Ross Munro, OBE, OC, journalist (born 6 September 1913 in Ottawa, ON; died 21 June 1990 in Toronto, ON). Munro was one of Canada’s foremost Second World War correspondents. He also reported on the Nuremburg trials and the Korean War. Munro later became editor of the Vancouver Province and publisher of the Edmonton Journal, Montreal Gazette, Winnipeg Tribune and the Canadian Magazine. He became an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1946 and Officer of the Order of Canada in 1975.

Family and Education

Munro was born in Ottawa, the son of a parliamentary press gallery reporter, and a grandson of the founder of the Port Elgin Times. Munro graduated from the University of Toronto in 1936. Following his studies, he followed in his father’s footsteps and began work as a reporter with the Canadian Press (CP) in Ottawa. Munro served in various CP bureaus across Canada, as well as in New York and Washington, before going overseas as a war correspondent in 1940.

War Correspondent

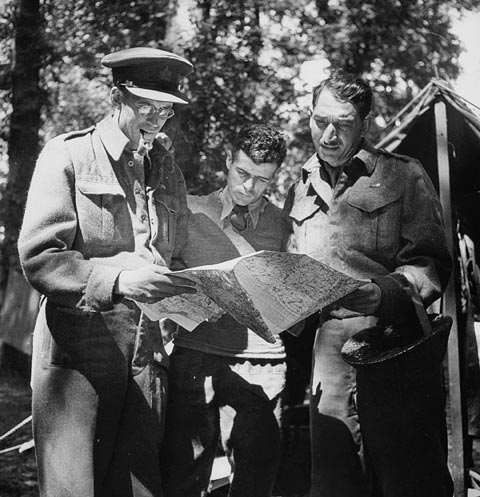

The 26-year-old reporter arrived in London in the summer of 1940 during the Battle of Britain and would go on to be one of CP’s most popular war correspondents, seeing “more action than most Canadian soldiers.” Ross Munro reported on the North African campaign and the Italian campaign, as well as four amphibious landings: Spitsbergen, Norway; the Dieppe Raid; the Allied landings in Sicily, and the D-Day landings at Normandy and the subsequent campaign in Northwestern Europe. He was also present at the Nazi surrender in the Netherlands on 7 May 1945 and the declaration of Victory in Europe the following day.

Reporting from London

Upon his arrival in London, Ross Munro recalled, “I was committed to the war completely and utterly, right from the start. Maybe it was jingoism, chauvinism and stupidity, but we felt that the Germans were going to wreck this world of ours and we would have to stop them.”

In 1940, the Canadian Press began delivering broadcast copy called The Canadian Press Newsletter to CBC Radio “for 15-minute broadcasts to the Canadian forces overseas.” By May 1942, the newsletter became a four-page tabloid, The Canadian Press News, with 30,000 copies published weekly for distribution to servicemen. Munro’s reports appeared frequently in the tabloid.

Operation GAUNTLET

By mid-August 1941, Munro was assigned to report on Operation GAUNTLET, an Allied Combined Operation to the German-dominated island of Spitsbergen in the Svalbard Archipelago, 1,050 km from the North Pole. Spitsbergen was on the Arctic convoy route to Archangel [Arkhangelsk] and Murmansk, Russia.

Two months earlier, on 22 June, the Germans had launched their attack on Russia. The Allied plan was to aid Russia by depriving the Germans of the valuable coal mines at Spitsbergen. Canadian Brigadier A. E. Potts commanded Force 111, which consisted of 46 officers and 599 other ranks (of whom 29 officers and 498 other ranks were Canadian). GAUNTLET was a success, as the Allied troops destroyed coal mines and shipping infrastructure. According to Munro, the operation made “its contribution in the long run to protecting the convoy route to Russia and weakening the Germans on the far north flank.”

By the spring of 1942, American staff began arriving in London and soon American and British chiefs were planning landings in North Africa. The British command also had plans for a raid on the French coast at the port of Dieppe. It would later become one of the major Canadian news stories of August and September 1942.

The Dieppe Raid

In 1942, Munro was assigned to report on Operation JUBILEE – known as the Dieppe Raid. He followed the training leading up to the raid and was an eyewitness to the battle on 19 August from one of the many landing craft that took men to the shore at Puys beach. “For eight raging hours, under intense Nazi fire from dawn into a sweltering afternoon, I watched Canadian troops fight the blazing, bloody battle of Dieppe,” he wrote.

On no other front have I witnessed such a carnage. It was brutal and terrible and shocked you almost to insensibility to see the piles of dead and feel the hopelessness of the attack at this point.... They [the Germans] were firing at us at point-blank range.... The way those men stood up and blasted back at the Germans, when they could feel even then that the attack at Puits [Puys] was a lost cause, was one of the bravest things I’ve witnessed.

Once Munro made his way back to London, he filed a number of news reports about the raid, during which 807 Canadian soldiers were killed, around 1,200 wounded and 1,946 taken prisoner. (See Dieppe Raid for more information about casualty numbers.) Munro’s published reports from “Somewhere in England” were received as shocking news to many Canadian readers, especially to those families whose sons had participated in the raid. Before the reports from war correspondents, the Dieppe Raid had been presented as a success.

Shortly after, Munro was sent to Canada on a nationwide lecture tour under the sponsorship of the Canadian Press, speaking at various public rallies in the hometowns of the regiments that fought at Dieppe.

North African Campaign

Following his return to England in the fall of 1942, Munro was assigned to report on the North African campaign. He spent Christmas on a troopship and arrived in Algiers on 2 January 1943. Munro’s reports featured the Canadian troops of the 6th Armoured Division, as well as Canadian Spitfire fighter squadron pilots serving in the Royal Air Force.

By April, Munro had returned to England; on 8 May, he married Helen Marie Stevens from Dunnville, Ontario, whom he had met while she was serving as a nurse in England. Their military wedding plans in the south of England were reported in the Ottawa Citizen and the wedding was featured in a short film clip in a Canadian Army Newsreel.

Sicily and the Italian Campaign

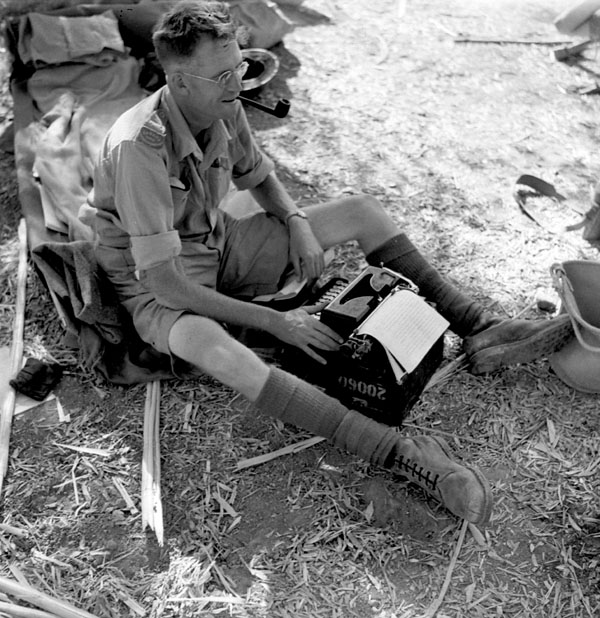

After a brief rest, Munro was assigned as one of the first reporters on Operation HUSKY. He accompanied Canadian and British forces deployed to Montgomery’s Eighth Army and U.S. General Patton’s Seventh Army for a planned invasion of Sicily in July 1943. This was Canada’s first large scale military mission after almost four years in the European theater.

Munro’s reports were the first to reach Canadian readers about the invasion. Besides the obvious dangers, the men also faced the heat of the Sicilian sun and dirt from the chalked dust-filled roads. Munro wrote that,

Like the troops, the correspondents looked like labourers who had slaved a month in a flour mill. We were covered with fine white dust after we had been on the road for half an hour and even when we washed it off we still had a ghostly pallor. Our bush-shirts and shorts and socks were impregnated with dust; we wore goggles and tied handkerchiefs over our mouths as we rolled along in truck, artillery and tank convoys which clogged the highway from dawn to dusk and into the night...... We went for weeks without baths... Fleas and bugs, scorpions and the ubiquitous mosquito were campaign menaces and we religiously followed our anti-malaria rules…to use our mosquito nets every night when we slept and to take our yellow mepacrin pills regularly.

For Canadian troops, the invasion of Sicily totalled 2,310 in casualties, with 562 killed. The RCAF suffered 154 fatalities. Munro also reported on the Italian Campaign, which resulted in more than 26,000 Canadian casualties, including over 5,300 dead. A Canadian Army Newsreel about the campaign featured Munro, who “scooped everyone with his first dispatch” about the taking of the Pachino airfield (the reel also showed CBC reporter Peter Stursberg.

D-Day

Following the Italian Campaign, Munro was assigned to the first wave of troops landing at Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944. His dispatches were the first reports from the coast of France read by Canadians. Following the invasion, Munro reported on the advance of Canadian and Allied troops across northern France into Belgium and the Netherlands. (See also D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, Liberation of the Netherlands.)

By 5 May 1945, Munro found himself in the lobby of a shell-smashed hotel at Wageningen, the Netherlands, where General Foulkes received a formal surrender from Colonel-General Blaskowitz, commander of the German forces in the Netherlands and northwest Germany. Munro reflected, “I watched tired old Blaskowitz sitting across the dusty table from General Foulkes and, blinking like an owl, agree to every surrender term.”

By the next day, Munro was in “Rheims, France, in a stuffy room in a barrack-like school which served as General Eisenhower’s forward headquarters;” in that room, Colonel-General Jodl and General-Admiral Von Friedelburg signed the unconditional surrender for all German forces. The next day was declared VE-Day in Europe. It was also Munro’s second wedding anniversary.

Munro published his wartime memoir Gauntlet to Overlord: The Story of the Canadian Army in the fall of 1945 (a second edition was published in 1972). It won the 1945 Governor General’s Award for English-language non-fiction.

Post-War Career

Munro remained in Europe as a CP correspondent until 1947, reporting to Canadian readers on the Nuremberg trials. He then returned to Canada to become a national correspondent for Southam News Services (see Southam Inc) and later reported on the Korean War (1950–53).

In the ensuing years, Munro served as editor of the Vancouver Province. He was later the publisher of the Edmonton Journal, the Montreal Gazette, and the Winnipeg Tribune. He was also the founding publisher of the Canadian Magazine.

Munro’s wife, Helen Marie Stevens, died in 1981, and he later married Beth Helleur. He retired in 1979 and died in 1990 at the age of 76.

Legacy

In 2002, the Conference of Defence Associations (CDA) established the Ross Munro Media Award, which recognizes “excellence and objectivity in the coverage of national defence and security issues.” In March 2013, the sculpture “WARCO,” depicting Ross Munro, was erected by the Royal Military College of Canada; it is dedicated to “current and past Canadian journalists who cover national defence and security issues.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom