Early Life and Education

Paul Bruchési was born to Paul-Dominique Bruchési, a merchant of Italian background, and Marie-Caroline Aubry’s on 29 October 1855. Like many young boys in Québec’s largest city, Bruchési attended an elementary school run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools. He then pursued his classical studies at the Sulpician Fathers’ Petit Séminaire de Montréal (now the Collège de Montréal) from 1867 to 1874. Thereafter, he travelled to Europe and studied philosophy, theology and canon law at several prominent institutions in Paris and Rome. On 21 December 1878, at only 23 years of age, he was ordained a priest.

Early Career

Following his ordination, Bruchési returned to Montréal and took up several different postings. He was secretary to Montréal Archbishop Édouard-Charles Fabre (1879); professor of Dogma in the Faculty of Theology at Université Laval in Québec City (1880-84); parish vicar (curate) to Saint-Joseph and Sainte-Brigide in Montréal (1885-87); chair of Christian Apologetics at Laval’s Montréal campus (1887), and director and editor of the diocesan magazine La Semaine religieuse (1887-97). After being named titular canon of the Cathedral in 1891, Bruchési took on increasingly more prominent and public roles. For instance, he was named the Sisters of St. Anne’s ecclesiastical superior (1891-1920), served as Advisory Commissioner for the Québec exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) and presided over the Montréal Catholic School Commission (1894-97).

Activities as Archbishop

Pope Leo XIII appointed Bruchési Archbishop of Montréal on 25 June 1897. From this new religious position, Bruchési oversaw a vast network of religious communities, priests, churches and parishes. As Archbishop, he supported several key initiatives, many of which relied on his close relationship with the rising number of religious congregations in the diocese. In healthcare, he assisted with the establishment of the Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur in 1898 and, in 1907, Hôpital Sainte-Justine, the province’s first French-Canadian pediatric hospital (see Justine Lacoste-Beaubien; Irma Le Vasseur). He also helped establish the Institut Bruchési in 1911, an organization aiming to thwart tuberculosis, a growing concern in the urban industrial city. Bruchési also supported the viability of social welfare and poverty-relief organizations, including the Society of St Vincent de Paul.

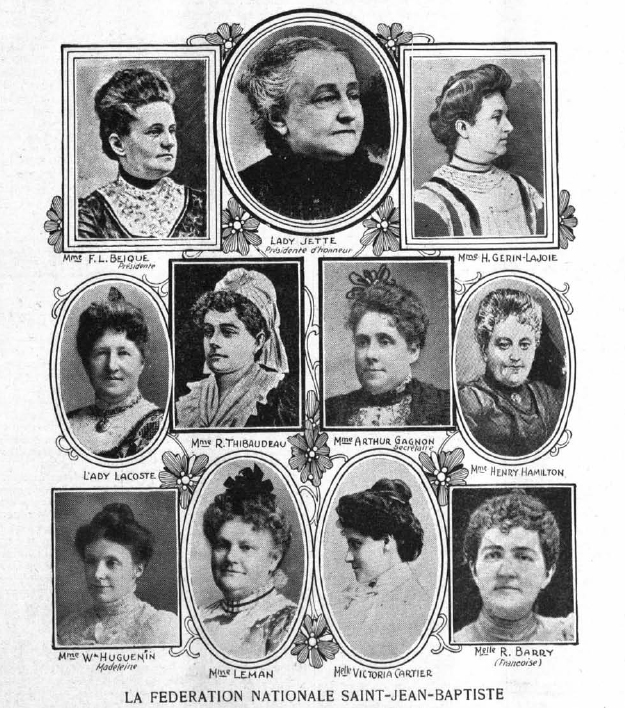

Under Bruchési’s purview, several prominent organizations and institutions were founded. In 1903, Bruchési supported the creation of the Association catholique de la jeunesse canadienne-française (ACJC), a body of fervent supporters for the protection of French-Canadian and Catholic identity and interests (see Lionel Groulx). The following year, Brother André founded St. Joseph’s Oratory. In 1907, Bruchési backed the formation of the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste, a Catholic women’s organization that played an important role in securing women’s rights in Québec. Finally, in 1919, he played a key role in securing greater autonomy for the Montréal campus of Université Laval (renamed the Université de Montréal in 1920).

The highlight of Bruchési’s episcopate came in September 1910, when the Archdiocese hosted the International Eucharistic Congress, an enormous and joyous celebration of the Catholic faith. The event brought thousands of Church dignitaries to Montréal, and the city was adorned with all manner of flags and draperies, a visible reminder to all visitors that it was a proudly Catholic metropolis. The congress included parades, reunions, lectures, speeches and a large open-air mass at Jeanne-Mance Park. The Congress culminated with a procession of about 100,000 people, and drew a crowd of around 7-800,000.

Key Issues and Controversies

Archbishop Bruchési was engaged in a wide variety of social, economic, political, linguistic and educational issues throughout his episcopate, and in the process became embroiled in controversy.

On the labour question, he supported the Catholic Church’s Social Doctrine and its emphasis on workers’ rights amidst capitalist exploitation and inequality, even participating in the inaugural meeting of the Semaines sociales du Canada. Yet he also feared that workers might turn to godless socialism and thus tried to direct them away from internationally-affiliated labour organizations and political movements and toward Church-affiliated trade unions.

Regarding morality and what were acceptable codes of conduct, Bruchési tried to impose and safeguard his understanding of what was right and decent. In 1906, for instance, he supported the federal government’s attempt to pass the Lord’s Day Act. This law, which was on the statute books until the Big M Drug Mart case of 1985, restricted business transactions and many social activities from occurring on Sundays. Moreover, through various forms of censorship, Bruchési tried to restrict access to what he considered sinful cinema, books and theatre. He thought that newspapers ought to be independently Catholic and forbade his followers from reading what he regarded as anti-clerical press, contributing to the demise of several papers. Finally, he fervently supported Ne temere, a 1907 pontifical decree that, among other rules, outlined that a marriage involving at least one Catholic was void if not conducted by a Catholic priest.

Bruchési’s reputation for cordiality amongst conflicting parties was visible amidst the tense atmosphere of the Manitoba Schools Question. In 1897, he corresponded with Pope Leo XIII, urging the Vatican to intervene on the matter. Bruchési contended that Catholic education was crucial to furthering a virtuous and civilized society, but advised a restrained tone in negotiations. His advice helped the pontiff craft a judiciously-worded encyclical, Affari vos, which contributed to a resolution of the crisis. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was enamoured by Bruchési’s tactful approach, spawning mutual admiration. More than a decade later, Bruchési took a similar approach in response to Regulation 17 and the subsequent Bilingual Schools Question (see Ontario Schools Question). His measured position stood in marked contrast with the vitriolic outrage from Québec nationalists and Franco-Ontarian leaders.

Closer to home, Bruchési was more comfortable voicing a strong opinion on educational matters. From the outset, he stridently opposed compulsory education as well as any government intervention in the Church’s dominance of Québec’s education system. In 1898 and again in 1905, he used his political influence to block proposals that would have restored a secular Ministry of Public Instruction. Bruchési supported institutions run by religious orders as well as the Church’s right to select textbooks, train teachers and design curricula. In 1908 he gave his support to the opening of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame’s Ladies’ College while thwarting women’s rights and education campaigner Éva Circé-Côté and her colleague Georgina Bélanger Gill’s secular classical college for girls (see Women and Education).

Bruchési supported Canada’s participation in the First World War. He noted that French-Canadian enlistment was one way to thank the British for protecting their right to practice their faith and their language. In doing so, he made an enemy of Henri Bourassa and many other French-Canadian nationalists. Yet, his support for military involvement was not without limits. In alignment with most Quebecers, Bruchési did not support conscription. When Robert Borden’s Union Government passed the Military Service Act in August 1917, the only concession Bruchési could secure was an exemption for members of the clergy.

Death and Legacy

In 1919, Bruchési was admitted to Hôtel-Dieu hospital with an unidentified illness. His condition deteriorated, and by 1921, he had become so debilitated that he could not carry out his duties. The auxiliary bishop, Georges Gauthier, was named apostolic administrator in 1921 and then Coadjutor Archbishop in April 1923 – meaning that he oversaw the diocese’s spiritual and administrative operations – a position he held until Bruchési’s death in 1939, at the age of 83.

Bruchési left a lasting legacy in both the city and the archdiocese of Montréal. The institutional development of hospitals, schools and social and religious organizations was unprecedented in the city. He was an able administrator, creating 63 new parishes during his episcopate, and, in 1904, organizing the detachment of the Diocese of Joliette from the Archdiocese of Montréal. While he oversaw about half a million Catholics, dozens of religious communities and hundreds of priests, he was also involved in many of the most important public issues of his era. On church matters, he sought firm adherence to the faith; on topics outside his purview, he was more amenable to fostering constructive relationships with public officials.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom