Paraskeva Clark (née Plistik), painter (born 28 October 1898 in St. Petersburg, Russia; died 10 August 1986 in Toronto, ON). Paraskeva Clark experienced the Russian Revolution first hand. She lived in Paris for eight years, working at an interior design shop, becoming familiar with modern art and meeting artists such as Picasso. Having married a Canadian accountant she met in Paris, Clark moved to Toronto in 1931. At first she rejected the landscapes of the Group of Seven, focusing instead on self-portraits and still lifes. She eventually began to paint landscapes in rural Ontario and Québec. Clark considered herself a socialist artist, and she believed that it is the artist’s responsibility to paint work that referred to class struggle and other social issues.

Early Life and Education in Russia

Born Paraskeva Avdeyevna Plistik in St. Petersburg, Russia, Clark (the surname of her second husband) was the daughter of a peasant factory worker who later owned a grocery store. Her mother had trained in traditional old-Russian flower-making and earned money for the family by making flowers out of cloth. Her family origins meant that she was well aware of the challenges that faced working-class families in Russia and later Canada. She had two siblings, a brother and a younger sister, and her mother died when Clark was 17.

As a young girl, Clark fell in love with the theatre and dreamed of being an actress, attending when she could afford a ticket. Due to her family’s low income, however, she was unable togo to theatre school. Instead, she enrolled in art classes at night at the Petrograd Academy of Fine Arts. In the fall of 1916, Clark started studying under the landscape painter, Savely Seidenberg. Initially she worked in charcoal from plaster heads, eventually painting and drawing from a live model. At the Academy she was introduced to work by the impressionists as well as three post-impressionists, Cézanne, Picasso, and Braque, among others.

In October 1918, following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Academy was re-named the Petrograd Free Studios, and was now under the authority of the Department of Fine Arts of the Commissariat for the People’s Education. Tuition was free for students who had previously taken classes there, or were over the age of 17, so Clark was able to begin taking classes part time. At first she studied under Vasili Shukhaev, who was relatively unknown as a painter and set designer. When Shukhaev immigrated to Paris in 1920, Clark began training with Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, one of the most influential teachers at the institution. From Petrov-Vodkin, who was known for his still lifes, Clark adopted the concept of tilting the usual verticals and horizontals, which she continued to employ in her paintings well into the 1930s and 1940s. This approach is evident, for example, in her 1947 still life Essentials of Life (private collection, Toronto), which depicts a large pear, flowers, and a candlestick (with half of a blue candle) on a table covered with a rumpled white tablecloth. In the foreground of the painting is an open book by Ezra Pound.

In March 1921, Lenin introduced the National Economic Policy, which was intended to redefine socialism in Russia. One result was that the theatres now recruited students to paint sets, and Clark was among those art students who were hired. During this time she met the son of an Italian family who worked as set designers. They married soon after, and Clark had a son named Benedict (or Ben, as he was called). The Allegri family had a home close to Paris, and Clark and her husband and young son planned to immigrate there in 1923. Clark’s husband, Oreste Allegri, drowned before they could depart for France. The Allegri family invited Clark to move in with them in France, and Clark and her young son did so in the summer of 1923.

Living and Working in Paris

For the next six years Clark raised Ben and took care of domestic duties in the Allegri household. She also attended the theatre and art exhibitions, at one point meeting Pablo Picasso, who knew the Allegris because of his connections to the theatre world (he was also married to a Russian woman at the time).

Despite not having much time to paint, Clark produced a self-portrait in 1925, now in the Art Gallery of Ontario, focusing on her broad, rosy-cheeked face, which fills the canvas. She gazes back at the viewer, pursing her lips. Her lips were one of her most distinctive characteristics, and Clark consistently represented herself over the years either unsmiling or offering only a small smile with her lips together, as in the magisterial Myself of 1933 (National Gallery of Canada), which depicts Clark in dark clothing and a hat. In this self-portrait, she portrays herself from the thighs up, her beautiful hands standing out against the dark fabric.

Needing some independence and likely time to herself, Clark began working at a shop in downtown Paris in 1929. The store sold Venetian glass and small sculptures for the home, among other things. It is at this shop that Clark first met her second husband, Philip Clark, who was visiting Europe with a musician friend, having taken a three-month leave of absence from his job in Toronto.

Paraskeva and Philip stayed in touch after Philip returned to Canada. He eventually proposed marriage, and she accepted in May 1931. They travelled to England together in order to marry on 9 June 1931. While in England, Paraskeva took the opportunity to see the exhibition Thirty Years of Pablo Picasso at London’s Lefevre Gallery. She still had the catalogue at the end of her life. Paraskeva and Philip, along with Ben, returned to Toronto together.

A Russian Artist in Toronto

Toronto, which Paraskeva Clark at some point described as a "sanctimonious icebox," was extremely conservative in the 1930s, and because of her Russian origins, Clark was regarded as exotic. She also had a strong personality that did not fit with Torontonians’ ideas about appropriate behaviour for women.

About six months after arriving in Toronto, Clark viewed an exhibition of Group of Seven landscapes. She was not impressed. More significant for Clark as an aspiring artist was the fact that the December 1931 show An Exhibition of Seascapes and Water-Fronts by Contemporary Artists and an Exhibition by the Group of Seven included 14 women artists (there were 32 artists in total). One of the artists was Emily Carr, whom Clark would soon meet. Another was Prudence Heward, whose painting of a white female nude, Girl Under a Tree (1931), which Lawren Harris argued was the best nude ever painted in Canada, was a stand-out for Clark.

A major reason that Clark was unimpressed by the Group of Seven’s landscapes was that she saw these kinds of paintings as lacking reference to the real world and social issues related to class. Her identity as a socialist — indeed she identified as a “Red Russian” communist — was also central to her identity and philosophy as an artist. There were other artists in Toronto at this time that were also conscious of class struggle, such as Bertram Brooker and Pegi Nicol, and Clark felt an affinity for artists who believed in producing socially conscious Canadian art.

Key Paintings and Exhibitions

In addition to her self-portraits, which portray Clark as a self-possessed, sometimes elegant, woman with a strong physical presence, it is her political paintings and drawings that resonate the most powerfully for viewers who regard art as inextricably linked with social issues and lived experience. Although Clark produced many still lifes, and eventually many landscapes as well as some abstract paintings (in the 1960s), paintings such as Petroushka (1937), which portrays a tightly packed crowd of people in the street, are characteristic of her best work. In the centre is a stage that rises above the crowd with a policeman puppet holding a gun and a stick, ready to beat a worker. To the left Clark has painted herself holding her infant son Clive, with her older son Ben in front of her. She has therefore inserted herself into this scene of unrest and police brutality, positioning herself as a witness, which reflected her belief that an artist must act as a witness to class struggle and other societal issues.

In March 1933, members of the Group of Seven invited a number of younger artists to a meeting at Lawren Harris’s home to discuss the state of art in Canada. The result was that the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) was formed. Their first exhibition was in the summer of 1933 in Atlantic City, and in November the 28 members had their Canadian debut at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). Clark was one of the 25 non-member artists invited to exhibit. She was elected a member in 1936. The same month that the CGP was formed, Clark showed a new painting, Portrait of Philip (1933), in the Annual Exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists at the Art Gallery of Toronto.

Clark continued to exhibit regularly. In January 1936, there was an exhibition of her paintings in the Galleries of J. Merritt Malloney in Toronto; the show received positive reviews. In 1937, Clark was offered her first solo exhibition at the new Picture Loan Society (PLS), which had opened in the fall of 1936. Significantly, Clark also made her debut as a writer that year. Elizabeth Wyn Wood, in an article in Canadian Forum, a magazine with a socialist bent, had argued that the strength of Canadian art was that it was free of day-to-day life (and by extension, politics). This idea directly contradicted Clark’s belief about art and artists’ social responsibility. She responded to Wood in an article entitled "Come Out From Behind the Pre-Cambrian Shield," which was published in New Frontier in April 1937.

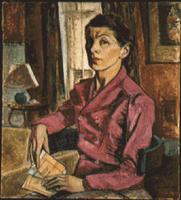

In 1942, Clark painted another self-portrait, Self Portrait with Concert Programme, which shows her seated in her living room. She is dressed in a pink suit, typical of the time, and she holds a program that she kept following a concert she had attended the previous year, Salute to Russia. Instead of painting the program, she pasted the actual program to the canvas, recalling the mixed media cubist collages produced by Picasso earlier in the century. In this work Clark’s brow is furrowed and her inclusion of the program, alluding directly to Russia, indicates her awareness of world events, namely the siege of Leningrad and the Second World War, and her related anxiety.

Near the end of the war, the National Gallery commissioned Clark to produce paintings representing the Women’s Division (WDs) of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). She produced four paintings: Bedtime Story (1945), Maintenance Jobs in the Hangar (1945, Canadian War Museum), Parachute Riggers (1946-47, Canadian War Museum), and Quaicker Girls (1946, Canadian War Museum).

A Portrait of the Artist as an Older Woman

After the Second World War ended, Clark began lecturing on Russian art. In February 1944 she spoke to two groups about Russian art and artists: the Women’s Art Society and the Art Association of Montreal at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

She also gave a lecture in 1959 on women artists at the Ridley College in St. Catharines, Ontario, singling out Emily Carr (the only Canadian artist she mentioned), as well as European artists such as Suzanne Valadon, Angelica Kauffman, and Paula Modersohn-Becker, among others.

Clark was elected a full Academician of the Royal Canadian Academy (RCA) in 1966, and in 1973, Charles Hill, then an Assistant Curator at the National Gallery of Canada, contacted her to inform her that he was planning an exhibition dedicated to Canadian art of the 1930s, and he wanted to include her in the show and interview her. The exhibition toured in 1975, and four of Clark’s works were included: Myself (1933), Wheat Field (1936), Petroushka (1937) and Trout (1940).

In 1978, Mary MacLaughlin of the Dalhousie University Art Gallery visited Clark to tell her she wanted to curate a survey exhibition of her work. The show, Paraskeva Clark: Paintings and Drawings,opened in 1982 at the Dalhousie University Art Gallery; it later travelled to Ottawa, Toronto and Victoria. Around the same time, filmmaker Gail Singer began filming a documentary about the life of Clark entitled Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom