Shawnadithit (also known as Nance or Nancy April), record keeper of Beothuk history and culture (born circa 1800-6 in what is now NL; died 6 June 1829 in St. John’s, NL). Shawnadithit was captured by English furriers in 1823 and later worked as a housekeeper for merchant John Peyton Jr. In 1828, Shawnadithit was brought to Scottish merchant and naturalist William Cormack, who wanted to record information about the language and customs of the Beothuk. Shawnadithit drew maps of Beothuk territory as well as items of Beothuk material culture. While it is popularly believed that Shawnadithit was the last Beothuk, Mi’kmaq oral histories reject that claim. They argue that Shawnadithit’s people intermarried with inland Indigenous peoples after fleeing their homeland. The legacy of Shawnadithit as an important record keeper of Beothuk history and culture remains undisputed. In 2007, the federal government announced the unveiling of a Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque recognizing Shawnadithit’s importance to Canadian history.

Historical Context

Shawnadithit was Beothuk, an Indigenous people of what is now Newfoundland. With the establishment of more permanent European settlement on their territory in the 18th century, the Beothuk increasingly found themselves forced onto smaller areas of land. There, the Beothuk’s access to food and traditional resources was reduced. Tuberculosis, and other diseases brought by the Europeans to North America, significantly reduced the Beothuk population. So too did conflict. In one noted instance in March 1819, Shawnadithit observed European traders capture her aunt Demasduit and murder her uncle, Beothuk chief Nonosabasut, at Red Indian Lake, in the western interior of Newfoundland. (See also Slavery of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Shawnadithit and the Europeans

In April 1823, Shawnadithit, her mother and her sister, all starving, were captured by English furriers at Badger Bay. They were taken to St. John’s by merchant and magistrate John Peyton Jr. There, the women were supposed be placed under the care of Governor Charles Hamilton. However, he was in England at the time of their arrival. Since the women were in poor health, Captain David Buchan, who was acting on Hamilton’s behalf, decided to release them after first ensuring they received medical attention. Given gifts to present to their people — peace offerings — Peyton left them at Charles Brook, located on the western side of the Bay of Exploits and north of Exploits River.

During this time, the health of Shawnadithit’s mother and sister worsened. They soon died, likely the result of complications from tuberculosis. All alone, Shawnadithit was taken into the home of John Peyton Jr. at Exploits. She worked there as a household assistant for five years. English settlers soon renamed her Nance or Nancy April.

Recording Beothuk History

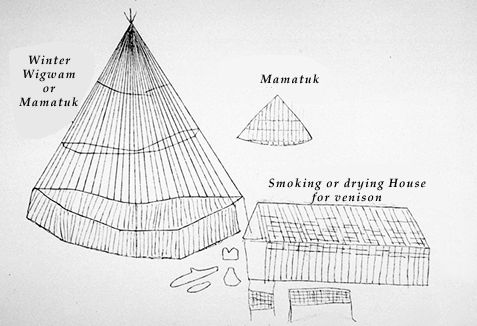

In 1828, Shawnadithit was brought to the Beothuk (then spelled Boeothick) Institution in St. John’s. This was an organization formed the year prior as a means of protecting Beothuk culture. Listening to Shawnadithit speak about her people, the institution’s president, William Cormack, helped her to record valuable information about the language and customs of the Beothuk. Shawnadithit drew valuable sketches of Beothuk settlements, tools, and people, as well as maps of territory. Her record remains an invaluable written record of Beothuk history and culture.

Did You Know?

Artist Gerry Squires created Spirit of the Beothuk (2005), a life-sized bronze statue of Shawnadithit. It stands at Boyd's Cove, in eastern Notre Dame Bay on the northeast coast of Newfoundland.

Death and Legacy

Sick with tuberculosis, Shawnadithit died on 6 June 1829. She was buried in a cemetery in St. John’s.

Shawnadithit’s efforts to preserve Beothuk history and culture are lasting testaments to her people. Her drawings bring Beothuk traditions to life and, at the same time, illustrate the damaging effects of European settlement on those traditions. Shawnadithit’s accounts, as well as those of other Beothuk women, such as Demasduit and Oubee, have enabled others to learn about the Beothuk. Demasduit, Shawnadithit’s aunt, created a Beothuk dictionary, while Oubee, a Beothuk girl captured in 1791, left accounts of her people’s culture and beliefs.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom