King Louis XV, king of France from 1715 to 1774 (born 15 February 1710 in Versailles, France; died 10 May 1774 in Versailles, France). Louis XV was the last French king to reign over New France, ceding French Canada to Great Britain with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Early Life

Louis was born in the reign of his great-grandfather King Louis XIV. The infant prince was the younger son of the King’s grandson Louis, Duc de Bourgogne (Burgundy), and Marie Adelaide of Savoy. The couple had three sons, but the first lived only briefly (1704–05). In 1712, the Duc and Duchesse de Bourgogne and both their young sons contracted measles. The two-year-old Louis’s governess, Charlotte de la Motte Houdancourt, Duchesse de Ventadour, nursed him herself and prevented doctors from subjecting him to bloodletting — the treatment applied to the rest of his family. Louis’s parents and elder brother died of measles. As Louis’s paternal grandfather had died of smallpox the previous year, Louis became the Dauphin of France, his great-grandfather’s heir.

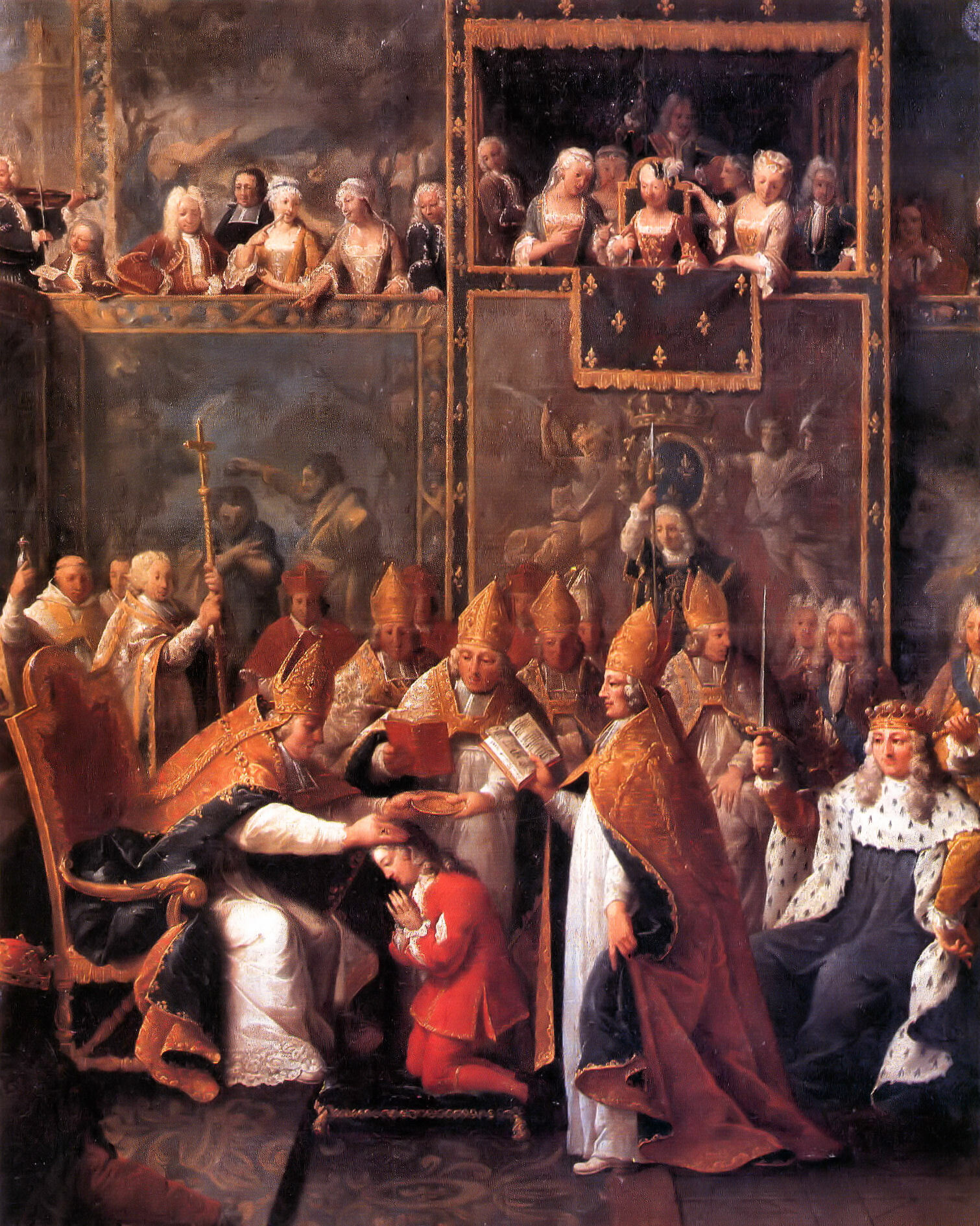

Accession to the French Throne

On 1 September 1715, Louis succeeded his great-grandfather King Louis XIV as King of France and became King Louis XV. After his accession, the five-year-old opened his first lit de justice — a formal session of the Paris judicial parlement that registered royal edicts — accompanied by his governess. As a child, Louis XV received foreign visitors, including Peter the Great of Russia in 1717. His great-uncle Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, served as regent of France from 1715 to 1723, when the young king turned 13 and legally came of age. On 25 October 1722, Louis was crowned king at Reims Cathedral. His cousin Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, became chief minister in 1723 but was soon dismissed by the young king. From 1726 to 1743, France was effectively governed by André-Hercule de Fleury, who had been Louis XV’s tutor and had great influence over the king.

Marriage

At the age of 11, Louis XV was engaged to his three-year-old cousin, Mariana Victoria, the daughter of King Philip V of Spain and Elizabeth Farnese. Mariana Victoria lived at Louvre Palace in Paris from the age of three to seven, when Louis sent her back to Spain so that he could marry a bride who was old enough to consummate the marriage and bear children. The rejection of Mariana Victoria caused a temporary diplomatic rift between France and Spain.

On 15 August 1725, 15-year-old Louis was married by proxy to 22-year-old Marie Leszczynska, the daughter of Stanislaw I Leszczynski, the dethroned king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and Catherine Opalinska. Louis and Marie met in person on 4 September 1725, the evening before their wedding at the Château de Fontainebleau, outside Paris. The marriage was initially a close one, but Louis began pursuing other women in 1733 and lived separately from Marie after the difficult birth of their youngest child, Louise Marie, in 1737.

Children

Louis XV and Marie Leszczynska were the parents of eight children: twin girls Louise Élisabeth, Duchess of Parma (1727–59), and Anne Henriette (1727–52), Marie-Louise (1728–33), Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–65), Philippe Louis, Duke d’Anjou (1730–33), Marie Adélaïde (1732–1800), Victoire Louise (1733–99), Sophie Philippine (1734–82), Marie Thérèse (1736–44) and Louise Marie (1737–87). The four youngest daughters were educated at the Royal Abbey of Fontevraud in the Loire Valley to reduce the expenses of the royal household at Versailles. Louise Élisabeth and the Dauphin Louis were the only children of Louis XV and Marie Leszczynska who married and had children of their own. Louise Marie became a nun, and her other sisters remained at the court of Versailles. Marie Adélaïde and Victoire Louise fled the French Revolution in 1791 and settled in Italy. Louis XV also fathered at least a dozen illegitimate children with other women.

Reign

Louis XV reigned for 59 years — the second-longest reign in French history after the 72-year reign of Louis XIV. He was the last monarch to expand France’s territory before the French Revolution, adding the Duchy of Lorraine and the island of Corsica to his kingdom. In his portraits and official statements, he presented himself to the public as an absolute monarch, but rivalries among his ministers and courtiers, conflicts with the Parlements, financial difficulties and the influence of his favourites limited his ability to wield power effectively. Louis reigned during the French Enlightenment, when new ideas concerning rationalism and human progress informed debates concerning politics, religion, science and culture. Louis and his mistress, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Madame de Pompadour, who exerted influence over Louis’s domestic and foreign policy from 1745 to her death in 1764, were artistic and cultural patrons, popularizing the Rococo style of architecture and design among the European elite.

Fortress of Louisbourg

Construction of the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island (Île Royale) began in 1720, when Louis XV was five, and was not completed until 1745, when he was 35. The start of construction was commemorated in France with a medal depicting the young king wearing laurel leaves, which symbolized victory, on one side and the port of Louisbourg on the other side. The bricks for the fortress were largely imported from New England, although some building materials were also shipped from France. As Louis grew older, he was dismayed by the immense cost of building the fortress, which amounted to more than 50 million dollars in modern currency. In 1745, the British seized and sacked the Fortress of Louisbourg during the War of the Austrian Succession, but the fort was returned to the French as part of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748.

The War of the Austrian Succession

Louis XV was involved in a series of dynastic and territorial wars in Europe, which were also fought between the French and British empires in North America. From 1740 to 1748, France and Prussia fought Great Britain, Austria and Russia in the War of the Austrian Succession. The presence of the King and the Dauphin at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745 was popular in France, and Louis was nicknamed “Louis the Well Beloved.” At the end of the war, the French and British governments established a boundary commission to adjudicate territorial disputes in North America. Regional conflicts continued, however, creating the conditions for the Seven Years’ War and the fall of New France.

New France

Louis XIV had made New France a Crown colony in 1663. By the reign of Louis XV, France’s sparsely populated colonies in North America were under increasing pressure from the expanding British population in the Thirteen Colonies (the future United States) and Nova Scotia. In 1750, the departing governor of New France, Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, returned to France and presented Louis XV with his recommendations for the defence of France’s colonies in North America. Some of these proposals were implemented, including strengthening the garrison near the Straits of Mackinac between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan and building outposts at Sault Sainte Marie and Fort Rouillé near present-day Toronto. Louis XV instructed Ange Duquesne de Menneville, Marquis Duquesne, governor general of New France from 1752 to 1755, to “most carefully avoid giving [the British] any just cause of complaint” and to “stand on the most exact defensive” unless attacked by British troops.

The Seven Years’ War

War between French and British colonists and their Indigenous allies resumed in 1754, when future U.S. president George Washington ambushed French Canadian soldiers at the Battle of Jumonville Glen. Washington was defeated by French Canadian officer Louis Coulon de Villiers at the Battle of Fort Necessity in Pennsylvania on 3 July 1754. Formal hostilities between Louis XV and Great Britain’s King George II were declared in 1756. The King concluded an unpopular alliance with France’s traditional enemy, the Habsburg Empire of Austria, against Prussia and Great Britain. Although the conflict is generally known as the Seven Years’ War, it is more commonly referred to as the French and Indian War in North America.

Although French Canadian troops and their Indigenous allies knew the terrain and were experienced in frontier warfare, their efforts were undermined by ineffective leadership from France, inadequate financial assistance and the strength of the British navy. On 26 July 1758, the Fortress of Louisbourg fell to the British after a seven-week siege (the British later destroyed the fortifications in 1760).

Assassination Attempt

Louis XV introduced an income tax, the vingtième (twentieth), to fund the war effort over objections of the Paris parlement. The nobility and clergy were largely exempt from this income tax as they had the option of providing a direct gift to the Crown. The expense and defeats of the Seven Years’ War, the income tax and the suppression of the Paris parlement’s judicial oversight made the King unpopular. On 5 January 1757, Louis was the victim of an assassination attempt. He was stabbed by Robert-François Damiens, who blamed the King for the Catholic Church’s refusal to grant holy sacraments to members of the Jansenist theological movement, which included many members of the Paris parlement. The King survived and Damiens was dismembered by having his arms and legs tied to four horses.

The Fall of Quebec

On 13 September 1759, Quebec City fell to the British at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. In October 1759, King Louis XV asked the French people to bring their silverware and jewellery to the mint in Paris to contribute to the cost of the war, following a precedent set by Louis XIV during the War of the Spanish Succession. Despite these efforts, Montreal and the rest of New France were surrendered to the British by governor general Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial, Marquis de Vaudreuil, on 8 September 1760. For his efforts to resist the British, Louis XV appointed Vaudreuil to the highest level of the Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint Louis— the only French Canadian to receive this honour (see Croix de Saint Louis).

The Treaty of Paris

In 1763, Louis XV agreed to the Treaty of Paris with Britain’s King George III. According to the treaty, France renounced claims to Nova Scotia, Acadia, the island of Cape Breton and all islands and coasts in the St. Lawrence River and Gulf of St. Lawrence. France retained the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon for fishing, and Great Britain returned the sugar-producing Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique to France.

Louis remarked after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, “The peace we have made is neither good nor glorious.” But he was not overly concerned about the loss of New France because revenues from the fur trade and fisheries were exceeded by the costs of defending the colonies. After the loss of New France, Madame de Pompadour reputedly remarked, “Now the King can sleep.” These views were shared by other prominent figures in France. In his 1759 play Candide, Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire wrote, “You know that these two nations are at war for a few acres of snow in Canada and that they spend over this beautiful war much more than Canada is worth.”

Later Life

The Treaty of Paris undermined respect for Louis XV and the French monarchy. France’s standing in Europe declined. Louis did not intervene to prevent the first partition of France’s long-standing ally Poland in 1772. Queen Marie Leszczynska died in 1768, and the King began a relationship with a former milliner, Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry, that lasted until his death from smallpox. Louis XV’s sons predeceased him, and he was succeeded by his grandson, King Louis XVI, who would reign until the French Revolution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom