The northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) is a toothed whale found in the northern regions of the Atlantic Ocean. In Canadian waters, there are two populations: one off the coast of Nova Scotia, known as the Scotian shelf population, and the other off the coast of Labrador, known as the Baffin-Labrador population. The Scotian shelf population is endangered while the Baffin-Labrador population is considered “special concern” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. The northern bottlenose whale is the largest beaked whale in the North Atlantic. (See also Endangered Animals in Canada.)

Northern bottlenose whales swim in The Gully, off the shores of Nova Scotia. This population of northern bottlenose whales, known as the Scotian shelf population, is endangered.

("Northern bottlenose whales spyhopping" by Hilary Moors is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.)

Physical Description

Northern bottlenose whales are named as such due to their bottle-shaped beaks, which give them a dolphin-like appearance. They are much larger than most dolphins, however. The typical calf is 3.5 m long, while most adults grow to between 7 and 9 m and weigh 5 to 8 tonnes. Males are usually about 1 m and 1 to 2 tonnes longer and heavier than females. Their colour ranges from greenish brown or yellowish brown to chocolate brown, sometimes with gray-white patches and a whiter underbelly. They possess a large, protruding forehead called a melon. This melon tends to be larger and flatter for males, becoming whiter in older males. Despite being toothed whales, only one pair of teeth erupt through their gums, and usually only in males.

Distribution and Habitat

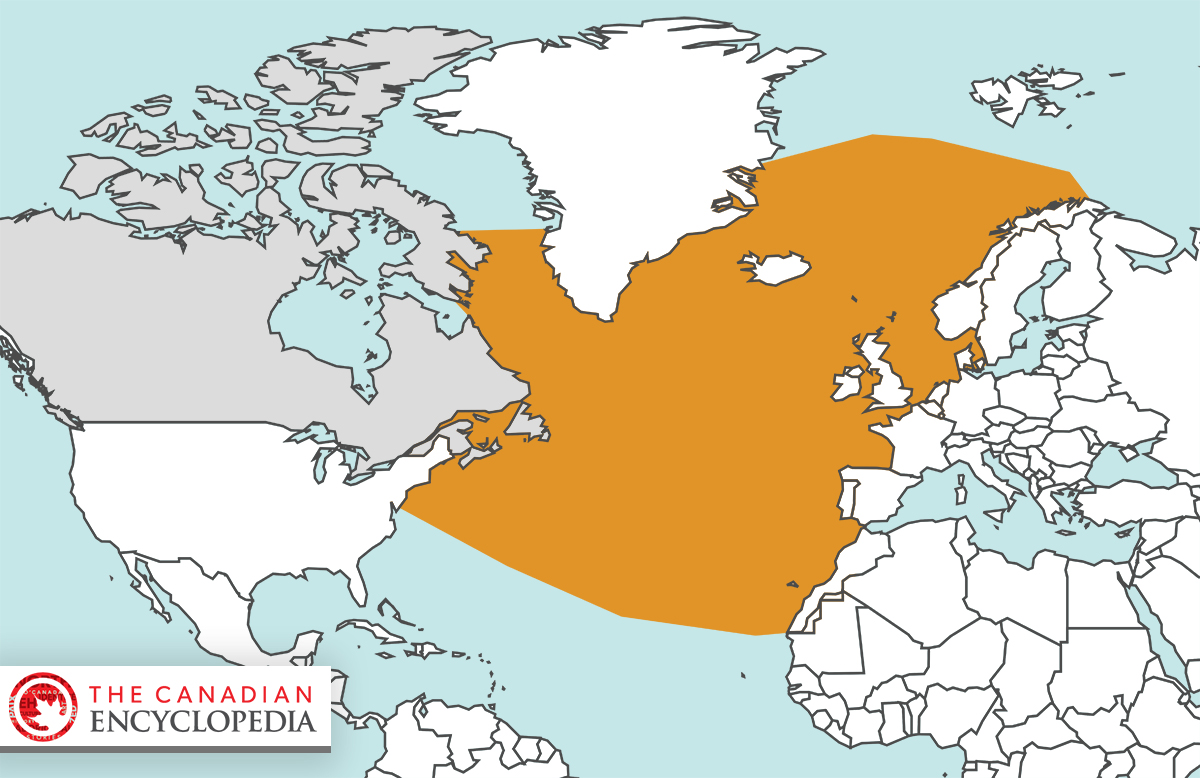

The northern bottlenose whale prefers deep waters. They are most commonly found in depths greater than 1,000 m — roughly twice the length of the CN Tower. Its range extends from North Atlantic polar ice all the way to the southern regions of New England and the Cape Verde Islands off the coast of Africa. Most individuals migrate south for winter within these limits. Its population is mostly concentrated in the following areas: off the coast of Nova Scotia, off the north coast of Labrador and into southern Baffin Bay, around Iceland, around Svalbard, and off Norway’s coast. Because of the whale’s concentrated population areas, deep diving behaviour and tendency to approach ships, it is difficult to estimate its numbers. By most assessments, there are between 15,000 and 40,000 individuals alive today.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Female northern bottlenose whales typically live up to 27 years and males to 37 years. Males reach sexual maturity roughly between the ages of 7 and 9, and females roughly between the ages of 8 and 13. The species is polygynous, which means a single male will associate with a group of females for reproduction. Mating season occurs in spring and early summer, with a 12-month gestation period. Females birth single calves, and wait 2 to 3 years between one and the next.

Behaviour

To feed itself, the northern bottlenose whale has been observed diving for over 90 minutes, to depths exceeding 2,000 m. Deep-water squid of the genus Gonatus make up most of its diet. It also feeds on various fish and benthic invertebrates. The whales emit ultrasonic clicks, which are amplified in their melons. It is believed that these sounds are used for echolocation of their prey. They also use low-intensity sounds, which may be for communication purposes. They typically associate in groups of about 4 to 20 individuals.

Northern bottlenose whales are usually curious about slow-moving or stationary ships and will approach them. They also tend to accompany and try to help any of their injured comrades. This has made them easy prey for hunters in the past.

Relationship to Humans

Hunting of northern bottlenose whales for oil, pet food and other animal feed was commonplace between 1850 and 1973. They were mostly hunted by Norwegians, but also the Scottish and British. Estimates are vague, but it is likely that at least 65,000 individuals were hunted during that period. In Canada, accounts of Indigenous peoples’ relationship to the whale are sparse. Some indicate that the Inuit of Hopedale, Labrador, consumed northern bottlenose whale, although it is unclear to what extent.

Since the early 1970s, commercial hunting has died out due to a combination of factors. The United Kingdom banned the import of the whale’s meat, while in Norway, cheaper sources of animal feed were found. Protests against commercial whaling also contributed. Only in the Faroe Islands, where two to five whales a year get stranded and cannot return to sea, is its consumption still allowed.

Threats

Even though the northern bottlenose whale is no longer hunted by humans, it still faces several threats. Its main predator is now the killer whale. Some individuals get entangled in fishnets, but the severity of this threat is generally deemed low or uncertain. Contaminants put into waterways by humans, such as PCBs, DDTs and oil spills, can also be dangerous (see Water Pollution). Studies of the whales’ blubber have mostly shown low levels of these chemicals so far, but effects are uncertain. Noise pollution may also be a serious threat. Since the northern bottlenose whale relies on sound for foraging, navigation and communication, noisy human activities can be disruptive to its functioning. These include navy sonar, military exercises, and oil and gas exploration. Primrose Field is a notable example. It lies about 5 km away from the main Scotian shelf population and contains petroleum reserves, currently untouched. If these reserves were extracted, however, the noise from the operation could significantly impact Scotian shelf northern bottlenose whales.

Conservation

Several authorities have stepped in with recommendations and regulations to protect the northern bottlenose whale. In 1977, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) classified the species as a provisional protected stock with zero catch limits, which means that no individuals can be hunted at all. Since 1984, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) forbids any international trade of northern bottlenose whales. In Canada, the Scotian shelf population lives in submarine canyons, one of which is called The Gully. In 2004, the Gully was designated a Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act. Because of this, any disturbance, damage, destruction or removal of any living marine organism or habitat within the area is prohibited. Nevertheless, contaminants and sounds can still enter the area from outside. The Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA) has considered the Scotian shelf population endangered since 2006. In 2011, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) listed the Baffin-Labrador population as “special concern,” meaning that the population may become threatened or endangered.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom