhouse teams: the United States, Canada and the Iroquois Nationals — the only Indigenous team sanctioned to compete in international competition. One of the top teams in the world, the Nationals honour the history and meaning of the Creator’s Game:

Before each game, players are reminded of the reason for their participation. Lacrosse is played for the enjoyment of OUR CREATOR. Lacrosse should not be played for money, fame, or personal gain; you should be humble and of a good mind when you take your lacrosse stick in hand.

Some players will ask the spirit of an animal for guidance so that he may have the eyes of the Hawk, and the agility of the Deer. There is often a blessing where sacred tobacco is placed into the fire so that the smoke will rise, carrying this message to the land of the creator…

Today, when the Haudenosaunee see their young men play, it makes all who are in attendance feel proud to be the originators of such a great game.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom