Early Stick and Ball Games

“Hockey” is one of several “stick-and-ball games,” the origins of which may go as far back as the beginning of recorded history. There is evidence that such games may have been played in ancient Egypt and Greece and that stick-and-ball games were played by Indigenous peoples in the Americas prior to the arrival of European settlers. There is also clear evidence that stick-and-ball games were played in medieval Europe. For example, the Speculum Maius, a 13th century encyclopedia compiled by Dominican friar Vincent of Beauvais (France), includes an illustration of four men playing choule [or soule] à la crosse, a game in which players used curved sticks to move a ball toward a target.

However, hockey developed from stick-and-ball games played in the British Isles, particularly hurling (Ireland), shinty (Scotland) and bandy (England). These games shared a very similar basic structure and have been documented from the 14th century. Hurling was an ancient Irish stick-and-ball game that was originally played on the ground and resembled modern field hockey (it later evolved into the aerial game played today). In Scotland, people played a similar game called shinty (variations include shinny, schynnie and chamiare). In England, yet another similar game was called “bandy” or “bandie-ball.” The name is believed to have developed either from the verb “to bandy” (to strike back and forth) or from the bent stick used in the game. The term “bandy” was in use at least by 1610–11, when William Strachey, the first secretary of the Colony of Virginia, described a similar game played by the Powhatan Indian tribe.

Did You Know?

The bent or curved sticks used in bandy are similar to those used in early versions of cricket and golf. This has contributed to further confusion and debate among hockey historians. Many paintings by Dutch or Flemish artists in the early modern period depict the game of “kolf” (an early version of golf) played on ice with skates and using bent sticks. The most famous is The Hunters in the Snow (1565) by Pieter Bruegel. Some people have mistaken the games depicted in these paintings for early versions of ice hockey, but it is unlikely that any of them depicted a team sport.

Playing on Ice

The first reported instance of a stick-and-ball game played on ice was a game of “chamiare” (shinty) played on the ice of the Firth of Forth in Scotland in 1608, during what was known as the “Great Winter.” It is doubtful, however, that the players used skates, since iron skates were not introduced to the British Isles until around 1660. That year, the British royal family returned from exile in the Netherlands, bringing a passion for skating back with them. It quickly became a popular pastime in London, with diarist Samuel Pepys remarking in 1662 that he watched “people sliding with their skeates” on the canal in St. James’s Park, “which is a very pretty art.” Around the same time, Dutch drainage workers likely introduced metal-bladed skates to the Fens (a coastal plain in eastern England), where a vast network of canals provided much opportunity for skating.

Before long, bandy was adapted for playing with ice skates. According to historian Charles Goodman Tebbutt, people were probably playing bandy on ice since the mid-1700s in the Fens. “Concurrently with skating races, bandy matches have long been held in the Fens,” wrote Tebbutt in 1892. “It is certain that during the last [18th] century the game was played and even matches were held on Bury Fen, and the local tradition that the Bury Fenners (a team made up of players from the twin villages of Bluntisham and Earith) had not been defeated for a century may not be an idle boast. But it was not until the great frost of 1813–14 that tradition gives place to certainty.” One of Tebbutt’s sources was William Leeland, the former captain of the Bury Fenners, who confirmed that bandy had been played on ice in 1813. He also spoke to Richard Brown, who had been the umpire of a game between Willingham and Bluntisham-cum-Earith in 1827.

Bandy was also played on ice in other parts of England at the time. In February 1816, for example, the Chester Chronicle in Chester, England, reported that people were playing bandy on the frozen Dee River.

Origin of the Term “Hockey”

But what about hockey itself? Unlike bandy, hurling and shinty, the term “hockey” is relatively recent. Its oldest known use is in the 1773 book Juvenile Sports and Pastimes, written by Richard Johnson. Chapter XI of the book is titled “New Improvements on the Game of Hockey,” which suggests that the name had been in use for some years already. The chapter details the game in over 800 words, using the term “hockey” to designate not the stick, but rather the object with which it is played: a “cork-bung,” or barrel plug. This appears to contradict the most widely accepted etymology for hockey — that it came from the French word “hoquet” (shepherd’s staff) because of the shape of the stick.

Whether played on the ground or on ice, the games of hurling, shinny and bandy were usually played with a hard wooden ball, which caused frequent injuries to shins. However, around the mid-18th century, at least in England, balls were starting to be replaced by cork-bungs (barrel plugs). An engraving printed by Joseph Le Petit in London in 1797 shows such a bung being used for ice hockey. The fact that the word “hockey” appeared shortly after this switch, and that it was originally used to designate the bung, not the stick, has led hockey historians Carl Gidén, Patrick Houda and Jean-Patrice Martel to suggest that the term may have come from “hock ale.” This was a beer brewed for the festivals at Hocktide (a festival on the second Monday and Tuesday after Easter) that came in barrels with bungs that may have been particularly well suited for the game. At the time, the word “hockey” (sometimes “hocky”) was used not only to refer to the beer itself, but also as a synonym for “drunk.”

This engraving, which was published by Joseph Le Petit Jr. in 1797, is the earliest known engraving or painting depicting an ice hockey–like activity on skates.

Did this new term, “hockey,” refer to a new game? Throughout much of the 19th century, hockey and bandy were considered interchangeable terms. However, hockey appears to have become the more popular term, particularly in the London area. The last reference to a game of “bandy” in a London newspaper was in 1749, and it referred to a game played on the ground.

Origins of Hockey in England

In the 1790s and early 1800s, field hockey was played at most of the important schools in the London area, including Eton and Harrow (the first set of rules for field hockey were likely written at Harrow in 1852). Hockey thus became a common activity, on ground and occasionally on ice, and its popularity spread out of London. Several instances of ice hockey are documented in England in the 19th century. Some games are described as featuring both “skaters and sliders” (i.e., players with skates and others without), but when played by adults, it was generally played with skates. In 1853, naturalist Charles Darwin mentioned hockey in a letter to his son, William Erasmus, who was then away at school. “Have you got a pretty good pond to skate on?” he asks. “I used to be very fond of playing at Hocky on the ice in skates.”

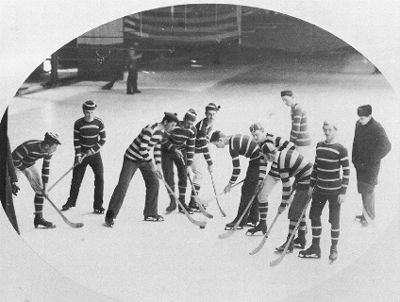

Hockey was also popular amongst the royal family. Queen Victoria’s husband, Albert, played ice hockey in the 1840s. Their son Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, participated in a particularly well-documented game played on ice with skates on 8 January 1864. The players on the prince’s team were “distinguished by a white riband on the left arm,” a precursor of team uniforms. The event was reported in several newspapers, and an illustration was published in London’s Penny Illustrated Paper, showing in detail the ribands, skates and sticks. The prince’s skating and playing skills were lauded in The Times. That evening, the Princess of Wales prematurely gave birth to Prince Albert Victor “Eddy,” who would himself prove to be an avid ice hockey player. It is possible that the royal fondness for hockey (both field and ice versions) contributed to the growing popularity of the term “hockey” over “bandy.”

Organization and Rules of Bandy/Hockey

As the 19th century progressed, and the game of hockey became more popular in England, it also became increasingly organized. England’s climate, with its relatively mild winters, would not have permitted the organization of regularly scheduled games of ice hockey/bandy, let alone a league. Yet in most winters it was possible, at least for a few days, to play hockey or bandy on ice. The activity was very popular in some areas, with newspapers reporting the game results as early as 1831 — on Saturday, 5 February of that year, the Huntingdon Bedford and Peterborough Gazette reported a bandy game between Colne and Bluntisham, which the former team won.

Then, on 3 February 1857, teams from Swavesey and Over met on Mare Fen for a game of bandy (as well as some skating races). The exact score is not known, but the local newspaper reported that Swavesey won and listed the names of all the players, eleven per side. More games were reported in local newspapers, particularly in the early 1870s, with several reports mentioning the names of the players, the score or outcome (win/draw), the goal scorers, and the duration of the game or of the intermission. This indicates a high level of formality in the organization of the game in England by at least the early 1870s.

By that time, at least two books had been published containing instructions for playing bandy or hockey — the two terms being considered interchangeable at the time — and indicating that it could be played on ice with skates. The 1849 edition of The Boy’s Own Book included a new entry for hockey, explaining briefly how the game was played (on the ground) and stating, “This is decidedly one of the most popular sports of English youth.” The article concluded by mentioning, “With a party of good skaters, this game affords fine sport, but of course can only be played on a sheet of ice of great extent.” The Boy’s Handy Book of Sports, Pastimes, Games and Amusements, published in 1863 (in London), also contained instructions on how to play the game and remarked, “Hockey is a capital winter game, and is sometimes played on the ice, and even by skaters.” (However, the authors then proceeded to advise against playing the game on ice, for safety reasons, “as falls upon the ice are uncommonly hard, especially when a few random blows from hockey-sticks increase the amenities of the fallen champion’s position.”)

Five years later, the 1868 edition of The Boy’s Own Book advertised that it had been “thoroughly revised and considerably enlarged.” The updated entry for hockey provided a list of six rules. As in the earlier edition, hockey was still enthusiastically promoted as a winter sport to be practiced with ice skates. These books clearly predate the rules published by the Montreal Gazette in 1877 and should therefore be considered the first sets of rules for ice hockey. Moreover, the Montreal rules were based on those adopted by England’s Hockey Association (HA), which was established in 1875. The HA oversaw the practice of field hockey, but its rules were also used in England for ice hockey until 1883, when the National Skating Association published its own set.

In short, by 1875, people were playing ice hockey in England and had developed rules for playing the game. This was part of a long development of the sport in the British Isles, which included games of shinty being played on ice as early as 1608.

Early Evidence of Ice Hockey in Canada

Research by hockey historians Gidén, Houda and Martel, therefore, reveals that ice hockey is not a Canadian invention, despite competing claims that various Canadian cities and towns are the true “birthplace” of the game. It is undeniable, however, that important developments in the modern game stemmed from Canada, with “Canadian rules” eventually dominating the international world of ice hockey.

There is clear evidence that the game was being played in Canada in the 19th century, even prior to the famous game played in Montreal on 3 March 1875. This is hardly surprising, given that settlers from Great Britain or Ireland would have brought with them their folk games, as would members of the British army and navy who were stationed in Canada.

The claim has been made that Windsor, Nova Scotia, was the birthplace of ice hockey. This is based largely on an eight-word passage from the book The Attaché, or, Sam Slick in England (second volume, 1844), which refers to playing “hurley on the long pond on the ice.” Although a work of fiction, some people argue that the author, Thomas Chandler Haliburton, was reminiscing about his years spent at King’s Collegiate School in Windsor, from which he graduated in 1810. The passage does not, however, provide much detail as to how the game was played or whether skates were used. Similarly, an anonymous letter to the editor, published in the Windsor Mail in 1876, describes the author’s years (1816–18) at the same school, including a reference to “hurley” as well as skating. However, the evidence is still debated, and it is unclear whether a game resembling ice hockey was played on the “long pond” at the time. Even if confirmed, however, it would still have occurred long after the 1608 game of shinty played on Scotland’s Firth of Forth and likely several decades later than the earliest bandy matches played with skates on the canals of the English Fens, not to mention also a few years later than the depiction of ice hockey found in the 1797 Le Petit engraving.

Some of the earliest evidence for ice hockey in Canada was recorded by British officers, who brought the sport with them. In 2002, for example, researchers discovered two letters written by Sir John Franklin in 1825, during one of his attempts to find the Northwest Passage. Both letters mention hockey being played on ice but do not specify that the game was played on skates (although Franklin’s diary of that expedition indicates that the crew had been equipped with them). This has led some to argue that Deline, in the Northwest Territories, was the birthplace of hockey in Canada. However, Franklin was a Royal Navy officer who would have learned about hockey (field and/or ice versions) in his home country. It is unlikely, therefore, that this was the first game of ice hockey.

There is also evidence that in 1839, games of ice hockey were played by British soldiers on Chippewa Creek in the Niagara region (although this evidence only came to light in 2008). Sir Richard George Augustus Levinge, a lieutenant of a light infantry unit stationed in Niagara, wrote in his memoirs, “Large parties contested games of hockey on the ice, some forty or fifty being ranged on each side.” He also explicitly mentions the use of skates during the games.

Hockey was also played in Kingston, Ontario, in 1843. Sir Arthur Freeling, then a first lieutenant stationed in Kingston, organized games for his men and wrote about them in his diary. Like Franklin and Levinge, Freeling was a British officer who would have learned the game in his home country. Freeling was recalled to England in 1844, and it would be a few decades before ice hockey was played again in Kingston. Despite this, Kingston was long held to be the birthplace of ice hockey, owing in large part to efforts by Captain James T. Sutherland. In 1943, Sutherland convinced the National Hockey League to adopt Kingston as the site for the Hockey Hall of Fame, based on this claim. The decision was later rescinded, and the Hall opened in Toronto.

While few reports of specific games exist, there is also no doubt that ice hockey was played on a regular basis in Halifax and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, prior to 1875. Many written sources mention the activity, although the majority refer to the game as “ricket.” Some of them are detailed enough to leave no doubt that these games were very similar to ice hockey. It is therefore clear that games resembling ice hockey were played in Canada in the 19th century, likely brought to the country by settlers or military personnel from the British Isles.

Organized Hockey in Montreal

According to the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), the first organized ice hockey game was played on 3 March 1875 in Montreal. On that date, the Montreal Gazette made the following announcement:

VICTORIA RINK—A game of Hockey will be played at the Victoria Skating Rink this evening, between two nines chosen from among the members. Good fun may be expected, as some of the players are reputed to be exceedingly expert at the game. Some fears have been expressed on the part of intending spectators that accidents were likely to occur through the ball flying about in too lively a manner, to the imminent danger of lookers on, but we understand that the game will be played with a flat circular piece of wood, thus preventing all danger of its leaving the surface of the ice. Subscribers will be admitted on presentation of their tickets.

The game, played between two teams of nine players, ended in a 2–1 win for the team captained by James George Aylwin Creighton (originally from Nova Scotia) over the team captained by Charles Edward Torrance.

James George Aylwin Creighton (12 June 1850 – 27 June 1930) was a Canadian lawyer, engineer, journalist and athlete. He is credited with organizing the first recorded indoor ice hockey match at Montreal, Quebec, Canada in 1875. He helped popularize the sport in Montreal and later in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada after he moved to Ottawa in 1882 where he served for 48 years as the Law Clerk to the Canadian Senate. Photo dated March 1902 in Ottawa, Ontario. (photo by Topley Studio, courtesy Library and Archives Canada / PA-197799)

In 2008, the IIHF officially recognized this as the first game of organized ice hockey. At the same ceremony, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, on the recommendation of the IIHF, made James George Aylwin Creighton a “person of national historic significance,” he has widely been accepted as the instigator and organizer of this game.

Was this truly the first organized ice hockey game? The game’s sticks were obtained from Halifax, as were the rules. It is likely the rules originated with members of the local British garrison, who would have been using English hockey rules. The use of a “flat circular piece of wood” to avoid injury to the spectators is often considered the “invention” of the puck (the term itself was first used in Canada in 1876). However, this ignores the use of bungs in England that began in the mid-18th century.

Newspaper reports include a list of all the players but did not provide the identity of the goal scorers, the duration of the game, or whether there was a referee or umpire, or goalies. It is also known that the players were not wearing uniforms. In contrast, there exist a few detailed reports of games of ice hockey (or bandy) from English newspapers in the early 1870s, which often included the names of goal scorers, and, in at least one case, even the times of the goals. These were clearly well-organized matches.

The Montreal game does not therefore appear to have been the first organized game of ice hockey, although of course it depends on one’s definition of “organized.” However, the sport quickly developed in Montreal following the game on 3 March 1875. Another exhibition game was played two weeks later, this time with uniforms. The identity of the teams was also more specific, with the Montreal Football Club (wearing its usual colours) facing a team from the Victoria Skating Club.

Early Canadian Innovations

In 1876, the Montreal Gazette announced that games would now be played according to rules set by England’s Hockey Association (HA). Several of the original English field hockey rules had been directly adapted from English football (soccer) rules. The offside rule, for example, was exactly the same — and not inspired by rugby, as is often claimed. Other rules also came from football, including rules against carrying the ball and how to put the ball back in play after it had gone out of bounds (the rule being different depending on whether it went off to the side or behind the goal line).

In 1877, the Gazette published the English rules, with slight modifications, including one of the two instances of the word “ground” being replaced by “ice.” The most notable changes were related to the logistical difficulties associated with playing on an enclosed rink rather than an open field. In addition, HA rules stipulated that no charging was allowed, but in the revised Montreal version, the restriction was limited to “charging from behind,” which may have implied that body checks were allowed from that point on. The Montreal version also omitted several HA rules, notably those describing the stick, how goals were scored, the size of the field and the number of players on each side.

Canadians also brought back the flat disc that had been adopted in the mid-18th century when the word "hockey" itself came into use. In Europe, cork bungs had been largely abandoned by the 1870s, and bandy/hockey was played with balls made of vulcanized rubber. (Soft rubber balls lasted longer than cork bungs and were also less damaging to shins and ankles than wood, the traditional material of bandy balls). The name “puck” was another Canadian idea — although the term itself is of Irish origin — as was the decision to produce it using hard rubber.

Canadians made other significant rule changes early on. In 1880, for example, the number of players was reduced from nine to seven. New techniques and styles of play also arose organically as the game grew and organized leagues proliferated. In the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes (1895–1911), for example, techniques such as a goaltender dropping to his knees and what may have been an early form of the slapshot were displayed prior to their use in professional hockey league play.

Early Hockey Tournaments in Montreal

The first truly competitive ice hockey games were played on 26 and 27 January 1883, when three teams competed in the first edition of the Montreal Winter Carnival hockey tournament. McGill University, the Montreal Victorias and the Quebec Hockey Club played a three-game round-robin, with McGill declared the champion. Over the following six years, four more Carnival ice hockey tournaments were held.

In 1886, the Carnival was cancelled due to a smallpox epidemic. A replacement tournament was held in Burlington, Vermont, featuring two Montreal teams and a local team, making it the first international ice hockey tournament. The same winter, four Montreal-area teams organized a season-long tournament in the city. This is considered by some to be the first hockey league, although it did not have a name and its format of direct elimination meant that there were no standings, only a champion and a finalist. Also on this occasion, the rules were revised and improved for the first time since being published. This included regulations about puck size and material, with a stipulation that they should be made of “vulcanized rubber.”

In the fall of 1886, the rules were revised once again. The most significant change affected goal size, with the dimensions set at six feet wide by four feet high (its current size). Of interest, those dimensions had already been recommended by two different authors in England in the 1860s. Still in 1886, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was formed, becoming the first, or perhaps second organized league. It lasted twelve seasons, and its 1893 champion, the Montreal Hockey Club (the hockey team associated with the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association), became the first Stanley Cup champion, having won the regular-season championship with a record of seven wins and one loss.

Influence of “Canadian Rules”

Canadian rules for ice hockey were gradually adopted overseas. In 1908, the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace (LIHG) was founded in Paris by four nations: Belgium, France, Great Britain and Switzerland. (Bohemia, a region of the present-day Czech Republic, had attended the founding meeting and joined later in the year.) The first set of rules were largely inspired by those used in Canadian hockey, and, significantly, mandated the use of a rubber puck, putting an end to the use of balls in hockey in England and the rest of Europe as national federations joined the LIHG. Bandy continued to be played in several countries (still with a ball), but its popularity declined considerably, particularly in comparison to hockey.

In 1911, the National Hockey Association (precursor to the National Hockey League) reduced the number of players to six by dropping the “rover,” with other leagues and jurisdictions following suit over approximately a decade. The offside rule was gradually made more permissive and, similarly, bodychecking went from being tolerated to being encouraged. One difference that has persisted over the years is the size of the rink. Those in North America are about 4 m narrower than — but about the same length as — those in Europe and all other countries playing under IIHF rules.

Canadian Dominance

By 1920, Canada had become the dominant power in ice hockey. That year, the first ice hockey world championship was held during the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium. It was won by the Winnipeg Falcons, representing Canada, who outscored their opponents in three games by a combined total score of 29–1. Canadian teams dominated Olympic hockey competition for over 30 years, winning six of seven tournaments between 1920 and 1952 (they settled for silver in 1936, when Britain won the gold medal with a team largely made up of players who had grown up in Canada). Canada would not win another gold medal in Olympic hockey until 2002, due in large part to the “amateur” (or “shamateur”) rules allowing countries from the Eastern bloc to send their best players while forbidding Canadian professionals to participate. However, the country has continued to be a powerhouse in international competition and has won the majority of the 12 “best on best” tournaments held between 1976 and 2014. While it may not be the “birthplace” of the sport, Canada has been the single biggest contributor to ice hockey’s evolution into the popular fast-action sport that it is today.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom