Early Years

Stanley Grizzle was born in Toronto to Theodore Grizzle and Mary Sinclair Grizzle. He had three sisters and three brothers. His parents both moved to Canada from Jamaica in 1911; they met and married in Toronto. Mary arrived as a domestic and Theodore got a job as a chef for the Grand Trunk Railway. Theodore eventually established a thriving taxi company, but fell on hard times during the Great Depression.

In 1938, Stanley Grizzle helped establish the Young Men’s Negro Association of Toronto, where he began his fight for the rights of Black Canadians.

In his memoir, My Name’s Not George (1998), Grizzle describes a fulfilling youth spent listening to jazz music with his family, participating in church and community activities, playing sports in local clubs, and yearly celebrations of Emancipation Day.

Railway Porter and Labour Leader

Although Stanley Grizzle’s parents wanted him to continue his studies after high school, it was difficult for them to come up with the money to send Stanley or his six siblings to college or university.

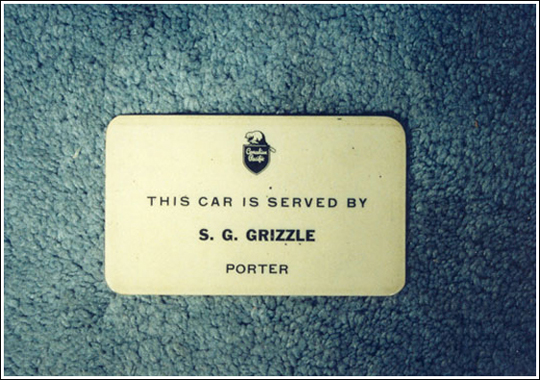

In June 1940, when he was 22, Grizzle began working as a sleeping car porter with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) — the only job that was hiring Black men at the time. Grizzle started out as what was called an “extra,” filling in for porters who were on sick leave. Making beds, cleaning toilets and shining shoes were just some of the tasks that railway porters had to do as part of their jobs. One demeaning aspect about being a porter for Canadian Black men was that many of the White passengers would call the porters “George,” after George Pullman, inventor of the Pullman sleeping car, rather than calling them by their names. It was only after the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) negotiated with the CPR that every porter would get two plastic name cards to encourage passengers to call each porter by his name.

Grizzle worked as a porter for the CPR for 20 years. In that time, he also advocated and negotiated better working conditions for porters. He was elected president of the Toronto CPR division of the BSCP in 1946.

In the early 1950s, Grizzle became a member of the Joint Labour Committee to Combat Racial Intolerance. He was also instrumental in leading groups to meet with provincial and federal leaders to discuss anti-discrimination legislation for Black Canadians. Grizzle frequently appeared on tv and radio to discuss and explain the many issues that were plaguing the Black community in Canada.

Military Career

In 1942, Stanley Grizzle was conscripted into the Canadian army. Although he understood the reasons for the Second World War, he was bothered by the fact that Canada was fighting for democracy in Europe, but was not extending that same democracy, fairness and equality to Black Canadians at home.

While serving in England, Grizzle was assigned duties as a “batman,” shining shoes and tidying officers’ quarters. He refused this work because he found it demeaning and racist (Black servicemen were routinely assigned such duties). Years later, he recalled telling his superior, “Sir, I realize that the only time you have seen a Black man has been as a servant, but I don't think it’s very democratic.” Grizzle was punished with latrine duty for his refusal and went on strike. After making his stand, Grizzle was reassigned and promoted to corporal.

In February 1946, Grizzle returned home and was discharged from the army. He went back to work as a porter and enrolled in courses in labour, economics and public speaking at the University of Toronto.

Political Career

After his time in the army, Stanley Grizzle continued to fight for the rights of Black Canadians. At the time, Canadian immigration policy restricted, and in some cases denied, equal immigration status to British Commonwealth applicants from the Caribbean, British Guiana (Guyana), India, Pakistan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and African countries who were trying to immigrate to Canada and gain citizenship (see Immigration Policy in Canada). Canada only wanted applicants who were from the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa.

On 27 April 1954, Grizzle was part of the first delegation of Black Canadians to meet with members of the federal Cabinet to discuss Canada’s discriminatory immigration practices.

A few years later, in 1959, Grizzle and another man, named Jack White, became the first Black Canadians to attempt to gain seats in the Ontario legislature. Although he gained just over 9,000 votes as a Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) candidate, Grizzle finished third in his riding.

In the early 1960s, Grizzle was hired as a clerk of the Ontario Labour Relations Board, making him the first Black Canadian to work at the Ontario Ministry of Labour. He was later promoted to officer.

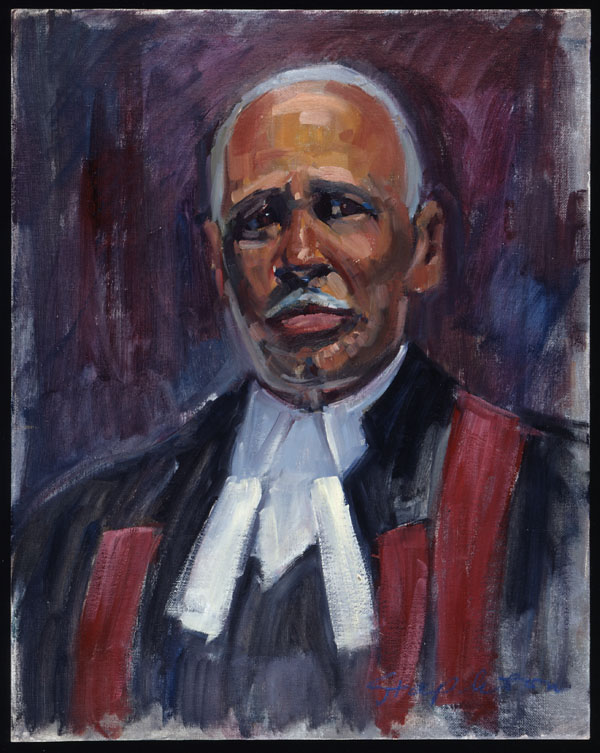

Grizzle remained on the Labour Relations Board until Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau appointed him as a citizenship court judge. Grizzle was the first Black Canadian citizenship judge.

Personal Life

When he was in the military, Stanley Grizzle met Kathleen (Kay) Victoria Toliver, of Hamilton, Ontario. They were married in September 1942, while Stanley was on a two-week leave from service duties. Kay was a founding member of the Canadian Negro Women’s Association.

Stanley and Kay had six children and one foster son. Grizzle had 14 grandchildren, as well as several great-grandchildren.

Legacy and Significance

In 1998, Stanley Grizzle published his autobiography, My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada, Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle.

In 2007, Grizzle donated his personal papers — which include news clippings, speeches, photographs and countless scraps of information on Black Canadian life — to Library and Archives Canada.

That same year, a park in the east end of Toronto was named in Grizzle’s honour (2007). In 2018, a Toronto laneway was also named after Grizzle.

Honours and Awards

- Order of Ontario (1990)

- Canadian Labour Hall of Fame (1994)

- Member, Order of Canada (1995)

- Recipient, Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal, Government of Canada (2002)

- Lifetime Achievement, Harry Jerome Awards (2010)

- Recipient, Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal, Government of Canada (2012)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom