On 26 August, Amundsen heard the lookout cry “Sail. Sail ahead!” Amundsen knew instantly what it meant. They were in open water and had spotted a whaling ship from the Pacific. In his diary he wrote: “The North-West Passage was done. My boyhood dream — at that moment it was accomplished. A strange feeling welled up in my throat; I was somewhat overstrained and worn — it was a weakness in me— but I felt tears in my eyes.”

Amundsen seemed destined to be one of history’s greatest explorers, worthy of his Viking ancestors. Born in southeast Norway, he grew up devouring stories of polar exploration, particularly the ill-fated journey of the British explorer, Sir John Franklin (see Franklin Search). He gnawed leather and bones, strengthened his physique, and endured hardships to prepare himself for the hazardous adventures ahead.

After proving his leadership and courage on a Belgian-financed Antarctic expedition in 1894, Amundsen obtained his captain’s ticket and set about planning his own Arctic expedition: to search for the Northwest Passage.

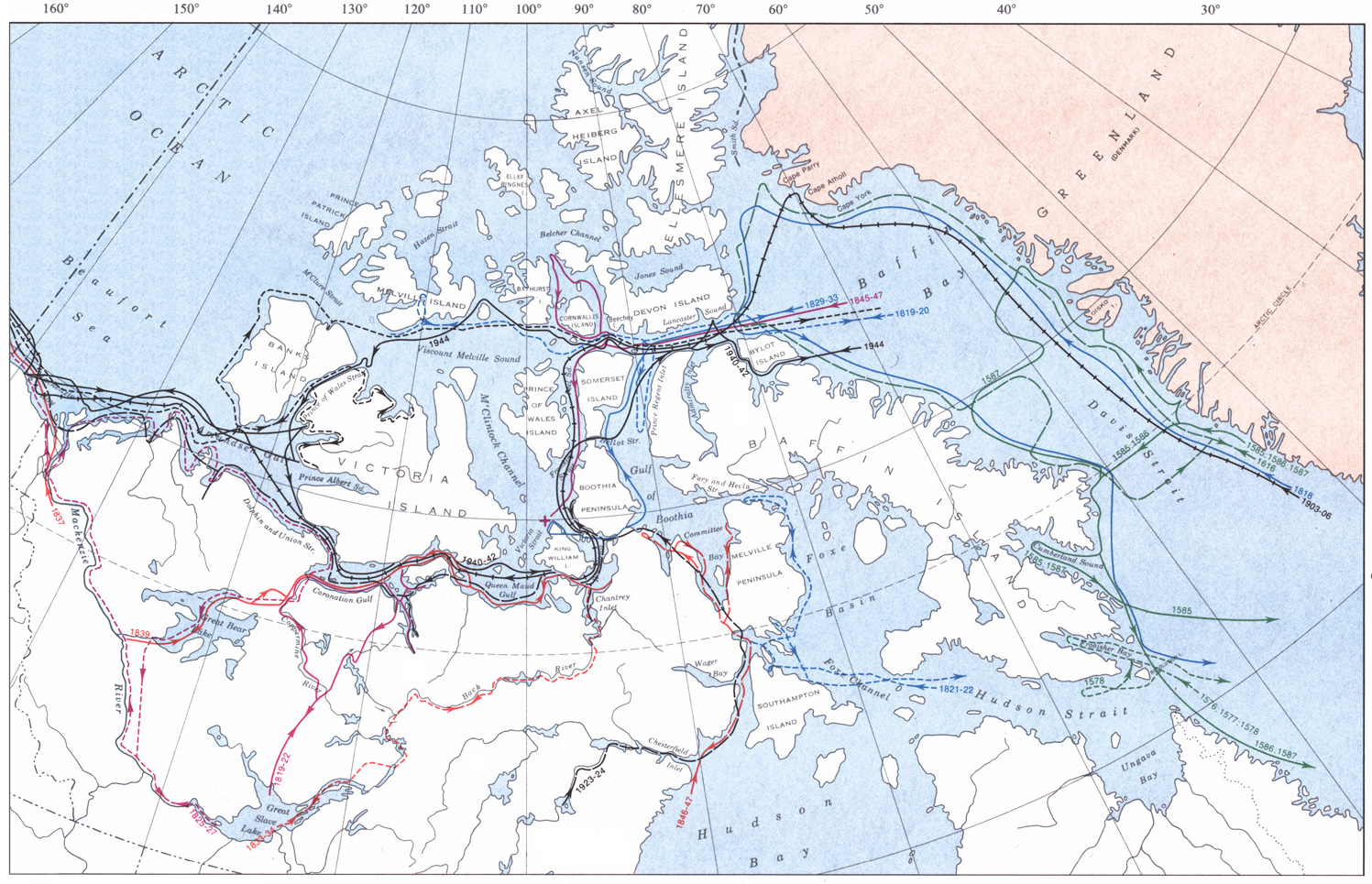

When Amundsen and his little ship the Gjøa set sail on 16 June 1903 towards the North Sea, he knew full well that he was embarking on an adventure that had ended in disappointment and disaster for so many before him.

At Godhaven, west of Greenland, Amundsen took on supplies and purchased a score of Husky dogs (see Dogsledding). The now heavily laden ship struggled in the frightful squalls of Melville Bay, notoriously one of the worst bodies of water in the world. Amundsen told his frightened crew to “Rely on me. Best of all, rely on the Gjøa. I understand her and she understands me.” At last, the Gjøa rounded Cape York and landed on dreary and lonely Beechey Island, deep in Lancaster Sound.

From Beechey Island the Gjøa slipped into the mists of Peel Sound, which was the farthest point yet reached by any explorer. After an onboard fire and two groundings, it reached the south coast of King William Island and found a protected harbour Amundsen called Gjøahavn (meaning Gjøa Harbour) for his ship (see Gjoa Haven). While Amundsen set up his instruments in several locations and was able to collect enough data to locate the North Magnetic Pole (see Magnetic Poles), he failed in several attempts to reach the North Pole overland.

Amundsen went to live among the Inuit, who taught him how to survive in the world’s most extreme region. Amundsen was astonished at their happiness and when he left them he wrote “I don’t think that we will ever meet better people in our lifetime.”

The arduous journey through the Northwest Passage took its toll on Amundsen. He was 33 but he looked 63. His face kept the same lean, gaunt look for the rest of his life. On 2 September the Gjøa slowed its progress off King Point on the north coast of Canada. One whaling captain, anxious to return overland to San Francisco, persuaded the penniless Amundsen to take him. With two Inuit guides the party crossed a ridge of mountains and on 5 December 1905 reached Fort Egbert. There, by telegraph, Amundsen informed the world of his triumph.

Amundsen could only add to his fame with his astonishing voyage to the South Pole. By travelling light, with dog sleds — in contrast with the doomed expedition of Robert Falcon Scott — Amundsen made relatively easy progress across the vast plateau to the South Pole itself.

When in May 1928, Amundsen heard that the Italian explorer Umberto Nobile’s airship had crashed in the Arctic, without hesitation he volunteered to take part in a rescue attempt. In June, his aircraft crashed three hours after it took off from the town of Tromso. Fridtjof Nansen wrote perhaps the best epitaph for history’s greatest polar explorer: “Amundsen... had set his course, as he had determined, and without looking back... What does it not convey of a sage, well laid plan, and splendid execution of determined courage, endurance and manly power?”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom