Home of Mi’kmaq

Prince Edward Island has been part of Mi’kma’ki, home of the Mi’kmaq, for at least 10,000 years. European settlement began in the 1720s when the French called it Île Saint-Jean. France ceded the territory to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris. It became part of Nova Scotia that year.

In 1769 the island became an independent colony again, and in 1799 changed its name to Prince Edward Island.

Confederation Rejected

Like Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, P.E.I. began its path to Confederation by considering a union of the three Maritime colonies. This was initially the subject of the 1864 Charlottetown Conference. However, a contingent from the Province of Canada attended the conference, turning discussions toward a bigger union of all British North America (BNA) colonies.

Island delegates saw little benefit in joining a united BNA. The colony had a strong identity, a prosperous economy, and trade links with other Atlantic colonies and American states.

Edward Palmer, premier from 1859 to 1863 and an anti-Confederation activist, told the Charlottetown Conference that while he could see the benefits for BNA, he saw none for P.E.I. In the words of Palmer, “We would submit our rights and our prosperity, in a measure, into the hands of the general government and our voice in the united Parliament would be very insignificant.”

Still, P.E.I. agreed to consider Confederation, and sent a delegate to the 1864 Québec Conference, but was not persuaded to join the newly emerging country. Most Island newspapers backed the decision, worrying that union would increase taxation, lead to conscription for Canadian wars, and bring an end to the Island legislature. In 1866, Premier James Pope rejected the terms of the Québec Conference, which set out the constitutional details of Confederation.

While Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada entered Confederation in 1867, P.E.I. stayed out.

New Offer Turned Down

The Reciprocity Agreement with the United States expired in 1866; P.E.I. officials met with their American counterparts in 1868 to discuss new trade options, but the colony was hampered in negotiating an actual agreement without British permission.

The new Dominion of Canada, worried about the possible forging of ties between P.E.I. and the U.S., presented a deal to Charlottetown in 1869 called "Better Terms."Canada offered to assume the Island’s debts, and offered a steam ship service to connect it to the rest of the country. Canada would also pay $800,000 to buy absentee landlord holdings. Premier Robert Haythorne declined the offer in 1870.

Railway Debt

In 1871, P.E.I. began to build a railway, believing it would improve the Island’s economy and increase tourism. But the project rapidly overspent its budget and racked up debt. By 1872, the railway had put the colony on the verge of full economic collapse. In search of help, P.E.I. approached the Canadian government about joining Confederation.

Haythorne went to Ottawa for discussions in February 1873, and put the resulting Confederation deal to Island voters in a general election. He lost, but to James Pope – who also backed Confederation, but on better terms. Pope reached a new and even better deal, which the legislature approved.

Canada took on the Island's railway debt, bought land from absentee landlords, and promised to maintain a year-round communication link with the Island. P.E.I. joined Canada on 1 July, 1873. The day was celebrated in Charlottetown with bunting and streamers and a short ceremony. Pope joined the national Parliament as fisheries minister under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.

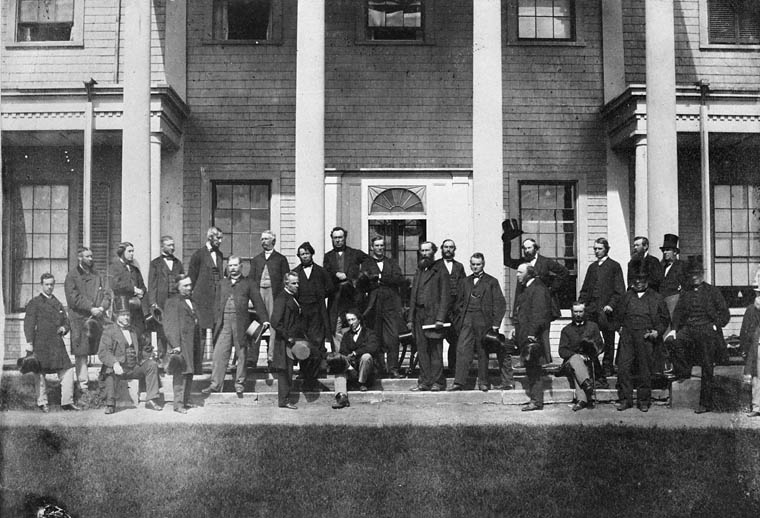

Fathers of Confederation

The “Fathers of Confederation” are the men who attended one or more of the conferences at Charlottetown, Québec and London. For P.E.I., that includes: George Coles, A.A. Macdonald, Edward Palmer, W.H. Pope, Col. John Hamilton Gray, T.H. Haviland and Edward Whelan.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom