Canada was deeply unprepared when it went to war at Britain’s side against Germany on 10 September 1939. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was an experienced and shrewd politician who had been in power for nearly 13 years, on and off, since 1921, but few thought he had the grit to lead the country in war. He certainly did not compare favourably, at first glance, to the warlike and aggressive Adolf Hitler in Germany or Benito Mussolini in Italy, or the more stately American president, Franklin Roosevelt or, after May 1940, the pugnacious British prime minister, Winston Churchill. But King surrounded himself with an effective Cabinet of ministers, was guided by a strong and dedicated public service and meddled very little with the professional military men who were raising Canada’s new armed forces. King would guide the country through six painful years of conflict, oversee a massive war effort and make surprisingly few errors in a period of tremendous turmoil, change and anguish.

Hitler and Mobilization

After years of rearming Germany, breaking treaties, threatening neighbours, annexing countries and then invading Poland on 1 September 1939, Adolf Hitler caused the Second World War in Europe. The allies Britain and France, with the backing of the 500-million-strong British Empire — but not the neutral United States — stood up to Hitler and the Nazi party that controlled Germany. The murderous and psychopathic Joseph Stalin ruled the Soviet Union with an iron hand. Stalin, who had starved to death millions of his own people while executing hundreds of thousands more, had a non-aggression pact with Germany, although Hitler would turn on him in June 1941. Italy and Japan, ruled by fascists, naturally sided with Hitler’s Nazis, although there was little co-ordination between the three nations that formed the Axis Powers.

Canada’s Contribution

After declaring war on Germany on 10 September, Prime Minister King and his Cabinet struggled over what role Canada would play in the war. Knowing that French Canada was wary of any overseas military commitment, King and his senior Québec minister, Ernest Lapointe, promised that the war would be a voluntary one for Canadians. This was enough to bring Québec into the war without protests or riots. An equally important issue was that the country lacked a modern military force. Deciding how to position Canada in this war, King was guided by Canada’s actions in the First World War.

From 1914 to 1918, the country had borne any burden in the pursuit of victory and, in the process, had nearly torn itself apart. Canada had produced food, raw materials and munitions in enormous quantities, and it had put more than 620,000 Canadians in uniform. The industrial warfare on the Western Front had led to horrendous losses, with Canada suffering more than 66,000 dead and 172,000 wounded. (See The Canadian Great War Soldier.) The need for more men to fill the ranks had been a constant problem from the midpoint of the war, and it eventually led to the conscription crisis of 1917. Legislated compulsory military service had fractured the country along linguistic, ethnic, class and regional fault lines. King had seen what an unfettered war effort could do to his country, and he vowed not to repeat the same all-out war policy that had led to conscription.

King hoped that the roughly 11.5 million Canadians could be directed towards producing food, supplies and munitions for the Allied forces rather than raising a massive Canadian army, navy, and air force. This would later be classified as a strategy of “limited liability.”

English Canada refused to accept the constrained commitment. Almost immediately, tens of thousands of men enlisted in the three armed forces. King felt the army was forcing his hand toward a more active Canadian role in the war, but there was little that could be done to constrain the creation of a new overseas army. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division went overseas by the end of the year under command of the charismatic Major General Andrew McNaughton. Canada would eventually field the enormous First Canadian Army, consisting of almost half a million soldiers.

Canada also fought in the war at sea. From the first month of conflict, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), which would expand from a dozen warships to more than 400 by the end of the war, began convoy duty in September 1939. Canadian warships guided merchant vessels carrying essential war matériel across the ocean to Britain in the midst of attacks by German U-boats. Keeping open the lifeline to Europe was crucial to the Allied war effort (see Battle of the Atlantic).

King's Government

The war was fought in defence of liberal ideals and freedom. However, King’s Cabinet had invoked the War Measures Act on 3 September. This, along with the Defence of Canada Regulations, allowed for censorship, detainment of citizens without charge, and surveillance. Anyone siding with the enemy in word or action could be jailed. Even the high profile Montréal mayor, Camillien Houde, was not above the law. When Houde spoke out against the war in 1940 and stoked fears that King would bring in conscription, he was imprisoned without trial for four years.

With little happening overseas — Germany had conquered Poland in a lightning-fast war and then turned to face the western Allies in a standoff soon dubbed the phony war — King called an election in March 1940. Canadians clearly believed that King had done his duty in supporting Britain while not alienating Québec. For his careful guidance, he received a massive majority in Parliament. His moderate approach to the war effort was in tune with what most Canadians expected of the country.

Canadians had faith in King and his experienced Cabinet. The very capable J.L. Ralston was moved to the ministry of finance and then to national defence; C.D. Howe was given increasingly prominent roles in running wartime industry; J.L. Ilsley was later finance minister and proved very good at managing the nation’s treasure; and Ernest Lapointe, Charles Power and Louis St. Laurent offered a strong voice for Québec. And the Prime Minister led them all, slowly making and shifting policy to meet each new crisis. King was highly intelligent with well-honed political instincts. His close advisor, Undersecretary of State for External Affairs O.D. Skelton, remarked that, "He plays his hunches." King also felt comfortable delegating authority. While he could be petty, insulting and play ministers off against one another, he had faith in his talented Cabinet. They rarely let him down.

Canada’s Military Leadership

Canada’s navy, army, and air force were all distinct from the British military, with their own units, uniforms, and traditions, even though they fought as part of larger British or Allied formations. The Canadians were also commanded by their own military leaders: General Harry Crerar led the First Canadian Army by the end of the war; Admiral Leonard Murray commanded the air and naval forces fighting the U-boats in the northwest Atlantic; and Air Vice-Marshal Clifford McEwen commanded No. 6 (RCAF) Bomber Group in Europe. Senior Canadian military leaders in the field had the right to play the nationalistic card to avoid a particularly heinous order from non-Canadian superiors. (They reported up through the Allied military structure – but also to Ottawa.) Alas, none ever did, even during disasters like the failed raid on Dieppe, or the RCN's equipment shortfall in 1942, or the relentless and costly bomber attacks against Berlin in late 1943 and early 1944.

King and his Cabinet could have also pushed for greater influence in directing the Allied war policy that was set in London and Washington. After the fall of France in June 1940 and before the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, Canada was Britain’s ranking ally. But King wanted no hand in shaping strategy, feeling it might force him to commit more forces than Canada was able to without resorting to conscription. It was a mistake on King’s part not to demand more influence, since Canada would eventually put an enormous number of men and women in uniform — close to 1.1 million — but have little say over the war’s strategy.

In the most egregious example of how King was left out of the loop by the Allied high command, he was not even told of the date of the D-Day landings (6 June 1944), in which a Canadian division was one of the spearhead formations. No one expected King to be on equal ground with Churchill or Roosevelt, and Stalin sat alone after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, making him a strange and inscrutable ally. But King might have pushed harder and earlier for some influence.

King as War Leader

King, nonetheless, played an important role early in the war by mediating the sometimes difficult relationship between Britain and the neutral United States. A friend to the American president, Franklin Roosevelt, King helped broker some key deals for the increasingly desperate British, like the “destroyers for bases” agreement in August that saw the neutral Americans transfer old destroyers to Britain in exchange for access to British naval bases in the Americas, including in Newfoundland. King also influenced the president to free up funds for the British to continue purchasing American goods.King was able to use his friendship with Roosevelt to ensure that the US and Canada worked closely together on matters of hemispheric defence, and that trade between the two countries was open, fair and relatively equal in volume. With agreements on defence and trade set in 1940 and 1941, Canada could turn its full attention to supplying Britain with crucial war supplies.

Canada also aided Britain and the Allied war effort by administering the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. After tough negotiations between the King government and the British in late 1939 over who would pay for the estimated $1 billion plan, Canada agreed to establish training bases and airfields across the Dominion. Some 131,500 airmen were trained for the fight against the Axis Powers, and many young Canadians were lured to the air force, especially Bomber Command, by the glamour of flying. It would prove to be dangerous and costly but also effective in bringing the war to the German homeland.

After the fall of France to German forces in June 1940, Canada’s war effort changed radically. King’s plan of limited liability was rapidly shed. In the immediate aftermath of the debacle in France, the National Resources Mobilization Actbrought in limited conscription, with no overseas service, to protect Canada. Munitions, food and raw materials, along with a “billion-dollar gift” to Britain to pay for them, transformed Canada into the “arsenal of the Empire.”

All of this was done with skill and energy, although King and his Cabinet were continually tested. When inflation began to rise, the ministers instigated the radical option of putting a cap on wages and prices. King feared that Canadians might revolt, but they accepted it in the name of victory. And the cap succeeded in controlling inflation. Unemployment disappeared by the mid-point of the war, but so did many of the luxury goods that had to be rationed. Most Canadians tightened their belts, bought victory bonds for future days and got on with winning the war from the factory floor or their farms.

Relations with organized labour were always difficult, but King’s Cabinet managed them effectively so that there were no long-term strikes that interfered significantly with wartime production. Nearly two million Canadians were in war-related jobs, including 439,000 women in the service sector and another 373,000 with jobs in manufacturing. A 1944 federal labour code was a concession to labour and it allowed for more unions.

If these were successes, King and his Cabinet also failed at times. Their most egregious act was to order the internment of some 21,000 Japanese Canadians living on the West coast in 1942, in the aftermath of Japan's declaration of war on the Allies. Driven by racism and fear that Japanese Canadians were not to be trusted, this hurtful act was exacerbated by the sale of their property at criminally low prices.

Crisis and Conscription

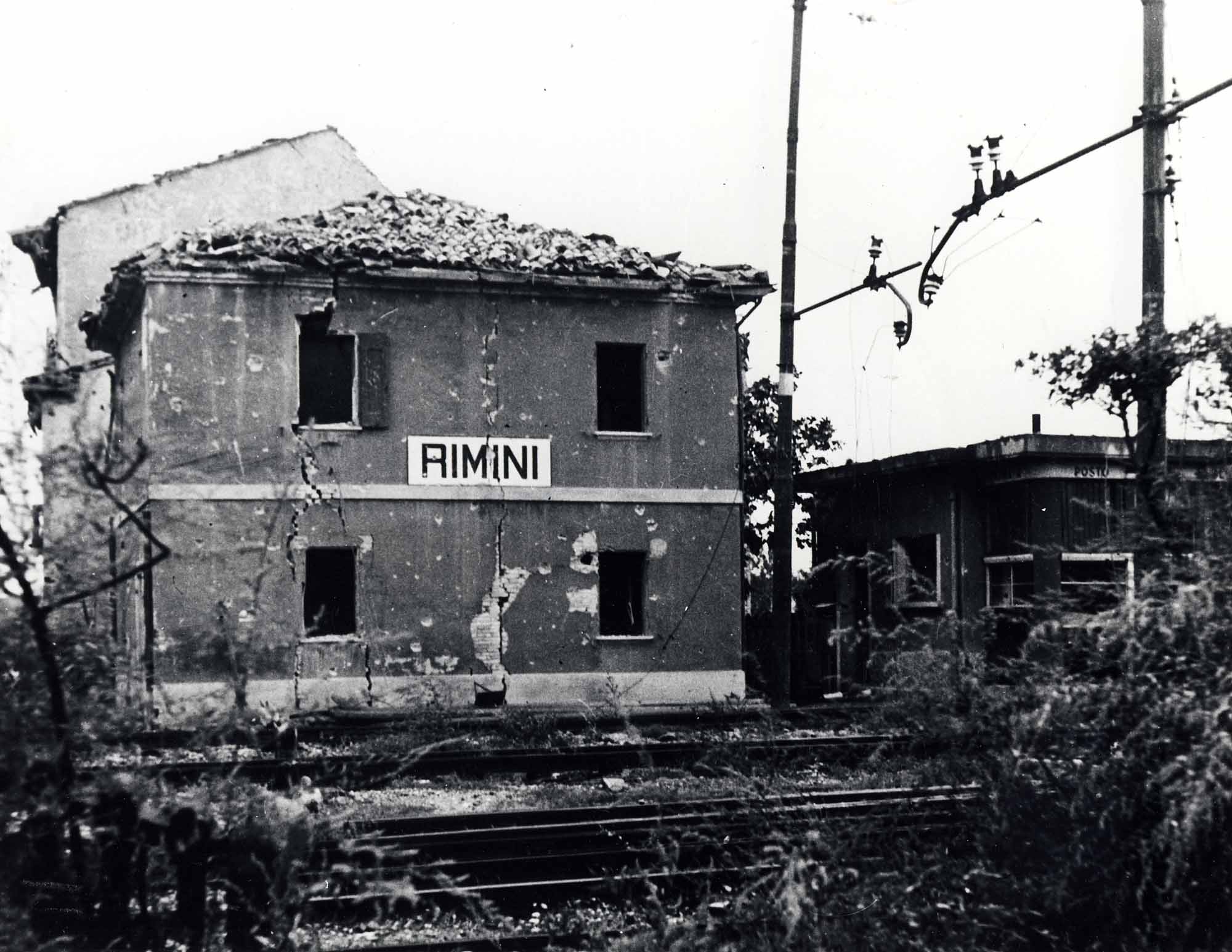

Canadians suffered steady casualties in the Battle of the Atlantic, the air war over Britain and Europe, and the land war — especially during the fall of Hong Kong in December 1941, and the Dieppe raid of August 1942. These campaigns were followed by the invasions of Sicily, in July 1943, and of the Italian mainland the following September (see Italian Campaign), all of which caused a steady drawdown of resources and recruits. The First World War had seen voluntary recruitment fail in late 1916 and conscription brought in the next year by Prime Minister Robert Borden. With this in mind, King demanded promises from his military leaders that they had enough men. They assured the Prime Minister that they did – until they did not. In October 1944, after the attritional summer battles of D-Day and the Normandy campaign, and later, the liberation of France, Belgium, and part of the Netherlands, the Canadian Army faced a shortage of infantrymen.

King had spent the war desperate to avoid another rift over manpower between English and French Canadians, as well as with labour unions and farmers (two groups that opposed conscription on account of feared labour shortages and a fear that the labouring classes would be targeted), but the lack of trained Canadian infantry in Europe and Italy was leading to unnecessary casualties in the field. King tried to find a compromise throughout late October with his minister of defence, J.L. Ralston, who demanded that conscription be brought in. With supporters lined up behind them, neither man budged. The divided Cabinet was on the verge of collapse.

King fired Ralston on 1 November, but there was no way forward and the country was coming apart at the seams. Much of English Canada demanded conscription, while French Canada urged King to stick to his earlier promise. King vowed to stand his ground, but when it looked like his government might fall, he switched his mind and on 22 November ordered limited conscription. About 13,000 unwilling soldiers — originally conscripted only for home defence — were sent overseas. More than 2,400 of them made it to the front. King survived the crisis, although he was condemned for his actions. Québec, while angry, felt that King had done his best to hold off the more fervent English Canadians. Unity was damaged but not as severely as during the First World War.

Re-Election

King led the country through the war and oversaw one of the most effective Cabinets in Canadian history. By scrambling and compromising, King eased tensions. He emerged from the six years of war battered and tired, but he summoned enough energy to win another federal election, in June 1945. His mistakes during the war were few in number and never fatal to the nation. King also set Canada on a prosperous road to peace by enacting the generous Veterans Charter, which provided benefits for returning service personnel. He also instigated the Family Allowance Act, known informally as the Baby Bonus, which paid families a monthly stipend for each child. Canada’s gross national product rose from $5.6 billion in 1939 to $11.8 billion by war’s end. A wealthy Canada was ready to purchase homes and household goods after the war, and the Canadian economy boomed.

Some 1,080,000 Canadians enlisted in the armed services from a population of 11.5 million citizens. The army had risen to half a million troops, and its two corps had fought in multiple theatres of war. The air force reached a peak of 215,000 men and women, many of them airmen forming bomber squadrons in No. 6 Group, Bomber Command. The navy expanded to close to 100,000 sailors and was, for a time, one of the largest navies in the world.The merchant navy also contributed to victory by carrying crucial war supplies across the Atlantic. But Canada paid a high price for its service, losing close to 44,000 killed during the war from among all the service arms and the merchant marine. Despite the grief and loss, Canada emerged from the conflict as a strong middle power.

Reputation

King has come off badly in history. He is seen as a waffling weirdo due to his belief in the supernatural, and for partaking in seances. His reputational wounds were partially self-inflicted. King kept diaries for more than 50 years, which amount to more than 30,000 pages. They are the most important personal documents ever created by a Canadian, revealing insights into half a century of politics, two world wars, and the emergence of modern Canada. But, for King, keeping diaries was also cathartic, and so they contain his fears, worries, self-indulgences, waspish comments, and all manner of unflattering portraits of himself and others. King should not be judged by these records, but by his actions and accomplishments, which remain among the most important in all of Canadian history.

King believed that his greatest success as a wartime leader was what he prevented – the runaway passions of English Canada fired up to do anything in the war, as had been the case during the First World War. The scars of the first conscription battle in 1917 had not healed by the Second World War, and a second battle over manpower might have torn the country apart. King protected Québec from being abused and alienated for its lesser contributions to the cause of victory in the Second World War. And he did far more as Canada’s war leader.King oversaw the greatest mobilization of Canadians ever in the history of the nation. His leadership style of compromise served the country well, even if it was unglamorous and unheroic. “My first duty is to Canada,” wrote King during the war. “Keep our country united.” He succeeded in doing so in a war of utter necessity for humanity.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom