Immigration to Canada by Southeast Asians is relatively recent; most arrived in Canada after 1974. Southeast Asia is located south of China and east of India. It consists of multiethnic nations with common histories, structures and social practices, as well as a cultural system that recognizes ethnic pluralism. Southeast Asia is comprised of 11 countries: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, East Timor and Vietnam.

In the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), more than one million Canadians indicated that they were of Southeast Asian origin. Filipino Canadians were the most numerous (662,600), followed by Vietnamese Canadians (220,425), Cambodians or Khmer (34,340), Laotians (22,090), Indonesians (18,125), Thais (15,080), Malaysians (14,165), Burmese (7,845) and Singaporeans (2,050). Southeast Asians of the Hmong people (an ethnic minority living in the mountains in the south of China, and the north of Vietnam and Laos) have also settled in Canada, as well as several hundred Chinese originally from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos who came to Canada following the “boat people” crisis.

Overview

Over centuries, Southeast Asia became a port of call for merchants from Asia and Africa, and later from Europe and the Americas. To the Europeans, Southeast Asia was known as “the East Indies.” It was a source of spices and other commercial merchandise, which were becoming more and more important in their daily life. These commercial interests led to the colonization of Southeast Asia during the 19th century by France (Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam), the United Kingdom (Burma, Malaysia and Singapore), Spain (the Philippines), Portugal (Timor), the Netherlands (Indonesia) and the United States (the Philippines beginning in 1898).

Occupied by the Japanese army during the Second World War, the colonies of Southeast Asia gained their independence in the postwar years. The Philippines was the first to gain independence in 1946, followed by Burma in 1948. Indonesia’s independence was proclaimed in 1945, but it was followed by a social revolution and an armed conflict. It was only in December 1949, after four years of clashes, that the Netherlands recognized Indonesia as an independent state.

The French Indochinese countries (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) gained their independence in 1954, at the end of an eight-year war that caused more than 500,000 casualties. The result was the division of Vietnam into two rival states and a new armed conflict, the Vietnam War, which had repercussions throughout the region.

Malaysia gained its independence in 1957, and in 1963 the former British territories of Sabah and Sarawak, located on the island of Borneo, entered the Federation of Malaysia. Singapore, which was a member of the federation starting in 1962, left in 1965 to become an independent state. In 2002, East Timor was the last Southeast Asian country to gain its independence. Thailand has been a constitutional monarchy since 1932, but it is regularly shaken by military coups. Brunei is an absolute monarchy.

It was only after the Second World War that the expression “Southeast Asia” came into use. The terms “Indochina” or “Indochinese peninsula” had long been used to refer to mainland Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore), while “Insulindia” referred to the Southeast Asian island countries and territories (Brunei, Indonesia, the Philippines, East Timor and the Malaysian islands). Today, these countries (with the exception of East Timor) are all members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Founded in 1967, this organization’s goal is to foster cooperation and mutual assistance among its members in the areas of politics, economics and culture.

Different ethnic groups from Southeast Asia settled in Canada.

Canadian Encyclopedia articles on Canadians originally from Southeast Asia:

Cambodian or Khmer Canadians

Indonesian Canadians

Laotian Canadians

Malaysian Canadians

Filipino Canadians

Vietnamese Canadians

Thai Canadians

Migration History

During the 1960s, political instability pushed many Indonesians to immigrate to Canada. The majority of them were ethnically Chinese (90 per cent), but because of linguistic differences, they were not close to the Chinese Canadian community. Canada also welcomed many hundreds of students from Southeast Asia as part of the Colombo Plan. Since the 1950s, more than 80,000 Malaysian students have come to Canada to study, and several hundred have decided to settle there. From 1973 to 1984, 6,872 Malaysians immigrated to Canada.

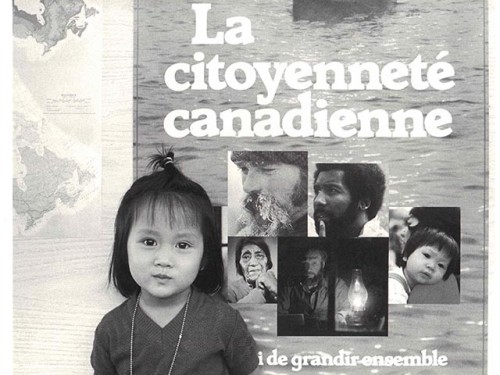

The Indochinese (Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians) came to Canada in five waves. Some arrived as students during the 1950s and 1960s and decided to stay. As a result, by 1970, about 1,200 Vietnamese and several hundred Laotians and Cambodians had settled in Canada, principally in Quebec. The retreat of American troops from Vietnam and the fall of the South Vietnamese Thiêu regime on 30 April 1975 led to a massive migration of Vietnamese. Close to 6,500 of them were admitted to Canada as political refugees.

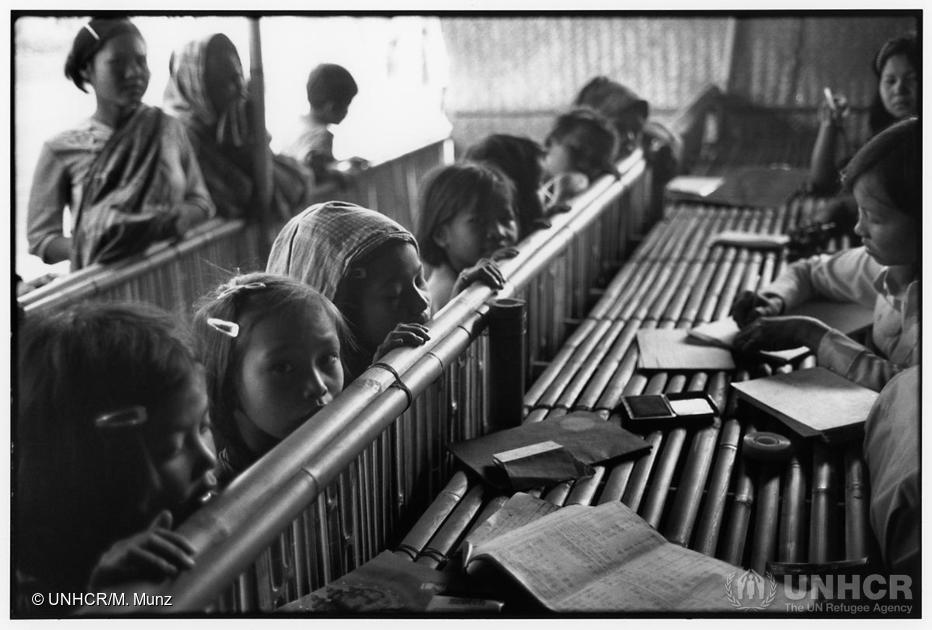

By the end of 1975, all of the former Indochinese territories were governed by totalitarian and communist regimes. On 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge seized the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, along with other cities, ensuring their complete domination of Cambodia. In Laos, the communist revolutionaries of the Pathet Lao, which had taken power at the beginning of the year, abolished the monarchy on 2 December 1975 and proclaimed the country the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. At the end of 1978, an armed conflict broke out between Vietnam and Cambodia, adding to their peoples’ distress.

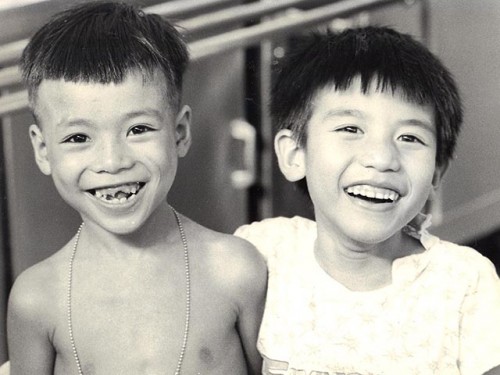

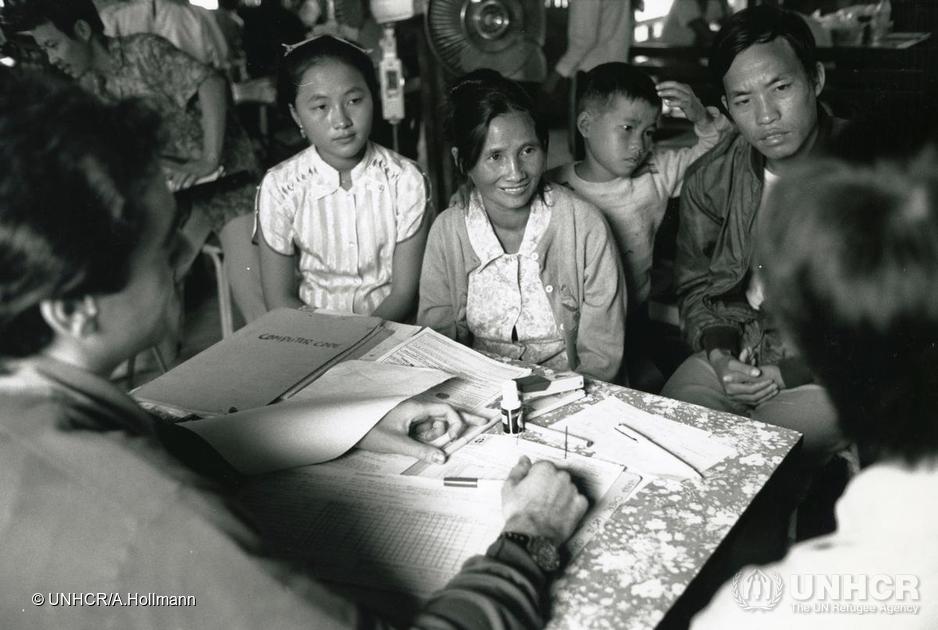

The political context, the rapid deterioration in living conditions, and human rights violations in these countries would unleash a migration that was unprecedented in that part of the world. Following the invasion by the Vietnamese, several thousand people set out from Cambodia to Thailand on foot. Starting in late 1978, the exodus of Vietnamese, as well as Chinese from Vietnam and Laos, grew to dramatic proportions, with many thousands fleeing on makeshift boats via the South China Sea and the Mekong River. The “boat people” who survived this risky crossing were welcomed in camps established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Hong Kong. As the situation for these immigrants continued to deteriorate, Canada admitted 59,970 refugees and immigrants from Southeast Asia in 1979 and 1980.

From 1981 to 1986, many Indochinese continued to arrive as political refugees or designated-class immigrants: 24,000 from Vietnam, 3,400 from Laos and 8,900 from Cambodia. At the same time, 16,500 people arrived from Vietnam through the normal immigration process (1984–1986). By the end of 1986, Canada was home to 130,000 Indochinese, 95 per cent of whom were refugees or recent immigrants. Efforts undertaken from 1987 to 1996 by Southeast Asian Canadians to be reunited with their families contributed to a 50 per cent increase in the immigrant population in Canada. The Indochinese then emigrated in large numbers from Canada to the United States and, since 1990, there has been a modest movement to return to Vietnam. Since 1997, Thailand has experienced a financial crisis, which has pushed many Thais to look for professional and educational opportunities abroad, including in Canada.

Since the 1970s, but especially since 1986, Asia in general has produced more than half of newcomers to Canada. In 2006, immigration from Asia outstripped immigration from Europe for the first time in the history of Canada, and this trend continues. According to the 2011 NHS statistics, Filipinos formed the largest number of new immigrants to Canada from 2006 to 2011 (152,300 people and 13.1 per cent of all new immigrants).

Settlement and Socio-Economic Data

In 2011, 91 per cent of the population born abroad and most of the 1,162,900 immigrants who arrived in Canada in the five preceding years lived in metropolitan regions and urban communities (compared to 63.3 per cent of the Canadian-born population). Most working-class Southeast Asians live in urban areas that include commercial and institutional sectors with stores, restaurants and religious institutions.

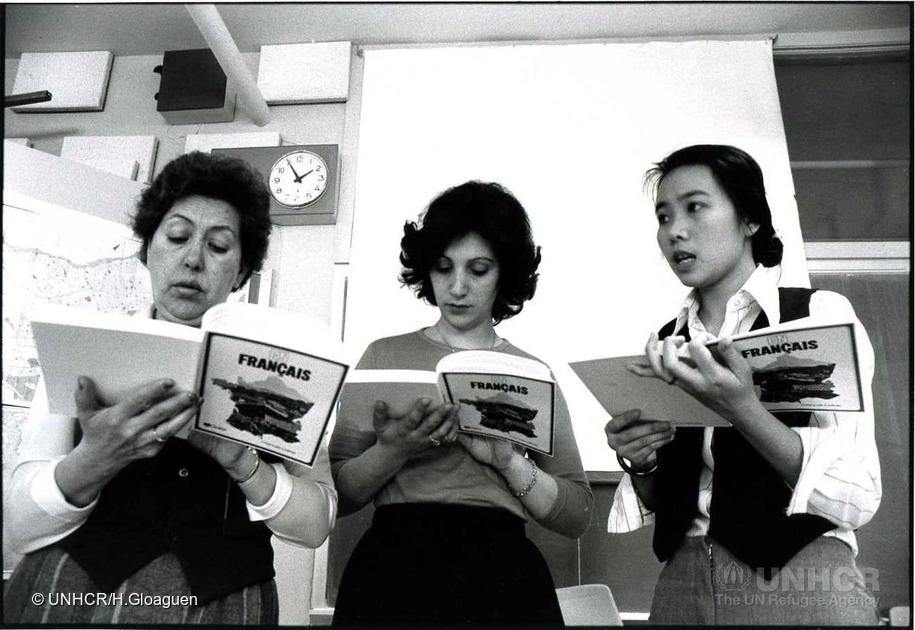

For Southeast Asians, adapting to Canadian society means integrating into life in Canada while maintaining their affiliation to and identification with their ethnic groups. Some Southeast Asians face prejudice and discrimination when they try to compete in the labour market. Perceived discrimination, as well as unemployment and linguistic barriers, continue to be a burden for Southeast Asians who have settled in Canada. These stressors related to resettlement evoke a strong feeling of ethnic identity, which may slow the immigrants’ cultural adaptation and negatively impact their general well-being.

Cultural, Religious and Community Life

Almost all adult Southeast Asian immigrants use their mother tongue at home, in the community and often at work. Cantonese serves as the language of Chinese business in Cambodia and Laos, and many Chinese coming from these countries speak it as well. Chinese immigrants from Vietnam and other Chinese Canadians with Cantonese origins have many common cultural and linguistic traits. Nonetheless, Vietnamese of Chinese origin identify strongly with their Vietnamese heritage and have formed cultural associations in many cities.

Most Vietnamese practice Mahayana Buddhism, and they have formed Buddhist associations throughout Canada. Mahayana Buddhists, like Confucians, Taoists and ancestor worshippers, perform most of their religious rites at home. For religious activities associated with the life cycle, they make use of Chinese-Canadian institutions. Vietnamese Catholics generally join existing Catholic parishes, but sometimes they have their own religious organizations or parishes, like their counterparts in other Christian denominations. The Vietnamese are working to create community organizations throughout Canada, which become major centres for the cultural events and recreational activities that contribute to the maintenance of socio-cultural traditions. At the national level, the Vietnamese Canadian Federation, an umbrella organization for several local associations, works hard to preserve Vietnamese culture and to facilitate integration into Canadian life.

Laotian and Cambodian groups practice Theravada Buddhism, which distinguishes them markedly from Vietnamese Buddhists in matters of religion. Laotian and Cambodian monks, as well as religious organizations in many areas of the country, carry out a growing number of religious ceremonies essential to personal and collective identities within these populations. However, Laotian and Cambodian cultural associations have not yet experienced the growth seen by similar Vietnamese organizations. Most Malaysians and Indonesians who have immigrated to Canada are Muslim; in fact, Malaysia and Indonesia are home to the majority of Southeast Asian Muslims, although followers of Islam are also found in the Philippines and Thailand.

The Malaysian Association of Canada, located in Toronto, organizes many activities for Southeast Asians living in that city. McGill University, Queen’s University and the University of Alberta all have Malaysian student associations, and several Canadian universities are home to Southeast Asian student associations representing a number of the ASEAN member countries.

Canada and Southeast Asian Countries

Canada engages in bilateral relationships with most of the Southeast Asian countries and has embassies in the majority of those countries. Canada also collaborates with the 10 member states of ASEAN as a dialogue partner. The aims of this collaboration are to reduce poverty, promote trade, protect human rights, and support democracy and the rule of law. Canada has recently adopted an ASEAN-Canada Action Plan (2016–2020) which sets out areas of cooperation for the coming years: politics and security, economic and socio-cultural cooperation, connectivity, and development cooperation, to name just a few. Canada currently gives $14 million to member states for security purposes. In 2013–2014, Canada gave $320 million in development aid and, in 2015, Canada-ASEAN trade rose to $21.4 billion.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom