Course

The source of the Ottawa River is Lake Capimitchigama in the Laurentian Mountains, approximately 240 km north of Ottawa and 290 km northwest of Montreal. The river traces a westward arc through lakes and reservoirs including Dozois Reservoir, Grand lac Victoria, Lac Granet, Decelles Reservoir, Lac Simard and Lake Timiskaming. From Lake Timiskaming, it flows southeast, growing broad and forceful, widening into marshy lakes before constricting into turbulent rapids. From the rural areas and small towns of the Ottawa Valley, the river continues eastward through the urban centres of Ottawa and Gatineau. At Saint-André-Est, it widens to form Lac des Deux Montagnes west of Montreal, from which it enters the St. Lawrence via Rivière des Prairies, Rivière des Mille Îles and Lac Saint-Louis.

From source to mouth, the Ottawa River descends 370 m in elevation. Its own tributaries from the northern highlands are often wild and swift. These include the Rivière Dumoine (129 km), Rivière Coulonge (217 km), Rivière Gatineau (386 km), Rivière du Lièvre (330 km), Rivière de la Petite Nation (97 km) and Rouge River (185 km). From the south, the Ottawa is fed by the Petawawa River (187 km) and Madawaska River (230 km), which also flow through rugged terrain, while the Mississippi River (169 km), Rideau River (146 km) and South Nation River (161 km) drain gentler land.

Geology

The retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet some 10,000 years ago exposed land that had been depressed under the glacier’s weight (see also Glaciation). Because of its low elevation, the area now occupied by Lake Nipissing and the Mattawa River became an outlet for waters from the prehistoric upper Great Lakes. These waters flowed into the Ottawa Valley to meet the Champlain Sea (an inland extension of the Atlantic Ocean). The early Ottawa River deposited a fine clay soil in the southern valley on its journey to the sea. It formed a long, fertile path into the otherwise rocky Canadian Shield.

As the Laurentide Ice Sheet continued its northward retreat, the land gradually lifted, rebounding from its weight. A watershed formed between Lake Nipissing and the Ottawa River, separating the two systems. The Great Lakes waters formed a new channel to the sea, the St. Lawrence River. The Ottawa River eventually settled into its present course beginning in the Laurentian Mountains. From Lake Timiskaming to Montreal, the river now forms the border between Ontario and Quebec, but the division is more than political — to the south are rich farms and gentle hills; to the north the forests of the Laurentian Highlands.

Flora

The deep lakes and fast-flowing waters of the Ottawa River support few plant species. However, algae and larger aquatic plants commonly grow in its wetlands. Invasive species that grow in the Ottawa River include European frog-bit and Eurasian water‐milfoil. The dense mats of vegetation they form on or under the surface of the water stifle other aquatic plants by blocking sunlight. These plants also frustrate boaters and swimmers, in addition to blocking drainage canals and streams.

The banks of the river support many plants, including shrubs such as speckled alder, silky dogwood, sweet gale and species of the Viburnum and Potentilla genuses. Goldenrod and many fern species are also common on the Ottawa River floodplain. Spring flooding along its banks maintains alvar environments, where prairie grasses and shrubs grow on an exposed limestone surface with little soil cover. The Ottawa Valley is home to more than 85 rare flower species.

The majority of the Ottawa flows through the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence forest region. These southerly forests are a mix of coniferous and deciduous trees, including maples, white pine, red pine, eastern white cedar, tamarack, white spruce, red oak, basswood, ash, poplar, yellow birch and white birch. The endangered deciduous butternut tree also grows in this region.

The river’s northerly portions cross into the boreal forest. Conifers form most of this canopy: jack pine, black spruce, white spruce, balsam fir, trembling aspen, white birch and balsam poplar. Lichens and mosses grow on the forest floor.

The lumber boom of the 19th century cleared approximately 75 per cent of the Ottawa Valley’s forests by the 1880s. While much of this land is now occupied by homes and industry, some of these forests have regrown.

Fauna

The Ottawa River area provides habitats for many animals, despite it being one of the country’s most threatened landscapes. Dams, wastewater from municipalities and industry, and urban development all threaten the biodiversity of its ecosystems.

The river’s waters are home to many species of fish (between 85 and 96 species, depending on the source), including muskellunge, sturgeon, longnose gar, largemouth and smallmouth bass, yellow perch, walleye, northern pike and American shad (see Herring). The watershed is also home to several fish species at risk, including the river redhorse and the American eel.

DID YOU KNOW?

Longnose gar can reach 1 m in length and 10 kg in weight.

Invertebrates such as snails, crayfish and over a dozen species of freshwater mussels live in the river. The invasive zebra mussel has thrived since it first appeared in the 1980s. In addition to taking over the habitat of native mussel species, zebra mussels clog water pipes.

Common aquatic insects on the Ottawa include damselflies, dragonflies, mayflies and water striders.

The river’s sand flats, marshes and forests sustain 300 species of birds. The Ottawa is a key migratory stop for approximately half of these species. The area between Gatineau and Montebello, Quebec, is especially important for Canada geese and several species of migratory ducks. Its marshes are breeding grounds for many birds, and colonies of great blue heron exist on the river. Eleven birds of prey, such as hawks and eagles, breed in the surrounding forests.

The river’s wetlands are home to 33 species of reptiles and amphibians, including turtles, salamanders, frogs and snakes. The area is a key habitat for several at-risk species of turtle, such as the common map turtle, wood turtle, spotted turtle, spiny softshell turtle, stinkpot and Blanding’s turtles ( see also Endangered Animals).

The 53 species of mammals populating the river shores include mink, beaver, muskrat and otter, while the black bear is found near rivers and lakes throughout the Ottawa River system. The forest is home to many other mammals such as squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, raccoons, mice, bats and white-tailed deer. Along more northerly boreal sections of the river are wolves, wolverines, lynx, marten and moose.

Environmental Concerns

Pollution has been a problem since the 19th-century timber trade on the Ottawa River. The large volumes of sawdust dumped into the river from the sawmills at Chaudière Falls, directly upstream from Parliament Hill, created a very visible blight on the nation’s capital.

DID YOU KNOW?

At a public lecture in Ottawa in 1882, Irish writer Oscar Wilde called the pollution of the Ottawa River “an outrage,” stating: “No one has a right to pollute the air and water, which are the common inheritance of all.” He added: “We should leave them to our children as we have received them.”

Contamination of the river with untreated sewage from the cities of Ottawa and Gatineau has been another major problem. The sewer systems of these cities have “combined” sewers, so called because they carry sewage and storm water in one pipe. Combined sewers can overflow during heavy rains, dumping untreated waste into the river. Between 4 and 15 August 2006, an estimated 764 million litres of raw sewage spilled into the river from a City of Ottawa facility. The city was convicted under the Ontario Water Resources Act in 2008 and fined $562,500. Ottawa has since made significant progress on this issue, installing real-time monitoring and remote-control systems as part of the Ottawa River Action Plan. This achieved an 80 per cent reduction in combined sewer overflows into the Ottawa River between 2006 and 2015. In 2016, Gatineau invested in its own real-time monitoring systems to reduce overflows, which remain a challenge on both sides of the river.

Water pollution from industrial and urban sources is also a concern. Agricultural runoff containing pesticides and fertilizers can impact water quality, as can compounds that first enter residential water systems before flowing into the river (e.g., microplastics from cosmetic products).

Conservation

Because the Ottawa River supports many different species, including local human populations that rely on it for drinking water, people have made significant efforts to protect it.

In 2001, concerned citizens formed Ottawa Riverkeeper, a member organization of the international Waterkeeper Alliance. Ottawa Riverkeeper works to protect aquatic life and water quality, in addition to ensuring that the river remains accessible to the public. It also campaigns on environmental issues and responds to citizen complaints.

In 2014, the Nature Conservancy of Canada purchased a 30-hectare property near Westmeath, Ontario, that includes most of the entrances to Canada’s largest network of underwater caves. These are called the Gervais Caves, after the property’s former owners. The land includes a number of access points to the cave system and supports many species above and below water.

A 590-km section of the river along the Ontario-Quebec border was designated part of the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) in 2016. The CHRS is a federal-provincial-territorial partnership that works to protect rivers of natural, cultural and recreational importance. Following the CHRS management plan, this section of the Ottawa River is regularly monitored by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, in collaboration with other organizations.

Responding to a 2017 private members’ motion from Ottawa South MP David McGuinty, Environment and Climate Change Canada undertook a study of the Ottawa River watershed and held public consultations in 2018. One goal of the study is to create an Ottawa River Watershed Council, which would bring together different organizations and levels of government in a comprehensive plan to co-manage the river and its tributaries.

The watershed contains 26 national and provincial parks that pursue conservation efforts as part of their mandate.

Algonquin First Nations have led various initiatives to protect their traditional lands and wildlife in the region (see also Indigenous Territory). The Algonquins of Ontario have conducted research to help restore populations of the American eel to the Ottawa River. The American eel — or Kichisippi Pimisi — is listed as threatened in Canada and is sacred to the Algonquin.

In 2014, the Anishinabe Nation of the Ottawa River Watershed (ANORW) launched demonstrations and legal actions against clear-cut logging in Quebec’s La Vérendrye Wildlife Reserve. Along with the Assembly of the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador, ANORW also actively opposed the construction of a condominium on two islands at Chaudière Falls — a spiritually significant site that the Algonquin call Akikodjiwan. The development, which had the support of some members of Algonquin First Nations in Ontario, opened to its first residents in November 2018.

(See also Environmental and Conservation Movements.)

Indigenous History before 1600

The Ottawa River watershed is the traditional territory of the Algonquin people, who trace their roots back to the first occupants of the land. Indigenous people have inhabited the region since roughly 6500 BCE. Archeologists call this first era the Paleo-American period. The cultures of the peoples that followed are known broadly as the Laurentian culture of the Archaic period (c. 4500 BCE) and the Woodland culture (c. 500 BCE).

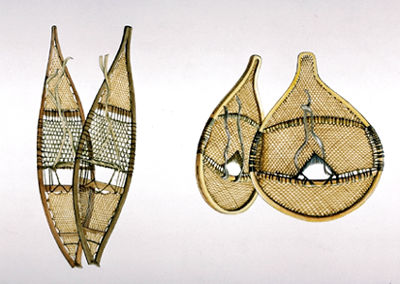

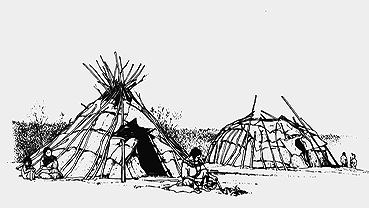

For First Nations, the Ottawa was the primary transportation route to the western interior. The Algonquin controlled the territory. They were semi-nomadic people who hunted, gathered, farmed, trapped and fished along the Ottawa River and its tributaries. They travelled by snowshoe and toboggan in the winter, and walked or paddled birchbark canoes in the summer. They lived in wigwams that they could easily take down, transport and reassemble in a new location.

From a strategic base on Allumette Island, one group, the Kichisipirini, charged other nations tolls to use the Ottawa River, as did the Nipissing in their territories. The Algonquin people called the river Kichi sipi, meaning “the Great River.”

Algonquin-French Alliance, 1600–1763

The French were the first known Europeans to have contact with the Algonquin people. This took place when the two peoples began trading around the turn of the 17th century at Tadoussac. The trade relations between the Algonquin and the French grew into an alliance. French explorers and traders began to venture further inland to Algonquin territory. Jacques Cartier probably saw the river from atop Mont Royal, but Étienne Brûlé was likely the first European to travel it during a year spent among the Algonquin in or around 1610.

In 1613, Samuel de Champlain travelled as far as Allumette Island on the Ottawa. In 1615, he travelled via the Ottawa, the Mattawa River and the French River to Georgian Bay. This became a major fur-trading route. First called the Grande Rivière des Algonquins or Grande Rivière du Nord by the French, the Ottawa River took its name from a later group of middlemen in the fur trade, the Odawa. It was a tough challenge for the voyageurs, requiring many portages, including those at Long Sault, Deschênes, Lac des Chats, Chenaux, Portage-du-Fort, Chaudière Falls, Rocher Fendu, Des Joachims, La Cave and Des Érables.

In the 1630s, having depleted the supply of beaver pelts available further south, the Dutch-allied Haudenosaunee pushed northward into Algonquin territory. By this time, many Algonquin converts to Christianity had left the Ottawa Valley for French missions in settlements on the St. Lawrence. The French attempted to defend their trade networks by providing firearms to their Algonquin allies, but they made conversion to Christianity a requirement. The Mohawk, a Haudenosaunee Confederacy nation, began to raid the Algonquin of the Ottawa Valley. During the three decades that followed, the Algonquin people were driven from their home by the Mohawk, who strove to control the fur trade.In addition, by the mid-1600s, large numbers of Algonquin people had died from epidemics of disease brought by Europeans.

In the 1660s, the French sent more troops to New France and began to force the Haudenosaunee out of the territory. This allowed the gradual return of the Algonquin to the Ottawa Valley. During these conflicts, known as the Iroquois Wars, the French government began issuing trade permits to settlers who travelled up the river as voyageurs. Unlicensed young Frenchmen known as coureurs des bois also traded furs illegally. Toward the end of the century, the French built a trading post in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue area in the upper valley; they built another in 1720.

Despite the fur trade, French settlement did not flourish in the area. L’Orignal, granted in 1674, was the first seigneury in what is now Ontario (see Seigneurial System), but the area was not colonized until the turn of the 19th century.

The Algonquin remained allies of the French until the Seven Years War (1755–63) and the British Conquest. In 1760, when Britain had won the battle for the North American colonies, the Algonquin signed a treaty of neutrality between the two European forces.

British Colonization

The British did not keep their guarantee, made in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to protect First Nations’ lands from appropriation by settlers. After the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), they responded to the influx of Loyalists in the colony by buying up land in individual sales with other nations. Some of these sales included Algonquin land, even though the Algonquin were consulted by neither party.

Hawkesbury was founded in 1798. There, Thomas Mears built the first gristmill and sawmill, and later launched the first steamer, the Union, on the Ottawa River. The first paper mill in Canada was completed in 1805 at Saint-André-Est, and Philemon Wright founded Wrightstown (later Hull) in 1800 with a group of American settlers.

Despite Britain’s broken guarantee, the Algonquin fought alongside them in the War of 1812 and helped defeat American forces at the Battle of Châteauguay. For most First Nations who allied with Britain, the alliance was strategic: they believed Britain was more likely than the United States to maintain traditional territories and trade. However, in the years that followed the war, First Nations only lost more rights and independence as settlers came to outnumber them. (See also First Nations and Métis Peoples in the War of 1812.)

In 1822, most of the remaining Algonquin land in the Ottawa Valley was sold off. Colonists continued to arrive in the years that followed, as the timber industry grew northward along the river. Despite the losses of land and life they suffered, the Algonquin remained in the region. Today, there are 10 federally recognized Algonquin communities in the Ottawa River watershed, nine of which are in Quebec. These nations have never ceded their territory by way of a treaty or similar agreement. Based on this fact, Algonquin First Nations in Ontario have launched a land claim that covers a significant portion of the Ottawa River watershed.

19th-Century Timber Trade

Log rafts descended the Ottawa even before it ceased to be the prime route of the fur trade. Philemon Wright showed that the route was feasible in 1806, and the British demand for pine grew. In 1854, the Reciprocity Treaty secured free access for Canadian lumber into the US market.

The timber trade pervaded the social life of the valley. Armies of men lived in crude shanties during winter and descended on civilization with their rafts in spring. Competition among shanties and between French and Irish led to feuds and violent clashes (see Shiners’ Wars). After the completion of the Rideau Canal (1832), Bytown (later Ottawa) grew to be a major lumber centre on the river. Though a few timber barons, such as E. B. Eddy and J. R. Booth, made fortunes, many lumbermen and Irish labourers lived in poverty and disease.

The industry swept up the river and its tributaries. By 1828, there was a lumbering operation at the future site of Pembroke. After 1850, cutting reached the Madawaska River, and by the 1870s, the western shores of Lake Timiskaming. Railways challenged the river by the 1850s, carrying lumber to Brockville and Ogdensburg, New York. By the 1870s, rail lines reached Carleton Place, Renfrew, Almonte and Pembroke. Steamers plied the river with goods and passengers, aided by a canal at Carillon, which permitted uninterrupted travel from Montreal to Ottawa.

Where land was fertile, farmers settled. Elsewhere, there remained a wasteland of stumps and debris vulnerable to fire. Part of the wilderness was saved from logging when Algonquin Provincial Park was created in 1893. In 1918, Canada’s first forestry research station was established in Petawawa to study the effects of logging, disease and fire.

Present-Day Industry and Economy

With the loss of the larger trees, most mills converted to pulp and paper. Several sawmills and pulp and paper facilities still operate in communities along the river. Much of the river’s hydroelectric power — produced by more than 40 dams and generating stations — is transmitted to other parts of Ontario and Quebec. In total, these energy projects produce at least 3,500 megawatts of electricity worth $1 million per day.

Agriculture remains an important part of the economy in the lower Ottawa Valley.

Ottawa, which was chosen as the capital of the Province of Canada in 1857, is the dominant urban centre, but its prosperity is based on the federal government, not on valley resources or its riverine connections.

The Ottawa River has been a tourist destination since the 19th century. The steamboats of that era have been replaced by sailboats, motorboats, canoes and kayaks. The rapids on the Rocher Fendu section of the river, near Pembroke, are a popular spot for white-water rafting. Other common attractions along the river include beaches, trails (for walking, hiking and cycling), ice fishing, snowmobiling, skating and cross-country skiing.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom