Definition: What Is PTSD?

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is regarded as a mental illness or disorder. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the most widely used manual in clinical psychiatric practice in Canada, categorizes PTSD among trauma and stressor-related disorders.

PTSD can arise in individuals exposed to direct, threatened or witnessed trauma — such as unexpected or violent death, serious injury or sexual violence (it does not usually include other life events such as divorce, death of a relative or loss of a job). It can also arise in individuals who did not experience trauma directly but learned of a close family member or friend’s traumatic experience; or who were repeatedly exposed to details of traumatic events experienced by others (vicarious trauma).

The clinical manifestations of PTSD are grouped into four categories:

- intrusion symptoms, intrusions are unintentional, spontaneous recollections or nightmares that are thematically related to the trauma. The trauma is repeatedly relived through “flashbacks” — brief, sudden and vivid replays of the traumatic event;

- avoidance, this refers to conscious efforts on the part of the traumatized individual to avoid any memories, activities or situations that remind one of the trauma;

- negative changes in cognition (thoughts and beliefs) and moods, negative moods include fear, horror, anger, guilt and shame, while distorted thoughts relate to lack of trust (“No one can be trusted”) or exaggerated fears (“The world is completely dangerous”); and,

- changes in arousal and reactivity, arousal difficulties include hypervigilance, poor concentration, irritability, impaired sleep/insomnia and a prominent startle response.

A diagnosis of PTSD is made if symptoms from all four clusters last for more than one month and interfere with work or relationships. The diagnosis of PTSD can be preceded by the diagnosis of an acute stress disorder, a condition that can develop within three days to four weeks of the traumatic event. Delayed onset PTSD refers to PTSD that develops more than six months after exposure to trauma.

Other Symptoms and Responses to Trauma

Not everyone who is exposed to a traumatic event develops PTSD. Some people do not develop any symptoms of the disorder, others develop only a few. People exposed to trauma or extreme stress can develop disorders that are not PTSD. These can include depression, anxiety, panic and various forms of dissociation. Examples of dissociation include depersonalization (a feeling of detachment from the body) and derealization (a feeling that surroundings are foggy or unclear). In addition, while PTSD is not classified as a dissociative disorder, it does include dissociative symptoms such as flashbacks and the inability to remember an important aspect of the trauma.

Associated Conditions

Although PTSD is a distinct disorder, it can be accompanied by other conditions, such as mood or anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug misuse disorders or general medical illnesses. PTSD can lead to disability, impaired functioning and interpersonal difficulties. It also poses a substantial risk for suicide. A 2013 study that looked at violent offending by UK veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars found a strong link between PTSD and hyperarousal symptoms (e.g., irritability, angry outbursts, hypervigilance) and violent offending in the deployed group.

Individuals with PTSD may be more prone to develop general medical conditions, such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Among military personnel and combat veterans who have been deployed to Afghanistan, the co-occurrence between PTSD and mild traumatic brain injury is substantial. Both PTSD and mild traumatic brain injury can present with cognitive impairments, which can overlap to a certain degree.

PTSD can be associated with various cognitive impairments, such as impairments in attention, concentration, learning and recalling new things, planning for the future, problem solving and decision making. Individuals with PTSD may also show impairments in recollecting certain episodic memories. They might be unable to consciously recall important aspects of the trauma (usually due to the psychological mechanism of dissociation, which creates a memory retrieval block).

Whether PTSD is a risk factor for developing chronic cognitive disorders of a neurodegenerative nature later in life remains to be seen. One study found that US veterans with PTSD were twice as likely to develop dementia as US veterans without PTSD. Successful treatment of PTSD is therefore imperative to decrease the risk of adverse health outcomes.

Prevalence of PTSD

It is not clear how prevalent PTSD is within the Canadian populace. The occurrence of PTSD is tracked in the Canadian military, but few studies have assessed the civilian population. In a 2008 study of 2,991 Canadians, 76.1 per cent of respondents reported exposure to at least one traumatic event. The authors of the study determined that 9.2 per cent of the respondents had experienced PTSD at some point in their lives. Men reported more frequent exposure to traumatic events, but women had higher rates of PTSD. In line with data obtained from Sweden and the United States, the type of trauma most likely to result in PTSD was assaultive violence, in particular sexual assault — which can account for the higher rates among women.

Nearly 1 in 10 Canadian military personnel who took part in the War in Afghanistan collected disability benefits for PTSD.

Risk Factors

Studies have detected certain vulnerabilities that predispose individuals to PTSD after exposure to a traumatic event. These include female gender, being younger at the time of the trauma exposure, a history of previous trauma (especially during childhood), a past psychiatric history, a family psychiatric history, lower education, and lower intelligence quotient. Social support before and after the traumatic event is a protective factor. Certain gene variants may protect an individual after exposure to traumatic events, while others may confer a vulnerability to developing PTSD. However, the genetic architecture of PTSD is not fully understood and awaits new insights from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

Dissociative symptoms (e.g., depersonalization or derealization) experienced during or just after the traumatic event predict PTSD. The nature of the trauma is also a predictive factor; acts of assaultive violence, in particular sexual assault, are especially traumatic. Post-traumatic factors that predict PTSD include insufficient or inappropriate coping strategies and trauma-related losses (e.g., financial or material loss).

Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma

The diagnosis and understanding of PTSD have importance not only for those who have been exposed to trauma, but also to their children. Intergenerational trauma occurs when a particular traumatic event reverberates through the generations of a family. However, the transmission of that trauma is not simply the reflection of a traumatic story passed down. Epigenetic research shows that its underpinnings have many layers. Epigenetics (epi meaning beyond) investigates the influence of environmental stimuli, such as stressors and life adversity, on the genome (the genetic material of an organism; see Genetics). Environmental factors, such as trauma or adversity, can lead to changes in the genome (epigenome modifications) with subsequent modifications in gene expression and the capacity to react to and adapt to stress. These epigenomic modifications can be passed on to the next generation, as data from female Holocaust survivors and their children suggest. These data are consistent with findings from animal research that show that differences in maternal care can modify an offspring’s cognitive development, as well as its ability to cope with stress later in life. (There is considerable debate about the role that maternal PTSD may play in the development and mental health of offspring.)

Michael Meaney from McGill University was one of the first researchers to identify the importance of maternal care in modifying the expression of genes that regulate behavioural and physical responses to stress, as well as the development of the brain area involved in the formation of episodic memories (memories of personal events).

The biological data pertaining to intergenerational transmission could have a profound impact on health and government policies, as well as the perception of forgiveness and responsibility. These findings, for example, provide Canadians with a new perspective on the history and legacy of residential schools and the “Sixties Scoop.”

Treatment of PTSD

PTSD is treated with an array of therapies. Cognitive behavioural therapy and prolonged exposure therapy are two “talk therapies” that are considered effective. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing is more controversial — it encourages individuals with PTSD to recall traumatic experiences while following an object that is moved back and forth across their field of vision. In this way, the individual habituates to the memory of the trauma.

Pharmacological therapies prescribe anti-depressant medication (e.g., selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors; SSRIs) in order to support behavioural therapies. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic blocker, can help reduce trauma-related nightmares and impaired sleep. However, data suggest only limited effectiveness for medication alone. A recently developed preventive approach for survivors of disasters is called psychological first aid. The main principles include fostering safety, calmness, self-efficacy, social connectedness and optimism in the aftermath of disaster.

A relatively new, but ethically controversial (see Bioethics), treatment approach is to create a substance-induced memory impairment in order to weaken traumatic memories.

Education about PTSD and its prevention, while potentially helpful, is still not widely practised. To do so will require a culture change for certain groups at risk, such as the military and law enforcement officers. In addition, the stigma of mental illnesses can hinder access to treatment and the willingness to receive treatment. (See also Contemporary Medicine.)

History of PTSD in Canada

War and Emotional Trauma

Although PTSD can arise after a variety of traumatic events, war trauma made a substantial contribution to the current conceptualization of PTSD. While the terminology for PTSD only appeared in the psychiatric classification system in 1980, knowledge of battle-related psychological problems goes back to antiquity. Mythical Greek heroes Ajax and Hercules both succumbed to their emotional wounds, not injuries of combat. In 1688, Swiss physician Johannes Hofer wrote about an unusual grouping of symptoms in Swiss mercenaries fighting in France or Italy, which he termed nostalgia. Irritable heart, also called soldier’s heart or Da Costa’s syndrome, was described in soldiers of the American Civil War by Jacob Mendes Da Costa, an American physician.The syndrome, a forerunner of PTSD, included unexplained cardiac symptoms, such as palpitations, chest pain and shortness of breath (see Heart Disease).

South African War

The term psychic trauma, which demonstrates awareness that individuals can be emotionally wounded by war, only appeared in 1878, when it was introduced by German neurologist Albert Eulenburg. However, it was not acknowledged during the South African War (1899–1902), which marked the first time Canada sent troops overseas. More than 7,000 Canadians served in the conflict, including 12 nursing sisters. While the casualty rate was low (270 killed and 252 wounded), the conflict presented many emotional hardships that went unrecognized. This was mainly due to the fact that emotionally traumatized soldiers presented physical symptoms similar to those described by Da Costa, and their origins were overlooked. One prominent critic of how the sick and wounded of the South African War were treated was Canadian physician John McCrae, who later wrote his celebrated First World War poem, “In Flanders Fields.”

First World War: Shell Shock

The prolonged duration of the First World War, and the enormous casualty rate, saw the birth of military psychiatry. At that time, the Canadian medical profession was heavily influenced and shaped by the United States and United Kingdom. Combat-related emotional trauma became known as shell shock or l’hypnose des batailles. The term shell shock captured British ambivalence about whether the symptoms found in soldiers who did not show obvious wounds were of a physical or psychological nature. Dr. Donald Campbell Meyers (1863–1927), a neurologist who opened a psychiatry ward at the Toronto General Hospital in 1906, came to view shell shock as a functional or traumatic neurosis.

During the war, Canadians established two special hospitals in England in 1915–16. Set up in existing resort-spa hotels in Granville and Buxton, shell-shocked soldiers were offered a rest cure at these hospitals. Dr. Meyers advocated a treatment for shell shock that emphasized the need for timely evacuation from combat, isolation and prompt treatment. In his opinion, “early treatment affords vastly better results than when this is delayed.” He thought that treatment should be carried out in “nervous” or neurological wards — not in wards or units where psychiatric patients were housed.

Industrial Disasters

The technological and industrial advances of the early 20th century led to other disasters and traumatic events, including railway accidents. In the process, they spawned their own, at times overlapping, terminologies. Railway spine or Erichsen's disease (after British surgeon John Erichsen) portrayed PTSD-like symptoms in travellers involved in railway accidents. Jean-Martin Charcot, the famous French neurologist, regarded it as a form of traumatic hysteria. British surgeon Herbert Page (1845–1926) viewed railway spine and traumatic hysteria as the same phenomenon. He later argued that the symptoms of shell shock had already been described in railway injuries.

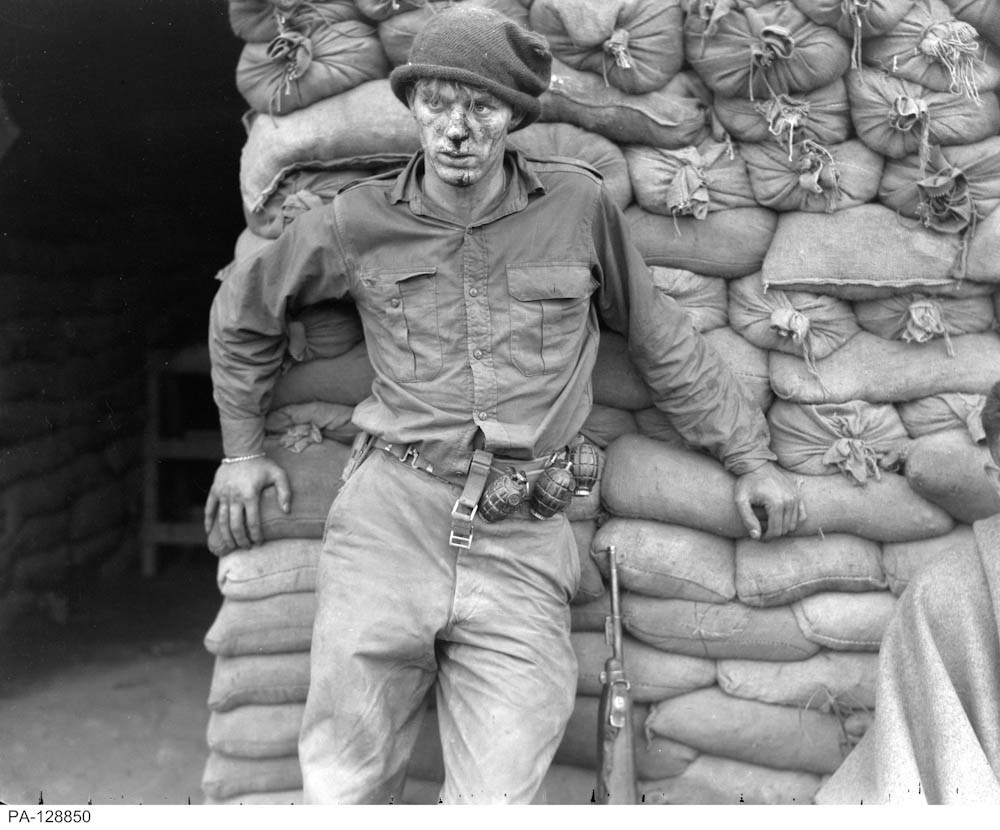

Second World War: Combat Fatigue and Battle Exhaustion

The Second World War took a heavy emotional toll on combatants. It is estimated that a quarter of all casualties were psychiatric, and that this figure was higher among soldiers engaged in prolonged combat. The terminology changed to reflect this attrition, and shell shock was replaced by combat fatigue (as named by US forces) and battle exhaustion (as termed by Commonwealth troops). Symptoms included hypervigilance, depression, loss of memory (i.e., dissociation) and physical symptoms masquerading as neurological difficulties, such as weakness, paralyses and loss of sensation.

The high psychiatric casualty rate of the Second World War arose despite preventive efforts to identify vulnerable conscripts. On 2 October 1939, the introduction of intelligence and aptitude tests during army recruiting was proposed at a conference in Ottawa arranged by the Canadian Psychological Association and defence officials. In 1941, Canada decided to employ psychologists, such as Edward Alexander Bott, to screen its armed forces. That same year, psychiatrist Brock Chisholm was appointed director of Personnel Selection for the Canadian Army (he later was promoted to director general of Medical Services).

Korean War

More than 26,000 Canadians served in the Korean War (1950–53). Though battle exhaustion and combat fatigue were understood by military psychologists, cases of psychological trauma were likely under recorded and underestimated. In 1954, a review of the psychiatric screening of recruits was published by Major F.C.R. Chalke, a medical officer in psychiatry during the war. Chalke argued that existing screening methods were not able to predict a recruit’s fitness for combat. He nevertheless stated that, “there is no evidence at hand to indicate that psychiatric screening of recruits could not be improved by well-planned research.”

War in Afghanistan

Despite research and refined screening methods, the rate of psychiatric casualties among Canadian combat and combat support personnel remains high. Many Canadian veterans of the war in Afghanistan (2001–14) suffer from PTSD. The Canadian Forces Base Gagetown Cohort Study (2011) analyzed clinical data from a group of 792 Afghanistan-deployed combat and combat support personnel at a single base (see CFB Gagetown). The study found that about 20 per cent were diagnosed with PTSD up to four years after returning from duty. Higher rates of PTSD were found among lower-ranking personnel and personnel in the combat arms trade.

The Operational Stress Injury Cumulative Incidence Study (2011) reviewed the medical records of a random sample of 2,014 personnel out of the 30,513 who were deployed in support of the Afghanistan mission between 2001 and 2008. Eight per cent were diagnosed with PTSD that was causally linked to deployment to Afghanistan. There was a brisk onset of cases in the first months and years after return from deployment. A substantial decrease in the number of new cases was noted six to seven years after return from deployment. High-threat deployment sites (such as Kandahar and to a lesser extent Kabul), low rank and Army service were identified as independent risk factors for developing PTSD. A substantial number of personnel sought mental health care in the aftermath of a difficult deployment, providing opportunity for early treatment and intervention.

As of March 2020, approximately 17 percent of Canadian military personnel who took part in the War in Afghanistan received a Veterans Affairs Canada pension or disability award for PTSD.

Emotional Trauma and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)

The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-1) was released in 1952, during the Korean War, and included the diagnostic category “Gross Stress Reaction.” It was regarded as a reaction that soldiers may face due to combat, but from which they should recover once removed from combat.

The second edition of the DSM was released in 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War. The DSM-II abandoned Gross Stress Reaction and replaced it with the diagnosis of “adjustment reaction of adult life” (under the major diagnostic category of transient situational disturbances), which was exemplified as “Fear associated with military combat and manifested by trembling, running and hiding.” This change in name and emphasis was poorly timed and also misguided given the high rates of psychiatric problems that developed in returning veterans. With time, it became clear that about one in four veterans suffered from a group of symptoms that the third edition of the DSM would finally call post-traumatic stress disorder.

The DSM-III was published in 1980. Previous DSM editions recognized acute stress disorders, but did not mention or clearly acknowledge chronic stress disorders. In doing so they overlooked the work of American doctors Roy Richard Grinker Sr. and John Patrick Spiegel, who had showed that many soldiers from the Second World War experienced greater problems when they returned home in comparison to when they were in combat zones. This seemed to suggest that a chronic stressor-related disorder might exist.

The DSM-III legitimized a post–Vietnam War syndrome that was increasingly diagnosed among US veterans in the 1970s. As such, PTSD was viewed as a chronic condition that could have a delayed onset. There was an emphasis on trauma playing a causal role in its development. The DSM-III concept of PTSD introduced three symptom categories: 1) re-experiencing the trauma (intrusive symptoms); 2) avoidance (including emotional numbness); and, 3) persistent symptoms of increased arousal that were not present before the trauma, as indicated by at least two of the following: “difficulty falling or staying asleep, irritability or outbursts of anger, difficulty concentrating, hyper vigilance, exaggerated startle response, physiological activity upon exposure to events that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.” The DSM-III was revised in 1987 (DSM-III-R), and the numbing category was amended to include avoidance and emotional disengagement.

Today, the definition of PTSD slightly differs in the two main classification systems for mental illness: the DSM-5, and International Classification of Diseases or ICD-10, (published by the World Health Organization). The DSM-5 (2013) is the most widely used manual in clinical psychiatric practice in Canada. In contrast to the previous edition, PTSD is not listed as an anxiety disorder in DSM-5, but belongs to trauma and stressor-related disorders, a view that bridges the gap between DSM and ICD.

Diagnostic criteria for PTSD in DSM-5 differ from those in DSM-IV (1994) and DSM-IV-TR (2000) in a number of ways:

- DSM-5 has elaborated on the ways in which an individual experiences a traumatic event: directly, indirectly or witnessed.

- Though it was present in DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR, subjective emotional reaction to trauma is not a diagnostic criterion in DSM-5. It was removed because not all individuals who develop PTSD experience fear, helplessness or horror in face of the traumatic event. Some individuals react with depressive feelings, some with anger, and others with a feeling of emotional detachment, blunting or numbness.

- There are now four symptom clusters in DSM-5: the avoidance/numbing cluster was attached to two separate clusters: avoidance, and persistent negative alterations in cognitions and mood.

- Flashback is explicitly described as a dissociative symptom in DSM-5.

- Dissociative symptoms in PTSD can take the form of flashbacks, amnesia, depersonalization or derealization. PTSD is not viewed as a homogenous disorder, but as a disorder that can have various clinical manifestations. Research findings from professor Ruth Lanius from Western University and others led to the inclusion of a dissociative type of PTSD in DSM-5, where the dissociative symptoms of depersonalization and derealization are dominant.

- The diagnostic criteria for PTSD in DSM-5 include separate diagnostic criteria for children ages six and younger.

DSM-5 also draws attention to culture-related diagnostic issues by highlighting that cultural idioms (“collective, shared ways of experiencing and talking about personal or social concerns“) can shape the expression of PTSD. Edward Shorter, professor of the history of medicine in the Faculty of Medicine and professor of psychiatry at University of Toronto believes that individuals possess a “symptom repertoire,” which works both consciously and unconsciously to shape the outward expression of psychological conflict. Another theory mentions that particular symptoms may appear at specific periods and partly as a result of underlying cultural and social trends. Cultural and historical contexts are moulds that shape the manifestations of PTSD, as pointed out by the work of Laurence Kirmayer, professor of psychiatry at McGill University.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom