Background

By 1880, “God Save the King” and “The Maple Leaf For Ever” were popular patriotic songs and de facto national anthems in English Canada, but a national song had long been desired by French Canadians. By the mid-19th century, several compositions had been made. One of the first, “Sol canadien, terre chérie,” with words written in 1829 by Isidore Bédard and music by Theodore Molt, was short-lived. “Ô Canada! mon pays! mes amours!” was composed by Sir George-Étienne Cartier, with music by J.-B. Labelle, for the founding of the St-Jean-Baptiste Society in 1834. Other songs, such as “La Huronne” by Célestin Lavigueur and “Le Drapeau de Carillon” by Octave Crémazie and Charles W. Sabatier, enjoyed some popularity.

However, none of these songs had connected sufficiently with the general populace. In Chansons populaires du Canada (1865), Ernest Gagnon wrote of “ Vive la Canadienne” that “the melody of this song and that of Claire Fontaine take the place of a national anthem until something better comes along.” In 1878, the St-Jean-Baptiste Society of Montréal officially adopted “À la claire fontaine” as a national song.

Origin and Composition

In a letter to the National Convention of French Canadians, which was to be held 23–25 June 1880 in Québec City during the Saint-Jean-Baptiste festivities, the Reverend Napoléon Caron of the Trois-Rivières diocese suggested that a competition be held to choose a national anthem or song for the June celebration. The letter was sent on 24 January 1880, and the organizers of the festival decided there was not enough time to hold a competition, so on 15 March 1880 a music committee was appointed to produce a song. The committee consisted of 23 members, including Calixa Lavallée, Arthur Lavigne, Gustave Gagnon, Alfred Paré, Louis-Nazaire LeVasseur and Joseph Vézina. Ernest Gagnon was president and Clodomir Delisle was secretary.

Conflicting accounts were put forth over the years regarding the composition of “O Canada.” In an article in La Musique in June 1920, Blanche Gagnon claimed that her father, Ernest Gagnon, invited Lavallée to compose a national song for the Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebrations, and then asked Judge Adolphe-Basile Routhier to write the lyrics, suggesting to him the first line of the song. In December 1920, an article in La Presse titled “The Genesis of Our National Anthem ‘O Canada!’” debunked Blanche Gagnon’s story. It claimed that Routhier wrote the words first and that the lieutenant-governor of Québec, Théodore Robitaille, begged Lavallée to put them to music. This version of events, long held to be authentic, was printed in Louis LeJeune’s Dictionnaire général du Canada (1931) and Eugène Lapierre’s biography Calixa Lavallée (1936). (See also: Calixa Lavallée and the Origins of “O Canada”)

However, some key information came to light in the late 1970s. A letter from Routhier to Thomas Bedford Richardson, dated 12 February 1907, was presented to the National Library of Canada in 1975 by Richardson’s daughter, Mrs. Florence Hagerman. In this letter, written in English, Routhier declares: “M. Ernest Gagnon... was a great friend of mine and of M. Lavallée… At his suggestion, Lavallée and I agreed to compose a national song. Lavallée insisted to compose the music first and so he did — and then I made the verses, or the stanzas, with the metrical and the rhyme that were suitable to the music.”

Another letter to Richardson, dated 8 January 1907 from the lawyer and politician Armand Lavergne, contains Ernest Gagnon's own testimony, which agrees with this account. In the letter, Gagnon declares that he brought Lavallée 's music to Judge Routhier and, as an example of the rhythm he thought the lyrics should follow, suggested the first line: “O Canada! Terre de nos aïeux.”

Routhier's version of the birth of “O Canada” was expanded in comments he had provided to his grandson, Adolphe Routhier, in May 1920, shortly before his death. These notes, which were read in Parliament in June 1980 by Senator Arthur Tremblay, explain that Routhier heard Lavallée perform the “grand air” or “marche héroïque” at the latter's residence on Couillard St. and then wrote all four verses the following night.

The notes from Routhier’s grandson added that, instead of being commissioned by the music committee, as some had previously stated, Lavallée, Ernest Gagnon and Routhier took the initiative on their own, because time was short. In order not to antagonize the other members of the committee, the three persuaded Lieutenant-Governor Robitaille to commission Lavallée and Routhier “officially” to write the song.

Lavallée was apparently so excited following his composition of “O Canada” that he forgot to sign the manuscript. Arthur Lavigne signed it on Lavallée’s behalf and sent it posthaste by messenger to Lieutenant-Governor Robitaille, who asked Lavigne to become its publisher.

“O Canada” was completed in the first weeks of April 1880. In the 17 April edition that year, the Journal de Québec wrote: “At last, we have a truly French Canadian National Song!” The article added that Ernest Gagnon, president of the music committee, had approved the song by Lavallée and Routhier, and would provide “a run of 6,000 copies of the National Song, of which 5,000 will be distributed to the public.”

Original French Lyrics by Adolphe-Basile Routhier, 1880

O Canada! Terre de nos aïeux,

Ton front est ceint de fleurons glorieux!

Car ton bras sait porter l'épée,

Il sait porter la croix!

Ton histoire est une épopée

Des plus brillants exploits.

Et ta valeur, de foi trempée,

Protègera nos foyers et nos droits.

Protègera nos foyers et nos droits.

Verses additionnel:

Sous l'oeil de Dieu, près du fleuve géant,

Le Canadien grandit en espérant.

Il est d'une race fière,

Béni fut son berceau.

Le ciel a marqué sa carrière

Dans ce monde nouveau.

Toujours guidé par sa lumière,

Il gardera l'honneur de son drapeau,

Il gardera l'honneur de son drapeau.

De son patron, précurseur du vrai Dieu,

Il porte au front l'auréole de feu.

Ennemi de la tyrannie Mais plein de loyauté.

Il veut garder dans l'harmonie,

Sa fière liberté;

Et par l'effort de son génie,

Sur notre sol asseoir la vérité.

Sur notre sol asseoir la vérité.

Amour sacré du trône et de l'autel,

Remplis nos cœurs de ton souffle immortel!

Parmi les races étrangères,

Notre guide est la loi;

Sachons être un peuple de frères,

Sous le joug de la foi.

Et répétons, comme nos pères

Le cri vainqueur: Pour le Christ et le roi,

Le cri vainqueur: Pour le Christ et le roi.

First Performances and Initial Reception

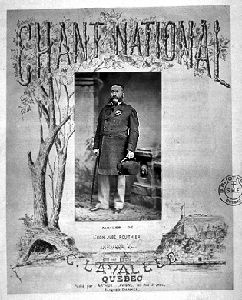

The first performance of “O Canada” took place on the evening of 24 June 1880 at a banquet at the skaters' pavilion in Québec City, attended by more than 500 distinguished guests, including the Marquess of Lorne, governor general of Canada. The song, under the title “Chant national,” was performed by three bands conducted by Joseph Vézina. It was repeated the following day at a large reception for 6,000 in the gardens of Spencer Wood. Six concert bands played the song twice, and for the first time the words were heard, sung by a full choir.

Two subsequent renditions were reported and reviewed very favourably in Le Canadien on 30 June 1880: “Yesterday morning, at the mass held in St-Roch Church, the Société Ste-Cécile graciously presented the national anthem composed by M C. Lavallée for our national holiday. This anthem has a masterful character and when sung by a great number of voices creates a most impressive effect. Our Canadian artist has been patriotically and religiously inspired by such a great festive occasion as that of 24 June.”

Concerning this performance of 27 June at St-Jean Church, Le Canada musical commented: “The magnificent national song was given most effectively after the Dona nobis. This work, in which we can recognize the composer of the Cantata to Princess Louise, is a broad, patriotic song which at the same time has a religious aspect; it seems to embody all the beauty we look for in the national song of a people, and once it spreads to our towns in Canada it undoubtedly will become the chosen song of French Canadians.”

Versions and Translations

“O Canada” is a 28-bar song written as a formal march in 4/4 time and marked “maestoso è risoluto.” The original key of G is particularly suitable for instrumental performances. A lower key — F, E or E flat — is preferable when it is sung. The original version, in G, is for four voices and piano.

The original manuscript no longer exists. The first edition has a portrait of Lieutenant-Governor Robitaille on the title page and is decorated with maple leaves. Only two copies of it are known to exist: one is held in the archives of the Séminaire de Québec, and the other at the Faculty of Music of the Université de Montréal (Villeneuve Collection). The original French publication by Lavigne was followed by several others, notably by A.J. Boucher and Edmond Hardy.

The song has appeared in many versions, arrangements and transcriptions: Jean-Baptiste Denys (Air varié sur Ô Canada for piano, Boucher 1909); Amédée Tremblay (McKechnie 1909); Edward Broome (Anglo-Canadian 1910); C.O. Sénécal (Le Passe-Temps, no. 482, 1913); Sir Ernest MacMillan (Dent 1928, Whaley Royce 1930); Healey Willan (Harris 1940); Godfrey Ridout (Thompson 1965); Kenneth Bray (Gage 1969); Rex LeLacheur (Harris 1979); and Stephen Chatman (for voice and piano, Frederick Harris 2007), among others.

Richardson Version

The popularity of “O Canada” grew rapidly in Québec, but the anthem was not heard in English Canada until 20 years later. In 1901, it was apparently sung by schoolchildren in Toronto for the visit of the Duke of Cornwall and York, the future King George V. Thomas B. Richardson translated two of the four verses from Routhier's lyrics. This version was published by Whaley, Royce & Co. in 1906, and was also sung in Massey Hall in 1907 by the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir.

O Canada! Our fathers' land of old

Thy brow is crown'd with leaves of red and gold.

Beneath the shade of the Holy Cross

Thy children own their birth

No stains thy glorious annals gloss

Since valour shield thy hearth.

Almighty God! On thee we call

Defend our rights, forfend this nation's thrall,

Defend our rights, forfend this nation's thrall.

McCulloch Version

Richardson's literal translation of the original French text was not well received, and the Canadian edition of the magazine Collier's Weekly organized a competition to find an acceptable English translation. The winner, chosen from some 350 submissions and announced 7 August 1909, was Mrs. Mercy E. Powell McCulloch.

O Canada! In praise of thee we sing;

From echoing hills our anthems proudly ring.

With fertile plains and mountains grand

With lakes and rivers clear,

Eternal beauty, thos dost stand

Throughout the changing year.

Lord God of Hosts! We now implore

Bless our dear land this day and evermore,

Bless our dear land this day and evermore.

Buchan Version

But McCulloch’s version did not catch on widely. Many other English versions were written for “O Canada,” including ones by the poet Wilfred Campbell, the critic Augustus Bridle and Ewing Buchan, a bank manager in Vancouver whose version was promoted by the Vancouver Canada Club and gained popularity in British Columbia.

O Canada, our heritage, our love

Thy worth we praise all other lands above.

From sea to see throughout their length

From Pole to borderland,

At Britain's side, whate'er betide

Unflinchingly we'll stand

With hearts we sing, ‘God save the King.’

Guide then one Empire wide, do we implore,

And prosper Canada from shore to shore.

Weir Version

However, the English version that became most widely used was that by Robert Stanley Weir, a lawyer and recorder (and later judge) with the City of Montréal. Written to mark the 300th anniversary of the founding of Québec City, it was published by Delmar Music in November 1908 with an arrangement of the music by Alfred Grant-Schafer.

Revisions were made to Weir's version in 1913, 1914 and 1916. In The Common School Book of Vocal Music, published by the Educational Book Company of Toronto in 1913, the original line "True patriot love thou dost in us command " was changed to "True patriot love in all thy sons command. " This particular change was also included in a version published by Delmar in 1914, and in all versions printed thereafter. There is no evidence as to why the change to “sons” was made, although it is worth noting that the women’s suffrage movement was at its most controversial around 1913, and by 1914 and 1916 there was an enormous surge of patriotism during the First World War, at a time when only men could serve in the armed forces.

Further minor amendments were made to Weir's version after it was widely published in 1927. Up to the middle of the 20th century, public discussion relating to the anthem, evidenced by letters to the editor in the country’s major newspapers, tended to revolve around the appropriateness of the phrase “stand on guard for thee” and the controversy associated with the tune’s perceived similarity to Mozart’s “March of the Priests.” Discussion relating to discriminatory aspects of the anthem, such as the gender-exclusive use of “sons,” began to surface in the 1950s.

Original English Lyrics by Robert Stanley Weir, 1908

O Canada! Our home and native land!

True patriot love thou dost in us command.

We see thee rising fair, dear land,

The True North, strong and free;

And stand on guard, O Canada,

We stand on guard for thee.

Refrain

O Canada! O Canada!

O Canada! We stand on guard for thee.

O Canada! We stand on guard for thee.

O Canada! Where pines and maples grow,

Great prairies spread and lordly rivers flow,

How dear to us thy broad domain,

From East to Western Sea;

Thou land of hope for all who toil!

Thou True North, strong and free!

(Refrain)

O Canada! Beneath thy shining skies

May stalwart sons and gentle maidens rise,

To keep thee steadfast through the years,

From East to Western Sea.

Our own beloved native land,

Our True North, strong and free!

(Refrain)

Ruler Supreme, Who hearest humble prayer,

Hold our dominion within Thy loving care.

Help us to find, O God, in Thee,

A lasting, rich reward,

As waiting for the Better Day

We ever stand on guard.

(Refrain)

Acquiring Official Status

By the beginning of the First World War, “O Canada” had become the de facto national anthem in French Canada, and was as popular in English Canada as “The Maple Leaf For Ever.” However, a popular consensus had yet to be reached on the English lyrics. As Liberal MP William Stevens Fielding noted in 1920: “In French Canada ‘O Canada!’ is sung everywhere. In the English Provinces the Music is heard in our parks and theatres, but seldom are English words sung to it. Whatever the reason may be, none of the English translations seem to have taken hold of the popular fancy.” But this would soon change. In 1924, the Association of Canadian Clubs declared Weir’s version their official song. In 1927, it was officially published for the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation, and began to be sung regularly in schools and at public functions.

Between 1962 and 1980, more than one dozen bills proposing that “O Canada” be adopted as the official national anthem were introduced in Parliament. In 1964, the federal government authorized a special joint committee of the Senate and the House of Commons to consider the official status of “God Save the Queen” and “O Canada.” On 31 January 1966, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson made a motion in the House of Commons stating “that the government be authorized to take such steps as may be necessary to provide that ‘O Canada’ shall be the National Anthem of Canada while ‘God Save The Queen’ shall be the Royal Anthem of Canada.”

On 15 March 1967, the special committee unanimously recommended “that the government be authorized to adopt forthwith the music for ‘O Canada’ composed by Calixa Lavallée as the music of the National Anthem of Canada with the following notation added to the sheet music: With dignity, not too slowly.” The committee also recommended further study of the lyrics. It recommended keeping the original French lyrics, but amending the existing version of Weir’s English lyrics, changing “And stand on guard, O Canada” to “From Far and wide, O Canada,” and “O Canada, glorious and free” to “God keep our land, glorious and free.”

The copyright to Weir's text had passed to Leo Feist Ltd. in 1929 and to Gordon V. Thompson Music in 1932. However, Weir’s heirs did not approve of the change to the lyrics, and though their legal standing was questionable, the government chose to settle the matter amicably. In 1970, both Thompson and Weir's descendants surrendered their rights to the Canadian government for the symbolic sum of one dollar.

On 28 February 1972, Secretary of State Gérard Pelletier introduced a bill in the House of Commons that incorporated the recommendations of the 1967 committee and proposed adopting “O Canada” as the official national anthem. However, the bill died on the order paper. (see Parliamentary Procedure.) Various subsequent bills met with the same fate.

Finally, on 18 June 1980, a bill was presented by Secretary of State Francis Fox proposing that “O Canada” be declared Canada’s official national anthem as soon as possible, in recognition of the centenary of its first performance. The National Anthem Act was passed unanimously by the House of Commons and the Senate on 27 June 1980, and received Royal assent the same day. On 1 July 1980, in a public ceremony featuring the descendants of Routhier and Weir, and the lieutenant-governor of Québec, Jean-Pierre Côté, Governor General Edward Schreyer proclaimed “O Canada” the official national anthem of Canada.

Official English Version, 1980

O Canada! Our home and native land!

True patriot love in all thy sons command.

With glowing hearts we see thee rise,

The True North strong and free!

From far and wide, O Canada,

We stand on guard for thee.

God keep our land glorious and free!

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

Amendment Proposals

Since the passage of the National Anthem Act in 1980, there have been several proposals to amend the lyrics to “O Canada.” In June 1990, Toronto City Council voted in favour of recommending to the federal government that the wording “our home and native land” be changed to “our home and cherished land” (to be more inclusive of non-native-born Canadians), and that the phrase “in all thy sons command” be changed to “in all of us command” (to bring it closer to the original “thou dost in us command” and be more gender-inclusive).

Similarly, in 2002, Senator Vivienne Poy introduced a bill proposing that “in all thy sons command” be changed to “in all of us command,” but the bill died on the order paper. In the following years, several groups criticized the reference to God in the English version and to Catholicism in the French version as being anti-secular.

On 3 March 2010, Governor General Michaëlle Jean announced a plan in her speech from the throne to have Parliament review the “original gender-neutral wording of the national anthem.” Public sentiment against changing the anthem was so strong that the Prime Minister’s Office announced two days later that the plan would be abandoned. On 30 September 2013, the issue of reverting to gender-neutral lyrics was revived by the Restore Our Anthem campaign, headed by Senator Poy, author Margaret Atwood, former Prime Minister Kim Campbell and Senator Nancy Ruth, among others.

Gender-Neutral Amendment, 2018

On 6 May 2016, Liberal MP Mauril Bélanger — who had championed the cause for years and was in the advanced stages of ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig's disease) — introduced a private member’s bill to change the line “in all thy sons command” to “in all of us command.” Bélanger made an emotional and controversial appearance in the House of Commons in June to ensure the bill moved forward. It was approved as Bill C-210 on 15 June 2016 by a vote of 225 to 74. After seven separate debates in the Senate, and following Bélanger’s death on 17 August 2016, the bill passed its clause-by-clause review in the Senate on 6 December 2016. The final vote to pass the bill into law took place in the Senate on 31 January 2018, and was boycotted by all Conservative members. The change became official when the bill was signed into law by royal assent on 7 February 2018.

Official English Version, 2018

O Canada! Our home and native land!

True patriot love in all of us command.

With glowing hearts we see thee rise,

The True North strong and free!

From far and wide, O Canada,

We stand on guard for thee.

God keep our land glorious and free!

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

Analysis and Appreciation

In his biography of Calixa Lavallée, Eugène Lapierre devotes a chapter to an aesthetic analysis of “O Canada” and refutes charges of plagiarism regarding the first bars of the anthem (which some have compared to Mozart’s “March of the Priests” from his opera The Magic Flute). Many recordings of the anthem have been made, including the first 78s in the early 1900s by Joseph Saucier, Paul Dufault, Edward Johnson, Édouard LeBel, and Percival Price.

A scrap book containing some 25 translations of “O Canada” is held at the Metropolitan Toronto Library. In 1975, the American composer Harry A. Overholtzer wrote a String Quartet in E Flat “The Canadian,” based on the theme of the anthem, recorded by the Dakota String Quartet on the Zoe label. “O Canada” is also introduced into the latter part of Walter Buczynski’s Piano Sonata No. 3 “Textures” (1991).

In 1981–82, a research project on “O Canada” was carried out by Helmut Kallmann and Patricia Wardrop at the National Library of Canada. The accumulated documents include a chronology, a selective bibliography and a classified list of some 160 publications and arrangements, 21 CBC radio documents and three films.

In 1992, at the initiative of the broadcaster Ross Carlin of Orangeville, Ontario, an O Canada Foundation was set up to create, record and distribute three contemporary musical arrangements of the anthem: one in French; one in English; and a symphonic version by Eric Robertson. More than 240 performers reflecting the musical diversity of Canada participated in the project. The foundation issued the anthem on CD, cassette and video, and presented copies in 1992 to over 14,000 schools across the country.

Legacy

The house in which Lavallée composed the anthem still stands at 22 Couillard Street in Québec City. To mark the anthem's centenary in 1980, the Canadian government issued two postage stamps on 18 June, and CBC released an album of four LPs, The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallée, devoted to works by Lavallée, Ernest Lavigne, Alexis Contant, Guillaume Couture and Joseph Vézina. The album also contains 12 choral and instrumental versions of “O Canada.”

Copyright

The National Anthem Act of 1980 declared that the melody and words of “O Canada” be left in the public domain, though it is possible to copyright specific arrangements of the melody.

A version of this entry originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom