Marie de l’Incarnation, born Marie Guyart, founder of the religious order of the Ursulines in Canada, mystic and writer (born 28 October 1599 in Tours, France; died 30 April 1672 in Quebec City). Her writings are among the most important accounts of the founding of the colony of New France and the establishment of the Roman Catholic Church in the Americas. Her work as a teacher helped to lay the foundations for formal education in Canada.

Portrait of Marie de l'Incarnation. Hugues Pommier - André Vachon, Victorin Chabot and André Desrosiers, "Rêves d'empire. Le Canada avant 1700, coll. Les documents de notre histoire", Public Services and Procurement Canada, 1982.

Spiritual Calling in Childhood

The daughter of master baker Florent Guyart and Jeanne Michelet, Marie Guyart received a profoundly Catholic education and sound instruction. In the family bakery, she learned the basics of managing a business.

From childhood, Marie showed signs of an unusual spiritual life, marked by mystical visions of Jesus. She said that at age 7, she had received a spiritual calling to devote herself entirely to God. She therefore gradually stopped playing with children her own age and instead spent her time reading devotional books and meditating.

Wife, Mother and Businesswoman

At age 14, Marie expressed her wish to enter the convent of the Benedictine Nuns. But her parents encouraged her to marry instead, and she was wed to Claude Martin, a master silk worker. The marriage was difficult: for one thing, Marie’s mother-in-law was jealous of her; for another, despite the devotion that Marie showed toward her husband, her spiritual commitment was her first concern. He died in 1619, after just two years of marriage, leaving her with a six-month-old son, Claude. Marie took care of liquidating the family business, which had gone bankrupt.

After her husband died, Marie put her son in the care of a wet-nurse and went back to live in her parents’ home. She spent a year living on the top floor like a recluse and devoting much of her time to meditation and prayer while doing needlework to earn a living. Her family encouraged her to remarry, but instead she chose to take a vow of chastity. On 24 March 1620, she had a mystical and emotional “conversion” experience. She decided to withdraw from the world, but her sister and her brother-in-law asked her to stay and help them rebuild their failing transportation business. She agreed, and took on many responsibilities, including administration, the handling of goods and the health of the company’s employees. The business prospered, but Marie continued to experience visions of spiritual marriage to God. She spent her free time in meditation, prayer and penitence. She also took her son back, but refrained from showing him too much affection, so as to prepare him for the separation that she knew would come when she entered religious orders.

Entry into the Ursulines

In 1631, despite the considerable pain that it caused her to leave her 11-year-old son behind with her sister, Marie Guyart entered the cloister of the Ursulines in Tours and took the name of Marie de l’Incarnation. Total separation from her family and the outside world was one of the conditions for entering the order—in other words, she had had to choose between God and her son. She took her vows in 1633 and taught Christian doctrine for the next six years. At age 34 or 35, she had what she believed to be an out-of-body experience, in which she saw her spirit travelling to various countries where there were souls to convert, including Canada. Her visions, together with her reading of the Jesuit Relations, accounts of life in Canada by missionaries from the Society of Jesus, convinced her that God was calling her to Canada.

Missionary in New France

Along with two other Ursuline nuns and Mme de la Peltrie, the patron of the Ursuline order in New France, Marie de l’Incarnation landed in Quebec City on 1 August 1639. There she founded a convent and the first school for girls, in the Lower Town. In 1642, the Ursulines moved into a new stone monastery in the Upper Town. There Marie de l’Incarnation zealously dedicated herself to educating French and Indigenous girls. From her earliest years in Canada, she worked doggedly to convert Indigenous people to the Catholic religion and French culture—that is, to assimilate them. The education that the Ursulines provided was designed to make Indigenous girls give up their nomadic lifestyle, adopt the Catholic faith and start wearing French-style clothing. The purpose of this education was to get the girls to abandon their original culture and become perfect prospective brides for French men. To facilitate this assimilation, the Ursulines did show some flexibility with regard to the girls’ language and diet. But in 1668, Marie de l’Incarnation acknowledged that her efforts with Indigenous girls had failed. From then on, the Ursulines concentrated on educating the daughters of the French colonists instead.

In addition to numerous theological and spiritual treatises, Marie de l’Incarnation wrote a catechism in Iroquois, as well as Algonquin and Iroquois dictionaries (see Indigenous Languages in Canada). She also kept abreast of public affairs. Though cloistered, she received many illustrious visitors, such as the first bishop of Quebec City, François de Laval.

In 1646, together with the Jesuit Jérôme Lalemant, Marie de l’Incarnation wrote a constitution to guide the spiritual lives of the Ursulines in New France. This consitution adapted the rules of the Ursulines in France to the realities of their lives and mission in North America.

In 1650, a fire destroyed the Ursuline monastery when one of the sisters forgot burning coals under a dough trough. No lives were lost, but the destruction was total. Only the barns remained intact. The sisters took advantage of the reconstruction to expand the monastery.

Writer

Marie de l’Incarnation’s written works constitute one of the largest collections of personal documents from the early years of French colonization. Over 277 of her handwritten letters have been preserved to the present day, including 30 years of correspondence with her son Claude, who became a Benedictine monk. The main subject of these writings is spirituality, but they also contain numerous observations on the growth of New France. At age 55, Marie de l’Incarnation wrote an autobiography, Relation de 1654—actually not a chronology of her life, but rather a sort of apology to explain to her son the reasons that she abandoned him. Claude published this Relation, adding to it some excerpt from an earlier autobiography that his mother had written in 1633. He subsequently published 221 letters of correspondence in an anthology entitled Écrits spirituels et historiques.

Legacy and Canonization

Marie de l’Incarnation died in Quebec City at the age of 72. After her death, the Ursulines went on with her work in Trois-Rivières, where they founded a monastery in 1697. They even ventured as far as Lousiana, where they founded a school for girls in New Orleans in 1727. Their convent, rebuilt in 1752, is one of the rare buildings of the French Regime to have survived in Louisiana.

In 1980, Marie de l’Incarnation, François de Laval and José de Anchieta (also known as the Apostle of Brazil) were officially beatified by Pope John Paul II (beatification is the final step before canonization and sainthood). On 3 April 2014, Pope Francis proclaimed all three of them saints by an exceptional procedure known as equipollent or equivalent canonization, in which someone is canonized without having performed a miracle. Their canonization was celebrated at the Thanksiving Mass in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome on 12 October 2014. Cardinal Gérald Cyprien Lacroix, Archbishop of Quebec, headed the Quebec delegation that came to attend the ceremony.

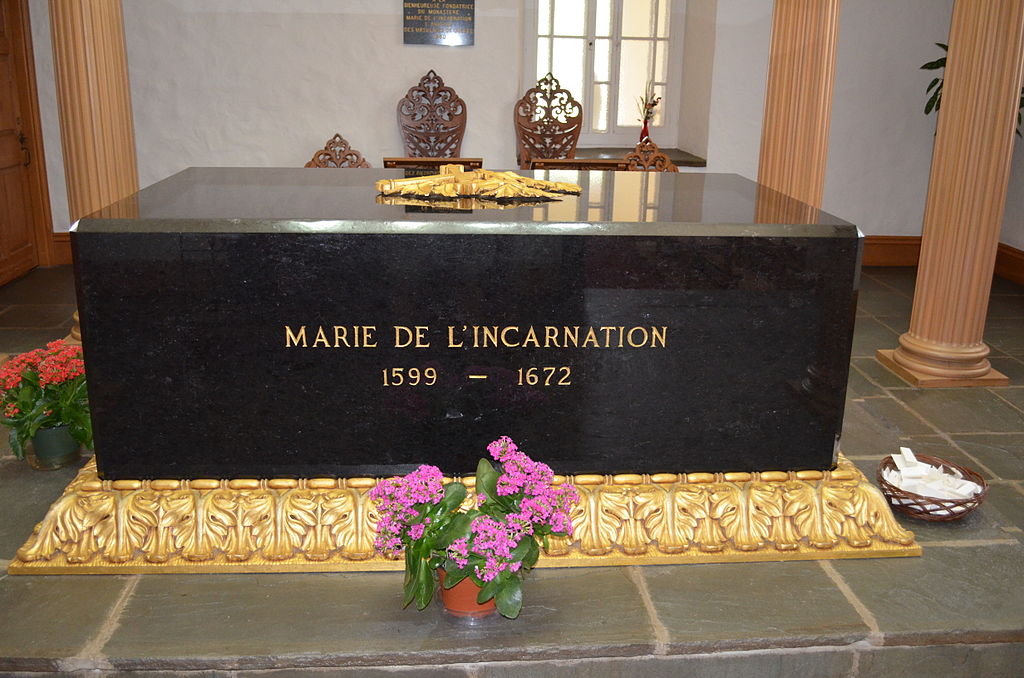

The tomb of Marie de l'Incarnation in a room of the Ursulines of Quebec chapel.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom