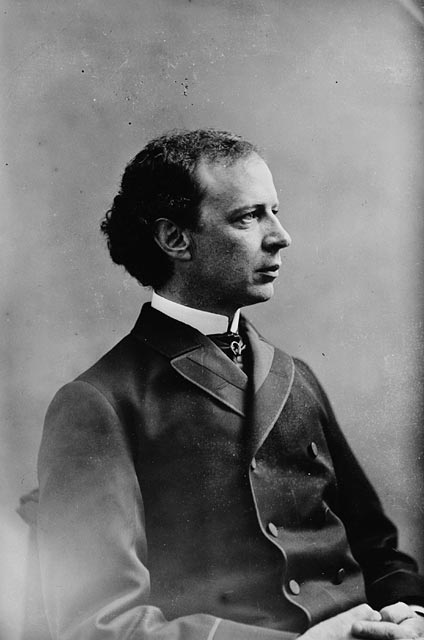

Wilfrid Laurier first accepted leadership of the Liberal Party in a letter addressed to Edward Blake, who had chosen Laurier to replace him as leader. Preferring the privacy of his library to the battlefield of politics, he was uncertain. He admitted as much in his letter to Blake, dated 18 June 1887: “I know I have not the aptitude for it,” Laurier admitted, “and I have a sad apprehension that it must end in disaster.” Five days later, the news became public.

He had come a long way by that point. A radical in his youth, Laurier had close ties with hardline members of the Parti rouge, and opposed Confederation, a project he described as “the tomb of the French race and the ruin of Lower Canada” in Le Défricheur, a party newspaper he edited. When Confederation became a reality, however, the young lawyer decided to join the cause. Seeing that radical liberalism aroused mistrust, Laurier became a moderate.

Parallel Streams

The 1885 hanging of Louis Riel, and the debate that followed in the House of Commons, completed Laurier’s transformation. In taking up the Métis cause, he defined his conception of a Canadian nation built on two founding cultures, English and French. In the following year, he compared the two cultures to two parallel currents of water, those flowing from the Ottawa River and the St. Lawrence. The currents meet below the island of Montréal, he said, where they remain separate and distinct before spilling into the Atlantic, “bearing the commerce of a nation upon its bosom — a perfect image of our nation.” He defended this definition of Canada all his life. For him, it was the only guarantee of national unity.

The Sunny Way

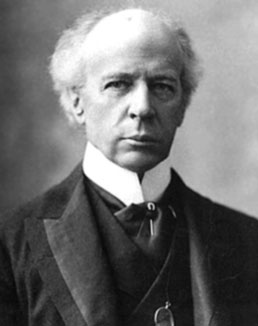

After some difficult years in opposition, Laurier finally triumphed. On 23 June 1896, at age 54, he became the first French Canadian prime minister. Laurier would lead the country for 15 years, the longest uninterrupted term for a Canadian prime minister, with a policy of systematic compromise. As historian Réal Bélanger writes in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Laurier was at once a charmer and a manipulator, a politician who “cultivated the art of ambiguity… a strategy for achieving his purposes more readily in a dog-eat-dog environment.”

In truth, Laurier's famous ability to compromise sometimes left everyone dissatisfied. His solution to the thorny issue of Catholic schools in Manitoba pleased the Protestant majority at the cost of the Catholic minority (see Manitoba Schools Question). On the campaign trail in 1896, Laurier proposed his now-famous “sunny way,” calling for fairness and generosity towards the Catholic minority and arguing that solutions should be found through negotiation, not by imposition. His later retreat on Catholic education rights in the formation of the new provinces in the North-West (Alberta and Saskatchewan) did not enhance his place in history. In the long term, it ended any hope of Canada becoming an authentically bilingual country.

Canada’s Century

Laurier had more success on economic questions. In 1897, he managed to satisfy the contradictory interests of the country's protectionists and proponents of free trade (see Reciprocity). With the support of Clifford Sifton, minister of the interior, he carried out a vigorous immigration policy (see The Great Western Migration). The West became the most dynamic factor in the economic growth of the country. A sunny optimism prevailed for “Canada's century.”

“Canada has been modest in its history, although its history,” said Laurier in 1904, “is only commencing.… The 19th century was the century of the United States. I think we can claim that Canada will fill the 20th century.”

In external relations, his objective was to improve Canada's position relative to both the United States and Great Britain. In 1897, he opposed efforts by British authorities to draw Canada into a closer imperial federation. During the South African War (1899–1902), he again chose compromise between English Canadians — who supported military involvement — and French Canadians — who vehemently opposed it. By allowing for the recruitment of a contingent of volunteers, partially paid for by Britain, Laurier found the middle ground. When imperialists demanded that Canada assist the British Royal Navy, which was struggling to stay ahead of the German navy, Laurier compromised. In 1910, he helped pass the Naval Service Act, which established the Naval Service of Canada (later, Royal Canadian Navy).

In 1911, Laurier put his foot wrong and campaigned on a policy of free trade with the United States — a platform that had failed him 20 years earlier, in the election of 1891. The opposition talked about the destruction of the country and made vicious attacks on the old leader. He was defeated.

20th-Century Liberalism

Laurier devoted the last stage of his political career to rebuilding his party. He hounded the new prime minister, Robert Borden, from across the aisle in Parliament. He saw the country torn asunder over Borden's coercion in forcing conscription, and he lost another election in 1917. The cruel defeat did not leave Laurier personally beaten. Despite his years, he announced that a Liberal congress would take place to restructure the party. Unfortunately, he died on 17 February 1919, aged 77, before the congress could take place.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier was one of the central figures of Canadian history. By his tolerance and compromise, he had carried out the plan of Confederation and brought Canada to the status of nationhood. After the conscription crisis, he began to rebuild the shattered Liberals. By bringing them together as a bicultural institution that represented the country as a whole, he devised the form of Liberal Party politics that ruled Canada for most of the 20th century.

Laurier summed up his own philosophy best: “I am branded in Québec as a traitor to the French, and in Ontario as a traitor to the English. In Québec I am branded as a jingo, and in Ontario as a separatist.… I am neither. I am a Canadian. Canada has been the inspiration of my life. I have had before me as a pillar of fire by night and a pillar of cloud by day a policy of true Canadianism, of moderation, of conciliation.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom