The sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) is the third-largest baleen whale. These whales are found in Canada's Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Two subspecies of sei whales are recognized: a northern subspecies (Balaenoptera borealis borealis) and a southern subspecies (Balaenoptera borealis schlegelii). The sei whale is one of the fastest whales, reaching up to 55 km/h over short distances.

Description

Sei whales have long, streamlined bodies that are steel-grey and lighter on the underside. They are mottled with discoloured spots or swirls and are also often found to have scars from predators and boat collisions. They are 12–15 m long on average but can reach up to 18 m, with females being larger than males. As one of the largest whale species, sei whales weigh between 15 to 20 tonnes on average but they can reach up to 45 tonnes, making them the third-largest whale of the Balaenopteridae family after the blue whale and the fin whale. Their dorsal fin is slender and hooked and helps identify them in the wild. On their pale undersides are 32–60 short pleats that allow sei whales to expand their mouth and throat when feeding. As filter feeders, sei whales have around 600 dark baleen plates with bristles that are much finer than any other species of baleen whale. Sei whales have two blowholes on their backs that produce blows reaching up to 3–4 m in height.

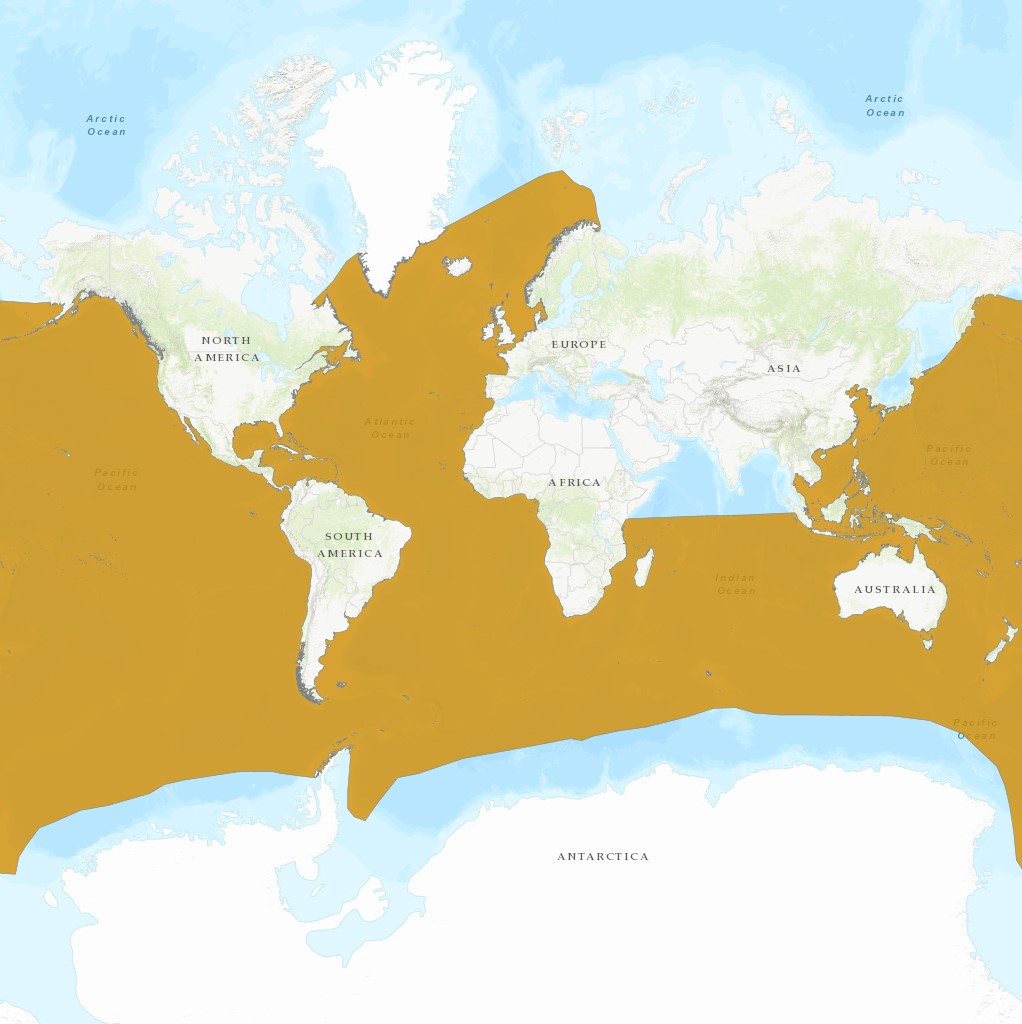

Distribution

Sei whales have a wide range in the open oceans of temperate and subpolar latitudes. They favour cooler waters between 8 and 18°C and avoid warm equatorial waters or freezing polar waters. Sei whales' movement and migration patterns are not well understood, but they are most often seen far offshore, in deeper waters. Unlike many other whale species, sei whales are inconsistent in their migratory patterns. They may be found in abundance in one area and not return for many years. This behaviour is uncommon for large whales, who normally return to the same feeding and nursing grounds yearly. Overall, it is understood that they spend the summer in higher latitudes to feed and spend the winter in lower latitudes, where they raise their young.

Reproduction and Development

Sei whales migrate to subtropical latitudes during the winter to reach their calving grounds. However, the exact location where sei whales give birth or nurse their newborns is unknown. After 11–13 months of gestation, calves are born between 4–5 m long and weigh between 700 and 900 kg. These calves will remain with their mother and depend on her for food throughout the winter and during their spring migration. They are weaned after 6–9 months, once they have reached the summer feeding grounds. From then, the calves will become independent and continue to grow. Sei whales become sexually mature at the age of 5–15 years or when they have reached approximately 12–13 m. Females typically reproduce every 2–3 years and give birth to a single calf or, much more rarely, twins. These whales can reach up to 70 years of age.

Behaviour and Diet

As a part of the baleen whale family, sei whales filter feed on their prey using their baleen plates that allow water to pass through but keep their prey in. However, unlike most baleen whales, sei whales will feed both through “gulping” and “skimming.” Their diet includes fish, squid, krill, copepods and zooplankton; these large whales eat around 900 kg of food daily. Another uncommon behaviour found only in sei whales is that they do not raise their tail or fluke out of the water when they dive. After diving, they can remain underwater for up to 20 minutes to hunt for fish or squid in deeper waters. These whales are most often observed alone but can sometimes be found in small groups of 2–5 whales, and couples have been observed remaining together during the entire breeding season after mating.

Whaling

The threat of whaling only started for sei whales in the 1950s and 1960s. This was due to the depleted populations of blue whale and fin whales being too small to hunt. Sei whales had been observed in similar areas as these endangered whales, so the hunt turned towards them, especially during Antarctic expeditions. During these years of whaling, it is estimated that the population of sei whales was reduced by 80 per cent, with over 2,000 sei whales caught off the coast of British Columbia during the 1960s. Sei whales were not protected by any regulation until 1986, when the International Whaling Commission placed a moratorium that banned the killing of any species of whale to protect the remaining populations. These whales are currently listed as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN Red List). The Canadian Species at Risk Act also classifies the Pacific population of sei whales as endangered. Additionally, Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) has assessed both the Atlantic and Pacific populations as endangered.

Threats and Conservation

Since the moratorium was implemented, the population of sei whales has had trouble recovering to its original numbers. This may be due to the loss of their habitat and fishing grounds. With increased numbers of fishing boats and other marine traffic, the risk of entanglement in fishing gear increases, as does the risk of being struck by a boat. The shipping industry and oil platforms also produce a lot of noise pollution, which is very harmful to these animals because, like all whales, sei whales depend on underwater sounds for communication. Other threats include climate change and pollution, as these may affect water quality and other water features like temperature, acidity and oxygen levels, which can, in turn, impact prey distribution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom