The Maroons of Jamaica

The Maroons fought to maintain their freedom in Jamaica, where they had established several independent communities as early as the mid-1600s. In 1738–1739, after 84 years of almost continuous warfare, the first series of Maroon wars ended and a peace treaty was negotiated with the British. In peace, in a seeming paradox, the Maroons proved to be useful allies of the English planters, acting as slave catchers and as willing volunteers in the suppression of the occasional slave rebellion.

In 1795, the Trelawny Town Maroons, one of five major Maroon communities in Jamaica, initiated an uprising that became the Second Maroon War. The relationship between the government and the local Maroon community often depended on the ability of the local leadership and the government representative in the village to get along. In Trelawny Town, the relationship soured and this, combined with a variety of pent-up frustrations, caused the Maroons to oust their superintendent, desert their community and open hostilities.

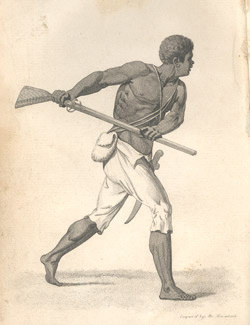

Secure in their hidden places in the Cockpit Country of central Jamaica, Trelawny Maroons engaged in guerilla warfare against government forces and raided nearby plantations. Although they had able leaders, including Montague James, Leonard Parkinson and James Palmer, the Trelawny Maroons did not prevail. Other Maroon communities did not join them in their uprising, their supplies began to run low and measles began to spread, and they were outnumbered and outgunned by government forces led by General George Walpole. The Maroons agreed to a truce on 21 December 1795. By March 1796, the conflict was over.

Claiming that the terms of the treaty were not fully met, the government of Jamaica determined to exile the Trelawny Maroons. By happenstance, the British Navy had a number of largely empty transport ships, under convoy protection, due to leave Jamaica. Jamaican authorities had discussed various destinations for the exiled Trelawny Maroons but the closest British port the transport fleet would pass was Halifax, the 47-year-old capital of the colony of Nova Scotia. Accordingly, without consultation with Governor Sir John Wentworth or his government (see Council of Twelve), they decided that Halifax would be at least the temporary destination of the Maroons. Jamaica provided a grant of £25,000 to pay their expenses and sent administrative officials and Doctor John Oxley, a surgeon, to travel with them.

Arrival in Halifax, Nova Scotia

On 21 and 22 July 1796, the Dover, Mary and Ann landed in Halifax Harbour, carrying between 550 and 600 Maroon men, women and children. The government of Nova Scotia was left to determine their future. Prince Edward Augustus (later Duke of Kent), who had reviewed the Maroon men on shipboard, employed them to work on his refortification of Citadel Hill (see Halifax Citadel). Eventually, with the permission of the British authorities, Wentworth decided to settle the Maroons in Nova Scotia. Some of the land and farms that had been left vacant by the emigration of the Black Loyalists in 1792 were available in Preston (see also Black Canadians). Additional houses were built, a schoolmaster and clergyman employed, provisions were provided, and the Maroons were expected to become peaceful farmers. In acknowledgement of the Maroons’ military reputation, and because the government feared a French invasion, the Maroons were organized into a militia company. Their officers were among the leaders of the 1795 rebellion in Jamaica and all were battle-hardened.

Settlement Challenges

The settlement effort was not a happy venture. The winters of 1796 and 1797 were longer and colder than anything the Maroons had experienced. The snow was deep and the lakes and rivers frozen. Many did not like it and some, including a number of the leaders, decided then that they would arrange their own future. In protest of their condition and lack of familiar foods, the Maroons on occasion would withdraw the boys from school (the girls did not attend) and refuse to attend church. The Maroons were not Christian, and they maintained their faith system (which included polygamy) and brought their own religion and customs. The Maroon school attracted visitors. One was Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, who became in 1830 the King of France. Wentworth also sent examples of the students’ work to Britain to demonstrate their accomplishment. While the distribution of long-delayed clothing and supplies reversed the protests in the short term, it did not affect the Maroons’ determination to leave.

Petitioning

Disputes arose within the Maroon community at Preston, or Maroon Town as it was also called. The majority wanted to leave Nova Scotia and return to Jamaica, but that was not allowed by the island government. Otherwise, they were willing to go anywhere that was warmer. They petitioned the government in April 1798, saying that “the Maroon cannot exist where the pineapple is not.” At the same time, they secretly communicated with General Walpole, by then a member of the British parliament, for support. They also sent a representative to London to carry petitions and to exert influence on their behalf.

Others, however, decided to make the best of the situation in Nova Scotia. Led by war hero James Palmer, they asked the authorities to be settled apart from the main group. They were accommodated by the creation of a second Maroon community at Boydville, located in the area that today is called Maroon Hill. While the Preston Maroons petitioned for removal, those at Boydville requested sheep, seed grain and a cow or two. Despite the fact the Preston Maroons did not want to farm, they were not idle. All worked on the road and for local farmers and merchants. The women and children supplied the Halifax market with berries, eggs and poultry in addition to pigs, brooms and baskets. In 1800, the men were employed digging the foundation for the new Government House, still the official residence of the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia. The Maroons generally worked beside soldiers and other White labourers and always commanded equal pay.

Departure from Nova Scotia

The story of the Maroons in Nova Scotia is brief. They arrived in 1796 and left in 1800. Those who petitioned to leave won the day. The British authorities, over the objection of Wentworth, decided that all of the Maroons would go, including those at Boydville. They were to leave in 1799 but it was over a year later before transport was arranged and all the details were finalized. Wentworth, who had been criticized for settling the Maroons as a community rather than scattering them throughout the province, continued to risk his relationship with the British authorities by ordering extra provisions for the Maroons to use during their voyage. Finally, on 7 August 1800, 551 Maroon men, women and children sailed out of Halifax Harbour on board the HMS Asia, bound for Freetown, Sierra Leone, in Western Africa. They arrived safely on 30 September 1800 and volunteered to support the government against the 1792 Black Loyalist settlers who had rebelled. In Freetown, they perpetuated the memory of Jamaica by the creation of Trelawny Street, and oral history maintains that some of their descendants squared the circle by the mid-1800s and returned to their unforgotten island homeland.

Legacy

Tradition insists that not all of the Trelawny Town Maroons left Nova Scotia on the Asia. In 1817, a Census of the Black community of Tracadie in Guysborough mentioned several descendants of the Maroons. But, other than their contribution to the bloodlines of Nova Scotia, their name has been perpetuated in Maroon Hill and by reference to the Maroon Bastion (long since replaced) at Citadel Hill. In 2000, the Nova Scotia Department of Education introduced a high school program focused on African-Canadian heritage and history (as part of the Social Studies and English courses). But perhaps the most important, long-lasting influence of the Maroons is the one that is the most difficult to measure. For sure, they contributed to the construction of African Nova Scotian identity.

See also Black history in Canada Collection

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom