Forty years ago, Canada opened its doors to its first wave of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. After American troops withdrew from Vietnam in March 1973, continental Southeast Asia (former Indochina) was left to the mercy of revolutionary forces in the region. When it became clear that Communists from North Vietnam would invade the South, many Vietnamese tried to escape the country. Canada admitted 6,500 of these political refugees in 1975–76.

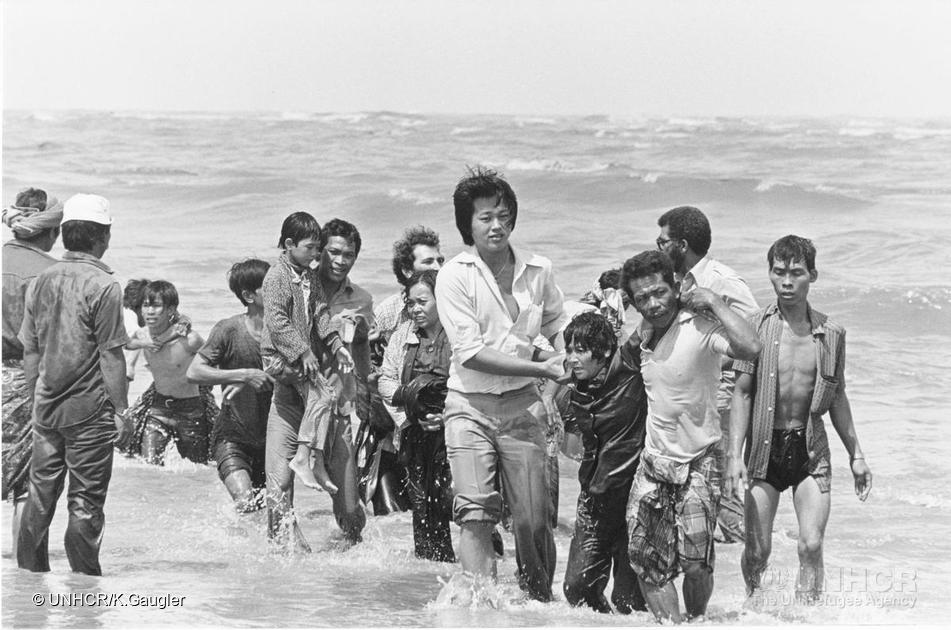

A second wave began in 1979 with the arrival of a group of South Vietnamese refugees who had suffered under the horrendous conditions imposed by the new regime. Moved by the desperate plight of the hundreds of thousands who, to escape the Communist regime, took to the high seas in makeshift boats that threatened to sink at any moment, many Canadians offered to sponsor their journey to Canada. The government permitted an initial contingent of 60,000 refugees to enter the country. Among them were many Cambodians and Laotians who had set out over land or sea to escape their countries, which had fallen under the control of the Khmer Rouge and the Pathet Lao.

On 13 November 1986, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) recognized the generous and unprecedented welcome Canadians extended to these refugees when it awarded the Nansen Medal to the “People of Canada.” It is the only time the honour has been bestowed on an entire population.

Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians gave back to their adopted country, enriching Canadian society in many different ways. In this exhibit, we seek to tell their story and highlight their contributions, all while examining Canada’s complex history surrounding its treatment of refugees.

When I saw my first snowbanks through the porthole of the plane at Mirabel Airport, then too I felt naked, if not stripped bare. In spite of my short-sleeved orange pullover purchased at the refugee camp in Malaysia before we left for Canada, in spite of my loose-knit brown sweater made by Vietnamese women, I was naked. Several of us on the plane made a dash for the windows, our mouths agape, our expressions stunned. After such a long time in places without light, a landscape so white, so virginal could only dazzle us, blind us, intoxicate us. ‒ Kim Thúy, Ru (2012)

What Is a Refugee?

"Asylum seekers are people who have moved across an international border in search of protection under the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention), but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been determined."

— International Association for the Study of Forced Migration (IASFM)

A refugee is a person who flees his or her home country to escape persecution or danger and seek safety elsewhere. Canada is a country with a long tradition of welcoming refugees and asylum seekers from all over the world. However, this history is checkered with differing policies that impact the way refugees are treated in Canada and continue to affect thousands of people seeking refuge. Refugee policies are also impacted directly by popular opinion, current governments and media discourses.

Canada’s First Refugees

The United Empire Loyalists are regarded as among Canada's first refugee contingents. However, most were not refugees under the modern definition, but instead were British settlers. Among them were some who would be termed refugees, mostly Quakers, Mennonites and other nonconformists who feared persecution by the new American government and fled northwards. Before 1860, thousands of fugitive American slaves also arrived in Canada, and the public recognition given to Canada as the final stop on the Underground Railroad reaffirmed that this country was indeed a sanctuary for those seeking protection from persecution. An estimated 30,000 African Americans came to Canada seeking protection.

Over the next generation, two groups of refugees, Mennonites and Doukhobors, arrived from Russia in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Both groups were persecuted under the Russian tsars. The Canadian government was searching desperately for farmers to populate the West and resettled these groups mainly to the Prairie Provinces.

Policies of Exclusion

Not all migrants were similarly welcomed in Canadian society. Through policies such as the Chinese head tax at the turn of the century, as well as Japanese internment during the Second World War, certain groups of migrants were selectively excluded. Canada also turned away ships bearing refugees, such as the 376 passengers, most of whom were Sikhs, on the SS Komagata Maru in 1914, which was not allowed to dock in Vancouver.

A major test for Canada in defining itself as a country of refuge for the persecuted occurred in the 1930s, when German Jews were seeking admission to any country that would receive them. However, Canada's borders were not open. Xenophobia and anti-Semitism permeated Canada, and there was little public support for, and much opposition to, the admission of refugees. In fact, this attitude of exclusion did not change until after the Second World War. With Europe full of "displaced persons," Canada became much more receptive, largely due to its booming economy and the necessity to increase its workforce. Canada also began to play an increasingly active role in resettling refugees through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

A Change of Course: Refugees of the Cold War

In 1956, within months of the Hungarian uprising against the Soviet occupation, the Canadian government succumbed to domestic pressure, especially from ethnic and religious groups, and announced that it would accept a large number of Hungarian refugees. Almost 37,000 arrived. Not only did these refugees bring some badly needed skills, but their acceptance while Cold War tensions and anti-communism were rising, provided the West with an opportunity to embarrass the Soviet Union. In 1968, 11,000 Czechs, following the Soviet invasion of their country, settled in Canada. Most were highly skilled and integrated rapidly into Canadian society. In 1972, Canada also accepted 7,000 highly trained and educated Ugandan Asians who were fleeing the notoriously repressive regime of Idi Amin (see African Canadians).

A more controversial group of refugees were the American war resisters (or "draft evaders"), who fled across the border to escape service in the Vietnam War. Equally controversial were the Chilean and other Latin American refugees forced out of Chile by the September 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende's Marxist government by Augusto Pinochet's coup. Fearing that most of these political refugees were too left wing, and not wishing to alienate either the American or new Chilean administrations, the Canadian government restricted the numbers.

This is in sharp contrast to Canada's humanitarian action during the Vietnamese "boat people" crisis of the late 1970s.

Changing Policies and Laws

In 1962, a Canadian government order officially abolished racial discrimination in the selection of immigrants (see Immigration Policy). In April 1978, the new Immigration Act came into effect and established four new classes of immigrants who could come to Canada: refugees; families; assisted relatives; and independent immigrants who were coming to Canada for economic reasons.

The Immigration Act was also amended to avoid any explicit mention of preferred nationalities of migrants. This law also adopted the comprehensive definition set out in the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, which are the main international legal instruments governing the protection of refugees. Article 1 of the Convention defines a refugee as a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is unable to return to their country of origin.

Refugees from Southeast Asia

The Vietnam War ended on 30 April 1975 with the fall of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, to Communist forces. By the end of the year, totalitarian and Communist regimes ruled former Indochina. Cambodia fell entirely under the power of the Khmer Rouge on 17 April 1975, when the revolutionary organization took the capital, Phnom Pehn, and other cities. In Laos, the Communist revolutionaries of the Pathet Lao, which had taken power earlier in the year, abolished the monarchy on 2 December 1975 and proclaimed the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

In Vietnam and Laos, former civil and military officials were sent to labour camps and their families were refused access to employment and education. In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, led by the ideologue Pol Pot, abolished private property, forced the majority of the population to live in rural labour camps, and persecuted ethnic and religious minorities. At the end of 1978, an armed conflict broke out between Vietnam and Cambodia, adding to the distress of their populations.

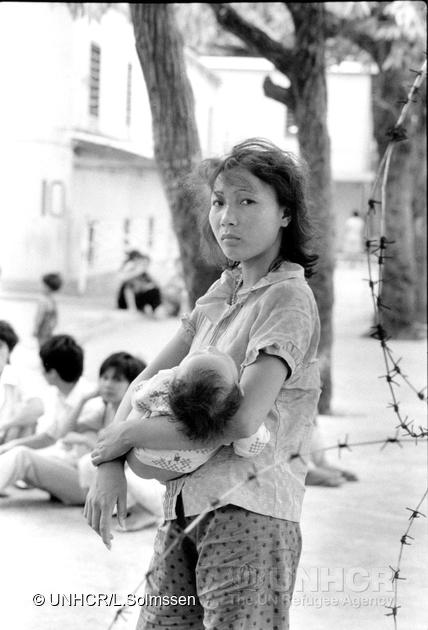

The political context, human rights violations and rapidly deteriorating living conditions in these countries set off an unprecedented migration in Southeast Asia. Following the invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam, many thousand people left Cambodia on foot for Thailand. The exodus of Vietnamese and Chinese from Vietnam began to take on dramatic proportions in late 1978, when several thousand people left the country in makeshift boats via the China Sea. The “boat people” who survived this treacherous voyage were admitted into HCR camps in Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Hong Kong.

Canada Extends Welcome

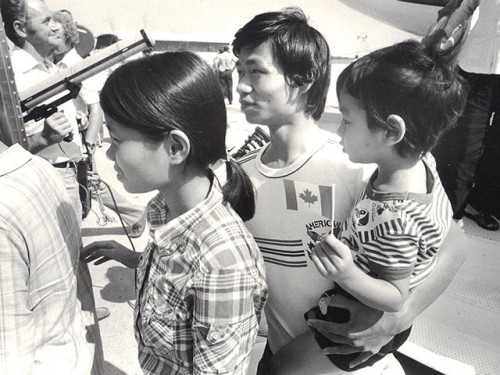

Moved by these exiles’ plight, Canada reacted swiftly and played a major role on the international stage. In July 1979, the HCR organized a meeting in Geneva about the admission of Southeast Asian refugees. The Canadian government, led by Prime Minister Joe Clark, participated, and Clark announced that Canada would admit 50,000 refugees. By the end of 1979, Canada had chartered 76 flights and transported 15,800 people. In April 1980, the government revised the target number of people it would admit and announced that Canada would accept 10,000 more. This brought the number of refugees to 60,000 for the year 1979–80.

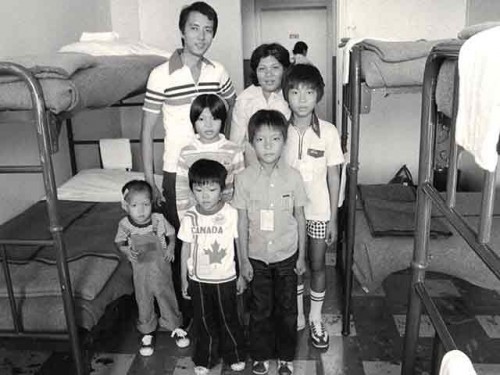

More than 50 per cent of these refugees came to Canada as a result of a brand-new private sponsorship program put in place by the government. It was therefore in large part due to the efforts of Canadian families, religious communities, charitable organizations and non-governmental organizations that these people had the opportunity to rebuild their lives in Canada. By 1985, Canada had admitted more than 98,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. This placed it among the top five countries to admit Southeast Asian refugees.

By the Numbers

From 1981 to 1986, many Southeast Asians continued to immigrate as refugees and designated-class immigrants: 24,000 from Vietnam, 3,400 from Laos and 8,900 from Cambodia. At the end of 1986, 130,000 Indochinese, or 95 per cent, were immigrants: 100,000 from Vietnam, 14,000 from Cambodia and 15,000 from Laos. Efforts by Southeast Asians in Canada to reunite their families from 1987 to 1996 increased the immigrant population by 50 per cent.

In response to the 2011 National Household Survey, 220,425 people declared their ethnic origin as Vietnamese, 34,340 declared Cambodian (or Khmer) origin and 22,090 declared Laotian origin. In addition, several tens of thousands of Canadians who declared Chinese origin actually arrived from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Like 91 per cent of the foreign-born population, most Southeast Asian immigrants settled in Canada’s metropolitan areas and urban communities.

In Their Own Words: Starting a New Life

I was as suprised by all the unfamiliar sounds that greeted us as by the size of the ice sculpture watching over a table covered with canapés, hors d’œuvre, tasty morsels, each more colorful than the last. I recognized none of the dishes, yet I knew that this was a place of delights, and idyllic land. (…) I now had no points of reference, no tools to allow me to dream, to project myself into the future, to be able to experience the present, in the present. ‒ Kim Thúy, Ru (2012)

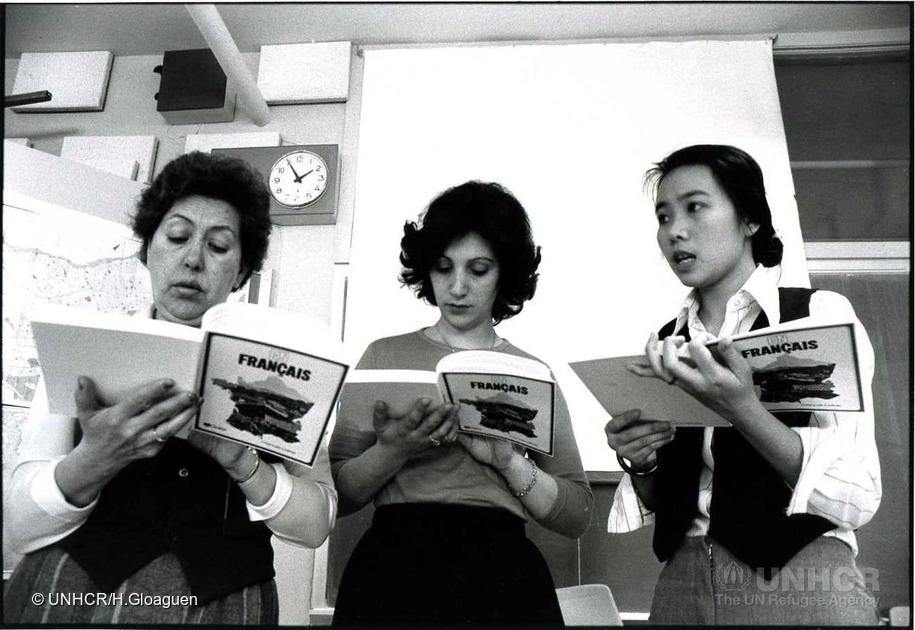

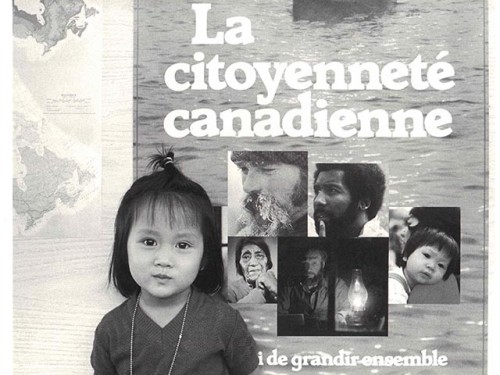

The journey of Southeast Asian refugees did not end upon their arrival in Canada. While those with more education might know French or English, most had to learn not only a new language, but also new cultural codes. Integration into Canadian society was not easy. The stories of various Passages Canada speakers serve as a testament to the challenges encountered by these immigrants.

Minh Tan endured a difficult crossing to Malaysia and harsh conditions in a refugee camp to finally discover a world of possibility in Canada. For Tu Nguyen, who was sponsored by her father as an adult, immigrating meant losing the position she’d achieved as a journalist and restarting her career from nothing. Today, she seems to have found her way, accompanying young immigrants as they integrate into Canadian society. Vilien Chen talks about the difficulty coming to terms with the “refugee” label and the time it took her to find the strength to reconnect with her family history.

Tu Nguyen

Canada chose me. I came to Canada under my father's sponsorship. He was one among thousands of Vietnamese boat people who escaped the communist government in the 1980s.

I still remember the first day arriving at the Calgary airport. A cold and snowy November night. The snow and quietness did not look and feel as poetic and beautiful as I had imagined when I was in Vietnam. I almost burst into tears when a custom's officer asked me some questions. I had no idea what he was saying. Then I looked at some English signs around, and couldn't figure out what they meant. Only that moment I bitterly realized that my life would never be the same any more. An established journalist and writer for 10 years in Vietnam, now I became nobody in Canada.

All the jobs I did in the first few years were labor jobs. Nanny, office cleaner, factory worker, you name it. I remember often sobbing in the quiet nights, wondering if it was a terrible mistake leaving my country, and if I would be able to survive in the new land.

Yes, I've been through all the challenges and confusions of a newcomer, trying to make a success in a strange culture so vastly different from my own. I consider myself to be very fortunate to be involved with the Calgary Bridge Foundation for Youth for the past 10 years. This work is very challenging but rewarding. It has given me the opportunity to meet with hundreds of new young immigrant students who came from all corners of the globe. Many of them came to Canada with little English and few life skills, and are at risk of dropping out of school. Also they experience a great deal of racism in school, from name calling to racist actions and negative comments on their culture. Through our various after-school programs, we are able to keep them away from gang or drug-related activities, and help them further their education in Canada. It just blows me away every time learning about how I could make an impact in the life of immigrant youth who need to have someone walk with them when they are at a difficult point in their lives.

I have been in Canada for 12 years now. I cannot tell when I started feeling that this country became my new home. There have been times I was waking up in the middle of the night with an inexplicably melancholy feeling. I seemed to hear the waves washing up on the shore back in my homeland. My past has often come back to haunt me. The childhood in a small poor village with the dream of having a Barbie doll that can open and close her eyes, and the many nights spent in the bomb shelters dream sleeping in the sounds of bombs and canon, and the feeling of the earth shaking...

I still miss writing, and hope one day to be able to write about the life of new immigrants in Canada.

Vilien Chen

I wish I could tell you my first experience arriving in Canada, but I have no recollection of it at all. That was the summer of 1979. I was three at the time. My parents have always told me not to let others know that we were refugees from Vietnam. They believed that Chinese people would look down on us if they knew. They also would like me to make it a point that they did not take a single penny of welfare money from the government. For some reason, that was important for them.

Even today, the word “refugee” sounds dirty to me. I was always taught not to talk too much about my past, and if people asked me where I was born I should just say that I grew up in Canada. It was important that I not talk too much about my family’s past with others, probably because they could pinpoint where we came from, and that would bring shame to our family.

Ten years ago it was my graduation from school. By chance, perhaps, my parents decided to return to Vietnam. They asked me if I would like to go as well. “You could see the place where you were born,” they said. I didn’t want to go. I had no real interest in returning. I would have much rather preferred to hang out with my friends. That trip could have been my graduation present. I remembered around that time as well my grandfather would constantly ask me if I had free time, and that if I did, he would bring me back to Hokkien – the home of my ancestors. I never did get that chance to return with my grandfather.

This summer, exactly ten years later, my mother and father planned again to return to Vietnam. This time I really, truly wanted to go with them. This time I felt it was the right time. The first glimpse I had of my grandfather’s place in Vietnam, it wasn’t our home anymore. My dad thinks that it may have been rented out by the government. When I saw that pale blue and grey apartment, there was a small child sitting on the top balcony floor. Had my mom and dad not escaped to Canada, perhaps my life and my future would be like that child’s.

13 November 1986: The Nansen Medal

In 1986, in recognition of its exceptional contribution to refugee protection, Canada was awarded the Nansen Medal by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Governor General Jeanne Sauvé accepted the honour on behalf of the “People of Canada.” The medal is kept at Rideau Hall.

In 2015, the Parliament of Canada passed the Journey to Freedom Day Act, which designated 30 April as a national day of commemoration of the exodus of Vietnamese refugees and their acceptance in Canada after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War.

The Canadian Encyclopedia would like to thank Passages Canada, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and The Canadian Immigration Historical Society for granting us permission to reproduce stories and photographs from their collections.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom