Muskeg (from Cree maskek and Ojibwe mashkiig, meaning “grassy bog”) is a type of northern landscape characterized by a wet environment, vegetation and peat deposits. Chiefly used in North America, the term muskeg escapes precise scientific definition. It encompasses various types of wetlands found in the boreal zone, including bogs, fens, swamps and mires. In Canada, muskeg and other peatlands cover up to 1.2 million km2, or 12 per cent of the country’s surface.

How Does Muskeg Form?

Most muskeg and peatlands in Canada are less than 10,000 years old and occur in areas covered by the last glaciation. As glaciers retreated, their meltwater created large, flat plains, as well as lakes and depressions. Muskeg has developed on such landforms, where permafrost is common and where water drainage from the top layer of soil is poor. Dead plants decompose slowly in the wet, cool and acidic environment, forming a moist layer of spongy earth called peat.

Did you know?

Among the most common muskeg plants are spongy Sphagnum mosses, which can hold up to 30 times their own weight in water.

Muskeg may cover large areas (e.g., the Hudson Bay Lowland) or occur in small, isolated pockets. It produces peat deposits that can be up to several metres thick. Scientists can use remote sensing to detect different types of muskeg by their particular vegetation, as well as by patterns in the movement and distribution of water (see also Hydrology).

Why Is Muskeg Important?

Muskeg provides habitat for various species. Birds breed and nest in these wetlands, which are also home to many insects. Muskeg ecosystems support the threatened woodland caribou, beavers, muskrats, voles, bats and other mammals.

Plant species typical of muskeg environments include Sphagnum mosses, sedges, grasses, shrubs (e.g., leatherleaf and Labrador tea) and stunted coniferous trees (e.g., black spruce and tamarack).

The world’s peat deposits contain billions of tonnes of carbon from decomposed organic material. When muskeg landscapes remain intact, they store carbon in the earth and prevent it from entering the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and methane. These greenhouse gases are released when muskeg is drained, deforested, burned or degraded, whether by human activity or by natural processes. Conserving muskeg and peatlands therefore helps counteract climate change.

Peat is harvested across Canada for export and sale as a gardening soil. This industry is regulated by federal, provincial and territorial policies that limit its environmental impact. Peat is also used to clean up oil spills and to filter air and wastewater. Raw materials used in some chemical products such as resins and waxes are derived from peat, as are some skin and spa therapy products.

Engineering Challenges

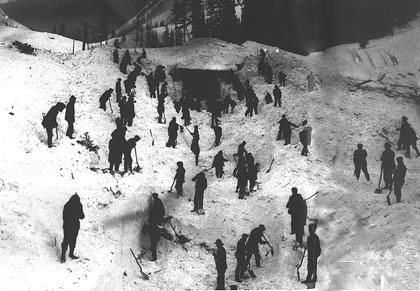

Roads, pipelines and other projects can be difficult to build through muskeg. Structures can settle

and sink in its spongy softness. Building on sensitive permafrost can also change the temperature of the ground and cause frost heave, a swelling of the ground that can damage human-made

structures. Additionally, the acidic water in muskeg can corrode metals and concrete.

(See also Vegetation Regions.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom