Beothuk and Vikings

Beothuk people were among the first in North America to encounter Europeans, when Vikings settled in L’Anse aux Meadows around 1000 CE. The Vikings left after a few years. Europeans didn’t return until 1497 with John Cabot’s mapping expedition. Britain claimed the territory in 1583.

The Beothuk were destroyed by warfare and disease. (Shawnadithit, the last of the Beothuk, died in 1829.) By the mid-1800s, the European population of Newfoundland had reached 140,000. The colony was run by a British governor and an appointed council in the early 1800s. It received responsible government in 1855.

Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences, 1864

Newfoundland was not part of the Charlottetown Conference of September 1864, when leaders from Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada met to discuss Confederation. Conference organizers had assumed Newfoundland was not interested in a wider union. However, two of the colony’s officials did attend the Quebec Conference in October 1864. It was here that the details of Confederation were ironed out. (See Quebec Resolutions.) Newfoundland politicians Ambrose Shea and Frederic B.T. Carter went to Quebec City as observers rather than as voting delegates. They brought back positive impressions of Confederation, which were debated in the legislature in St. John's.

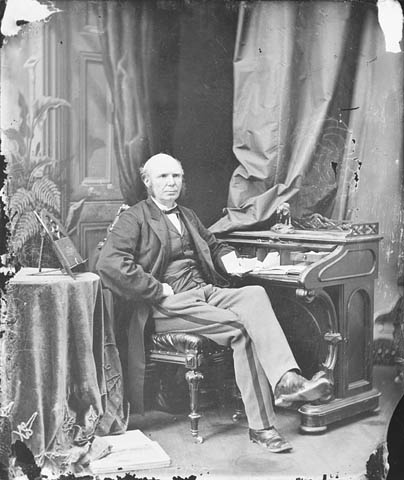

In Newfoundland, public opinion toward Confederation was mixed. Politician Charles Fox Bennett led the anti-French, anti-Confederation movement. (See also Confederation’s Opponents.) He warned of high taxes and conscription into Canadian wars. Despite his efforts, a pro-Confederation government won the Newfoundland election in 1865. However, the legislature also voted not to discuss the Quebec Resolutions. As a result, the colony did not send delegates to attend the London Conference. Newfoundland’s governor, Sir Anthony Musgrave, was invited to attend the first session of the Canadian Parliament in November 1867, but only as an observer.

Other Attempts to Join Confederation

The pro-Confederation government remained in power after 1867. Encouraged by Musgrave, the legislature continued to consider Confederation. By the summer of 1869, a deal was close to being completed. But Bennet and his anti-confederation allies stepped up their attacks and ensured that public sentiment was on their side. As Edith Fowke has observed, “Pro-Confederationists argued the advantages of lower prices for goods; Anti-Confederationists countered with the prospect of high taxes on fishermen’s boats and gear and played on Newfoundlanders’ pride in being Britain’s oldest overseas colony.” (See also “The Anti-Confederation Song”.) In the heated election of 1869, the anti-Confederation side won a decisive victory.

In the 1890s, the colony suffered a bank crash. By 1895, there was renewed interest in Confederation as a solution for Newfoundland’s financial troubles. But Canada offered less favourable financial terms than Newfoundland wanted, so no deal was reached. In fairness, the desire of Newfoundlanders to become Canadian had never been strong.

Commission Government, 1934–49

The First World War initially brought prosperity to Newfoundland. The colony used its new wealth to build roads and railways. It also sent a regiment to fight with the British. (See Battle of Beaumont-Hamel.) By the 1920s, however, Newfoundland was in debt. The Great Depression of the 1930s soon made the problem much worse. Facing bankruptcy, Newfoundland’s leaders suspended responsible government in 1934. They also accepted an unelected Commission Government directed by Britain.

Newfoundland became an important strategic armed forces base during the Second World War. This brought back prosperity thanks to American, British and Canadian military investment. By 1949, the colony had cleared its debts and enjoyed a $40-million surplus.

Confederation Debate, 1946–48

In 1946, an elected National Convention was created to examine the colony’s political future. It resulted in two years of vigorous debate over whether to continue with the Commission Government, join Canada, or seek a return to responsible government as an independent dominion.

A bitterly fought referendum campaign ensued. The Confederation side was led by Convention members F. Gordon Bradley and Joey Smallwood. They argued that joining Canada would raise living standards for Newfoundlanders. The Confederation option was also encouraged by Britain.

While the confederate campaign was well-organized, its opponents were divided. The Responsible Government League, led by Peter Cashin and supported by Roman Catholic archbishop Edward Patrick Roche, wanted a return to Newfoundland’s status in 1933, before the Commission Government. The Economic Union Party, led by Chesley Crosbie, supported responsible government but emphasized close economic ties with the United States.

In the referendum of 3 June 1948, the responsible government option received 44.6 percent of the vote. Confederation received 41.1 percent and the Commission Government option received 14.3 percent. However, a run-off vote was held on 22 July 1948 between responsible government and Confederation. In the final tally, Confederation received 78,323 votes (52.34 percent) and self-government got 71,344 (47.66 percent).

10th Province

Canada was eager to bring Newfoundland into Confederation. Some feared that the United States, with its large military presence there, would one day take possession of the territory.

Smallwood led a team to Ottawa to negotiate the terms of entry with Prime Minister Mackenzie King. The British and Canadian parliaments approved of the Terms of Union. The terms were incorporated by the British Parliament into the Dominion of Canada through the British North America Act, 1949. The Terms of Union also restored Newfoundland’s legislature and responsible government, which had been suspended since 1933.

Newfoundland became Canada’s 10th province on 31 March 1949. The first session of the legislature was held in St. John’s on 13 July 1949. Smallwood was elected its first premier. He and Sir Frederic B.T. Carter and Sir Ambrose Shea are considered the province’s Fathers of Confederation. In 2001, the province’s name was officially changed to Newfoundland and Labrador.

See also: Editorial: Newfoundland Joins Canada; Fathers of Confederation; Mothers of Confederation; Confederation: Collection; Confederation: Timeline; Newfoundland and Labrador; Newfoundland and Labrador: Timeline; Politics in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom