The time between the end of the Second World War and the signing of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 is often referred to as the Rights Revolution in Canada. During this period, awareness of and support for human rights increased. At the grassroots level, women, queer communities, Indigenous peoples, and disability activists pushed for greater inclusion and made significant rights gains. At the same time, both federal and provincial governments passed laws that prohibited discrimination and protected human rights for more people across Canada.

1945 to 1960

Before the Second World War, different marginalized groups in Canada pressed for such things as voting rights and the end of racial discrimination. (See Early Women’s Movements in Canada; Black Voting Rights in Canada; Indigenous Suffrage.) Although progress was uneven, human rights awareness and activism gradually increased in Canada. At the end of the Second World War, there was a greater push internationally to legislate human rights due to global efforts for peace and co-operation.

Politicians across Canada set to work. Ontario began this movement by passing The Racial Discrimination Act in 1944. It banned any publication or other display of discrimination against a person or peoples’ race or belief. In 1947, the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights Act became the first bill of rights in Canada. It covered freedoms of conscience, expression, association, and freedom from arbitrary imprisonment. It also preserved people’s rights to elections, employment, property, and education. Like Ontario’s act, the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights also prohibited the publication or display of discriminatory restrictions based on someone’s race or belief. It went further, though, by including grounds of religion, colour, ethnicity, and nationality. Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, many provincial and territorial legislatures followed suit with their own human rights codes.

These national developments related to Canada’s influence on the world stage at the time. After the horrors of the Second World War, many in the international community shifted their focus to the prevention of violence and the protection of people. Canadian law professor John Humphrey became director of the United Nations’ (UN) Division on Human Rights in 1946. He worked closely with Eleanor Roosevelt, the United States’ representative to the UN Commission on Human Rights. Humphrey wrote the first draft of an international bill of rights that would eventually become the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Canada nearly abstained from the vote. But on 10 December 1948, it joined other UN members in adopting the UDHR. (See John Humphrey, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.)

1960s and 1970s

In the 1960s and 1970s, people organized themselves into shared interest and/or identity groups. (See also Pressure Group.) They sought to strengthen their political influence and improve their lives by using the language of rights. Women’s rights continued to gain support with the rise of second-wave feminism. Women were at the forefront of nuclear disarmament and anti-Vietnam War protests. (See also Peace Movement.) They also rallied around issues of increased representation, employment and educational opportunities, as well as bodily autonomy. (See Abortion in Canada.)

During this era, limited rights gains were also made by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities. (See also Queer Culture; Pride in Canada.) Their efforts brought about safety and acceptance for the queer community at large. This included the decriminalization of sexual relations between men over the age of 21 in 1969. In 1977, Quebec became the first province to ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Disability rights activists also sought more civil rights during this period. One of the key issues was opposition to their own institutionalization. The disability rights movement in Canada was also strengthened by the experience of veterans returning from war. Injured veterans received superior care and acceptance compared to their disabled civilian counterparts. This led disability activists and their supporters in the veterans’ movement to push for greater rights for all Canadians with disabilities.

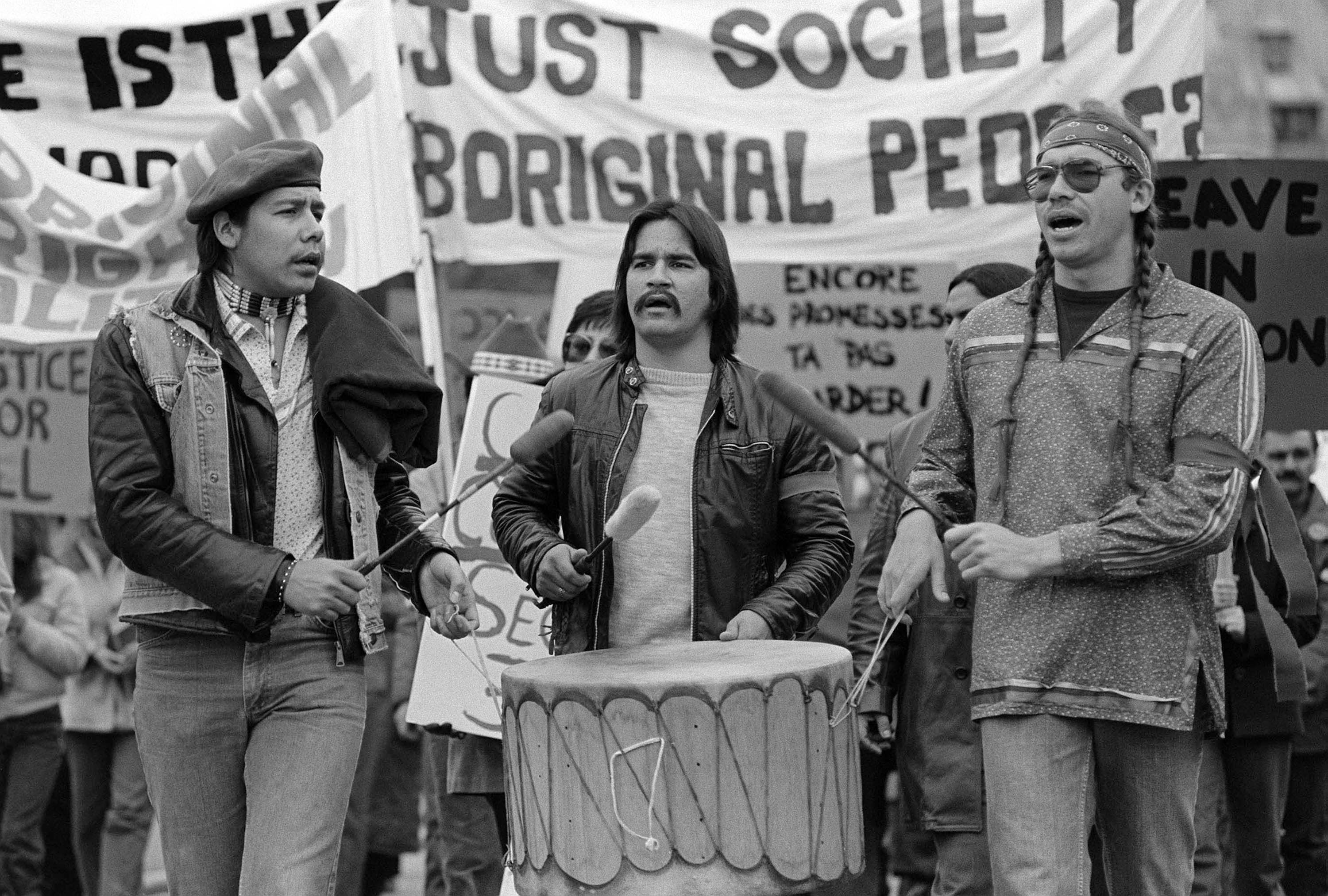

Indigenous peoples also used human rights language to push for rights to resources, land, and self-government. Indigenous peoples made more political gains as provincial and federal governments became more receptive to claims made through the language of human rights. (See Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada; The White Paper, 1969.)

Governments responded to this grassroots activism by writing laws that protected human rights. The first law to protect human rights at the federal level was introduced by Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in 1960. The Canadian Bill of Rights was groundbreaking, but limited; it only applied to federal laws and government actions.

But provincial laws were becoming more effective. In 1962, Ontario’s anti-discrimination laws were consolidated under the Ontario Human Rights Code. This provincial act also created the Ontario Human Rights Commission. Quebec’s Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms faced delays while the government sought separate language rights legislation. It was adopted in 1975.

At the federal level, the Canadian Human Rights Act passed in 1977. (See also Canadian Human Rights Commission.) By this time, most provinces and territories were governed by their own human rights laws; as a result, the federal act only applied to employees or beneficiaries of the federal government, First Nations, and federally regulated private companies. With increased legal protections at both levels of government, human rights advocacy across the country made powerful gains.

1980s and Beyond: Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

In 1982, Canada’s Constitution was patriated. This meant that the Canadian Parliament could change the Constitution without approval from the British Parliament. The Constitution Act, 1982 also entrenched the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It became a permanent fixture in the highest law of the land. As a result, the human rights outlined in the Charter superseded the Canadian Bill of Rights.

The Charter is a broader human rights law than the Bill of Rights and has more power; this is because it covers both provincial and federal laws and actions. It has influenced how courts make their decisions in rights cases. It has also encouraged those who write laws and policies at all levels to abide by Charter rights in the first place. The Charter includes freedom of expression and religion; the right to a democratic government; the right to live and seek work anywhere in Canada; the legal rights of people accused of crimes; the right to equality; the right to use Canada’s official languages; and the right of French or English minorities to an education in their language.

Since 1982, individuals and groups have used the court system to further clarify the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter. Significant progress has been made; but it continues to be slower for some groups than for others. Indigenous peoples, for example, continue to seek equal rights including access to adequate housing, accessible education, and safe drinking water. (See Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

See also Rights Revolution (Plain Language Summary); Liberalism; Social Justice; Ethics, Social and Political Philosophy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom