Wolastoqiyik (also Welastekwewiyik or Welustuk; pronounced wool-las-two-wi-ig), meaning “people of the beautiful river” in their language, have long resided along the Saint John River in New Brunswick and Maine, and the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. Historically, the Europeans referred to the Wolastoqiyik by a Mi’kmaq word, Maliseet (or Malecite), roughly translating to English as “broken talkers.” The name indicates that, according to the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqiyik language is a “broken” version of their own. Today, there are Wolastoqiyik communities in Quebec and the Maritimes as well as in Maine. In the 2016 census, 7,635 people identified as having Wolastoqiyik ancestry.

Population and Territory

The Wolastoqiyik have always lived in the Saint John River valley in New Brunswick and Maine, upward toward the St. Lawrence River in Quebec and westward into present-day Aroostook County, Maine. The traditional lands and resources of the Wolastoqiyik were bounded by their allies: the Mi’kmaq to the east; and the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot to the west.

The arrival of European settlers in the 1700s and 1800s curtailed the Wolastoqiyik’s agricultural territory on the river. During the 19th century, the colonial government created reserves for the Wolastoqiyik at Madawaska, Oromocto (Welamukotuk), Fredericton, Kingsclear, Woodstock, Tobique (Neqotkuk) and Viger (Wolastoqiyik Wahsipekuk). Since then, Wolastoqiyik bands have filed various land claims, some of which have been recognized by federal and provincial governments, such as the Tobique (Neqotkuk) 1892 land surrender (settled in September 2016) and the Madawaska Maliseet Canadian Pacific Railway Specific Claim (settled in 2008). (See also Indigenous Land Claims and Indigenous Territory.)

In the 2016 census, 7,635 people identified as having Wolastoqiyik ancestry. The total registered populations of Wolastoqiyik First Nations in Canada as of July 2018 are: Wolastoqiyik Wahsipekuk (Viger) (1,200), Kingsclear (1,042), Oromocto (Welamukotuk) (707), Madawaska (374), Saint Mary’s Wolastoqiyik (1,927), Tobique (Neqotkuk) (2,479) and Woodstock (1,074).

Pre-contact Life

Historically, the Wolastoqiyik were hunters and fishers, but they eventually also cultivated maize (corn), beans, squash and tobacco. To supplement their diet, women picked nuts, berries and fruits.

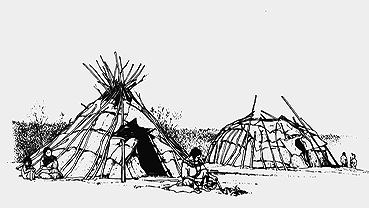

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Wolastoqiyik lived in wigwams in walled villages and used natural products, such as wood, stone and ceramics to make tools, canoes, weapons and everyday utensils. (See alsoArchitectural History of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Society and Culture

Wolastoqiyik bands were governed by one or more chiefs who sat on a tribal council that also included representatives of each family. As a community, the Wolastoqiyik were also members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, a group of Algonquian-speaking nations. Together, they stood united against the Five (and later Six) Nations Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) that threatened their territory and way of life. The Wabanaki Confederacy is still active today. (See also Abenaki.)

The Wolastoqiyik have a rich cultural heritage, similar to that of the Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq and Penobscot. Well-known for their artistry — including carving, quillwork, beadwork and basket-weaving — the Wolastoqiyik have created priceless pieces that speak to their history, spirituality and culture. Drumming is another important element of Wolastoqiyik culture. Used at a variety of ceremonies and celebrations, the music of the drum unites the community.

Language

The Wolastoqiyik language (still often referred to as Maliseet or Malecite) is considered part of the Eastern Algonquian language family, which also includes the languages of the Mi’kmaq, Abenaki (in Quebec), and Passamaquoddy and Penobscot (in Maine). The Wolastoqiyik and Passamaquoddy languages are very similar, with minor differences in vocabulary, pronunciation and accent; consequently, their languages are often collectively referred to as Maliseet-Passamaquoddy.

According to Statistics Canada (2016), there are about 350 Malecite (Wolastoqiyik) speakers in Canada who identify the language as their mother tongue. In the 2001 census, that number was higher (825), demonstrating a decline in the language. Wolastoqiyik communities are working to preserve and promote their endangered language through various initiatives, including a program of scholarship on the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language at the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre at the University of New Brunswick in collaboration with the native speakers.

Religion and Spirituality

Although missionaries converted many Wolastoqiyik peoples to Christianity in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Wolastoqiyik have retained their Indigenous spirituality. Traditional religious and spiritual customs include smudging (the burning of sweetgrass to cleanse the spirit), healing rituals and rites of passage ceremonies, among others. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Origin Stories

Wolastoqiyik origin stories tell the tale of Gici Niwaskw, the “Great Spirit” or Creator. Sometimes referred to as Weli-Niwesqit or Woli-Niwesqit — meaning “Good Spirit” in Maliseet-Passamaquoddy — the Creator is a benevolent and abstract being, who does not directly interact with humans. As in other Algonquian tales, the Great Spirit in Wolastoqiyik stories is rarely personified, and oral legends did not assign the Creator a gender. While Gici Niwaskw is said to have created the entire world, the details of maintaining and transforming or taming the landscape was given to the cultural hero, Gluskabe.

Gluskabe (Glooscap or Klusklap) figures importantly in many Wabanaki and Wolastoqiyik tales. There are various versions of the story, depending on the nation. According to most Wolastoqiyik tales, Gluskabe is not a god, but a hero and a trickster who had supernatural powers and used them to manipulate the world around it, making it more habitable for the humans. For example, he tempered the winds, tamed wild animals and managed the waters. In some Wolastoqiyik legends, Gluskabe’s older, but physically smaller, brother Mikumwesu accompanies him on his adventures. The stories of Gluskabe and other cultural figures, including his grandmother, evil twin brother and more, have been passed down from generation to generation, often through oral tradition.

Colonial History

Contact with European fishermen and fur traders in the early 17th century developed into a stable relationship which lasted for nearly 100 years. (See also Fur Trade.) Fort La Tour, built on the Saint John River in the early 1600s, became a centre for trade and cultural exchange. Despite devastating population losses to European diseases, the Wolastoqiyik held on to coastal and river locations for hunting, fishing and gathering, and concentrated along river valleys for trapping.

As hostilities between the French and English in Quebec and Port-Royal intensified during the mid- to late-1600s, sporadic fighting and raiding increased on the lower Saint John. These conflicts hampered the success of the eastern fur trade. To ease the economic burden during this time, Wolastoqiyik women began to farm and raise crops which previously had been grown only south of Wolastoqiyik territory. Men continued to hunt, though with limited success, but they proved useful military allies to the French against the English during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. (See also Iroquois Wars.) Intermarriage between French settlers and Wolastoqiyik only reinforced their alliance against the English.

In order to encourage better relations, the British Crown signed treaties of peace and friendship with the Maliseet, as well as with the Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy, between 1725 and 1779. The agreements also guaranteed Indigenous right to trade without hindrance, the right to fish and hunt in their customary manner, and the right to receive annual supplies of food, provisions and ammunition from the Crown. (See also Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

With the gradual cessation of hostilities in the first quarter of the 18th century, and with the beaver supply severely diminished, there was little possibility of a return to traditional lifeways. Indigenous agriculture on the river was curtailed by the coming of European settlers; all the farmland along the Saint John River, previously occupied by Wolastoqiyik, was taken, thereby displacing the Wolastoqiyik. After years of being pushed off their traditional territories, the Wolastoqiyik were forced onto reserves during the 19th century.

Aboriginal Title Claim

In October 2020, six Wolastoqiyik communities announced a title claim to lands along the Saint John River. Indigenous descendants of the Peace and Friendship Treaties argue their ancestors never surrendered these lands. The claim covers roughly half of New Brunswick. (See also Aboriginal Title.)

Contemporary Life

The Wolastoqiyik communities in Canada are Wolastoqiyik Wahsipekuk (Viger), Madawaska, Kingsclear, Oromocto (Welamukotuk), Saint Mary’s Wolastoqiyik, Tobique (Neqotkuk) and Woodstock. There is also a community in Maine: the Houlton Band. However, there is no one organization that represents the Wolastoqiyik politically.

Wolastoqiyik First Nations actively pursue land claims, manage resource allocation (fuel, forestry, fishing and the like), participate in organizations for pan-Indigenous causes and support on-reserve businesses, including retail stores, gaming centres, gas stations and more.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom