This article was originally published in Maclean's Magazine on April 8, 1996

In the fall of 1954, a floatplane landed briefly near Repulse Bay, a small village on the northern end of Hudson Bay. When it took off again, the plane carried away half a dozen Inuit children, including six-year-old Michael Kusugak. The children were flown to a residential school in Chesterfield Inlet, 400 km to the south, run by the local Roman Catholic mission. The teachers, most of them nuns who spoke only English or French, ran a strict operation and did not allow the youngsters to speak in their own language, Inuktitut. "The only thing I remember about that year," says Kusugak, now 47 and an award-winning children's author, "is that I sat in the back of the class and cried the whole time." After returning to Repulse Bay for the summer, Kusugak was determined to stay put. So when the plane came back in the fall, he recalls, "I ran away and hid in the hills until I saw it fly away, then I went home." Adds Kusugak, with a wry smile: "I played hooky for an entire year."

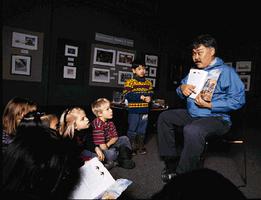

These days, the former truant spends about three months of each year in schools, libraries and museums across Canada, entertaining and delighting children who are not much older than he was when he headed for the hills. During such appearances, Kusugak reads from his four books, including A Promise Is a Promise, co-authored by KidLit superstar Robert Munsch, which has sold more than 200,000 copies since its publication in 1988. But he also plays traditional Inuit string games, recounts legends that he heard as a child, and talks about the life he once lived, travelling with his parents by dog team in search of the whales, seals and caribou that spelled the difference between starvation and survival. Like his books, which weave together real and imagined stories from the Arctic, the storytelling sessions are Kusugak's way of helping to preserve and explain a culture that is under siege. "We [the Inuit] have lost so much to television and videos," he told Maclean's during a recent interview. "Everything seems to come from Hollywood these days. I want to put back a little something so that the culture is not completely lost."

Kusugak's own life is a study in the contrasts that the Inuit have experienced over the past half-century - and a positive example of how to survive, and even thrive, while straddling two very different worlds. The eldest of 12 children, he was born in a sod hut near Repulse Bay and spent the first six years of his life in the nomadic tradition of the Inuit. He now looks back on that time with a mixture of nostalgia and pragmatic detachment. On the one hand, he says, "it was a really wonderful time to be a kid. Everyone told stories. And then there were all the legends of the Inuit that were told to put us to sleep at night. We got to listen to the most wonderful stories in the world." On the other hand, it was an often harsh existence, with survival depending on how good a hunter you were.

To illustrate that point, Kusugak tells a story his father told him as a child. "He said that when he was a young man with a young wife he was sitting in this igloo in Repulse Bay when a man and his son came to visit," recounts Kusugak. "And the man said, 'Why is your baby crying?' And my father said, 'Well, I was out hunting and I didn't get anything and so the baby has no milk.' And the man said, 'Why didn't you tell me?' So he dispatched his son to their igloo to get some food. And my father said it was the first time in many days that the family had eaten, and of course his wife got some milk in her breasts to feed the baby, and that baby was me." Kusugak smiles broadly. "I thought that was kind of a neat story," he says.

After his year of truancy, Kusugak spent another three years at Chesterfield Inlet, followed by stints at residential schools in Yellowknife and Churchill, Man. He spent each summer in the Hudson Bay community of Rankin Inlet, where his parents moved in 1960 and where he still lives today with his wife, Sandy, an assistant to Liberal MP Jack Anawak (Nunatsiaq), and their four sons: Geoffrey, 20, Benjamin, 18, Nathaniel, 13, and Graham, 7. Kusugak spent his high-school years in Saskatoon, where he lived with Robert Williamson, an anthropologist who was a friend of the Kusugak family from the years he spent doing research in the Arctic. Williamson, now a professor at the University of Saskatchewan, became Kusugak's foster father. He recalls the teenage Kusugak as a "very bright, very charming, very lively-minded young fellow." He also had a strong creative streak, playing guitar in a local pop-music band, reading voraciously, and writing short stories and well-crafted essays. "He had this combination," recalls Williamson, "of a sense of humor, sensitivity to language and people, and the ability to tell a story."

Despite those early creative instincts, Kusugak was a late bloomer as a writer. Dropping out after one year of university, he returned to Rankin Inlet, where, over the next two decades, he pursued a series of careers as a pilot, a potter and, eventually, a director of community programs at Arctic College. His return to writing came casually enough: as a father of young children, he says, he quickly tired of reading "Dr. Seuss and the like" and started to make up his own stories, many of them based on his boyhood memories. His kids, in turn, encouraged him to write them down. Then, in the mid-1980s, fate intervened in the person of Robert Munsch, the Guelph, Ont., children's author who stayed at Kusugak's home during a reading tour of the North. As well as taking him fishing and hunting, Kusugak began to tell Munsch some Inuit fairy tales. Intrigued, Munsch told him to send down samples of his writing.

The first story that Kusugak submitted eventually became A Promise Is a Promise, published by Toronto-based Annick Press in 1988. It deals with Qallupilluit, mythical creatures that live under the sea ice, and a little girl who defies them. To discourage children from the dangerous game of jumping from ice floe to ice floe during spring breakup, Inuit parents told them about Qallupilluit, which, if they saw kids playing on the ice, would grab them, take them under the ice and never bring them back. While Kusugak's original version was rejected by Annick, he and Munsch reworked it extensively into a book that has gone on to be a phenomenal best-seller. What appealed to him about the tale, Munsch told Maclean's, is that "it jumps cultures. All parents deal with dangerous situations and how they can keep their children safe."

Kusugak followed up two years later with his first solo effort, Baseball Bats for Christmas. It is based on a true story that took place in Repulse Bay during the year that Kusugak played hooky. One day shortly before Christmas, a bush pilot dropped off a half-dozen unsolicited Christmas trees. Living on the treeless tundra, young Michael and his playmates were baffled by what to do with what they called the "standing-ups." Then, one of the boys had a bright idea: by chopping away the spindly branches, he was able to fashion a round, firm bat from the trunk. The pilot, he exclaimed, had "brought us baseball bats for Christmas."

Kusugak's next two books were less autobiographical but equally rooted in the Arctic. Hide and Sneak (1992) is about a little girl who outwits another mythic creature, an Ijiraq, which is said to hide children on the tundra so that they can never be found again. Northern Lights: The Soccer Trails (1993) is the moving story of how a girl whose mother has died is told that the shimmering northern lights are really the reflection of the souls of dead people chasing a soccer ball - and who one night recognizes her mother as one of those celestial soccer players. All four books are beautifully illustrated by Vladyana Krykorka, a Prague-born, Toronto-based freelance artist who has visited Kusugak several times in Rankin Inlet to sketch and photograph the unique northern landscape.

Kusugak and Krykorka are now putting the finishing touches on a counting book, expected out in the fall, that will feature such northern animals as polar bears, lemmings and bowhead whales. But Kusugak, who has been working full time as a writer for the past three years, is immersed in other projects as well. An avid reader of classical literature (his favorite author is Geoffrey Chaucer, after whom he named his first son), he is in the midst of writing his first book for adults. "It's a story about a young man and his old uncle," he says. "The young man, who has grown up down south, wants to go back to his roots. The uncle doesn't know any English; he's grown up in the North, but has always been intrigued by the things he sees about the South on TV. And then the two of them get together and feed off each other."

It is perhaps inevitable that Kusugak - who in his spare time still fashions ice chisels and builds sleds - should be writing about bridging cultures. Despite all the time he spent being educated in southern ways, he is, according to his former foster father, "very deeply rooted in the Inuit culture." Adds Williamson: "He has maintained a respect and good memory for all he has drawn from that culture. He has enriched himself and his family by it, and now he's enriching the entire country."

Maclean's April 8, 1996

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom