Wartime Sacrifice

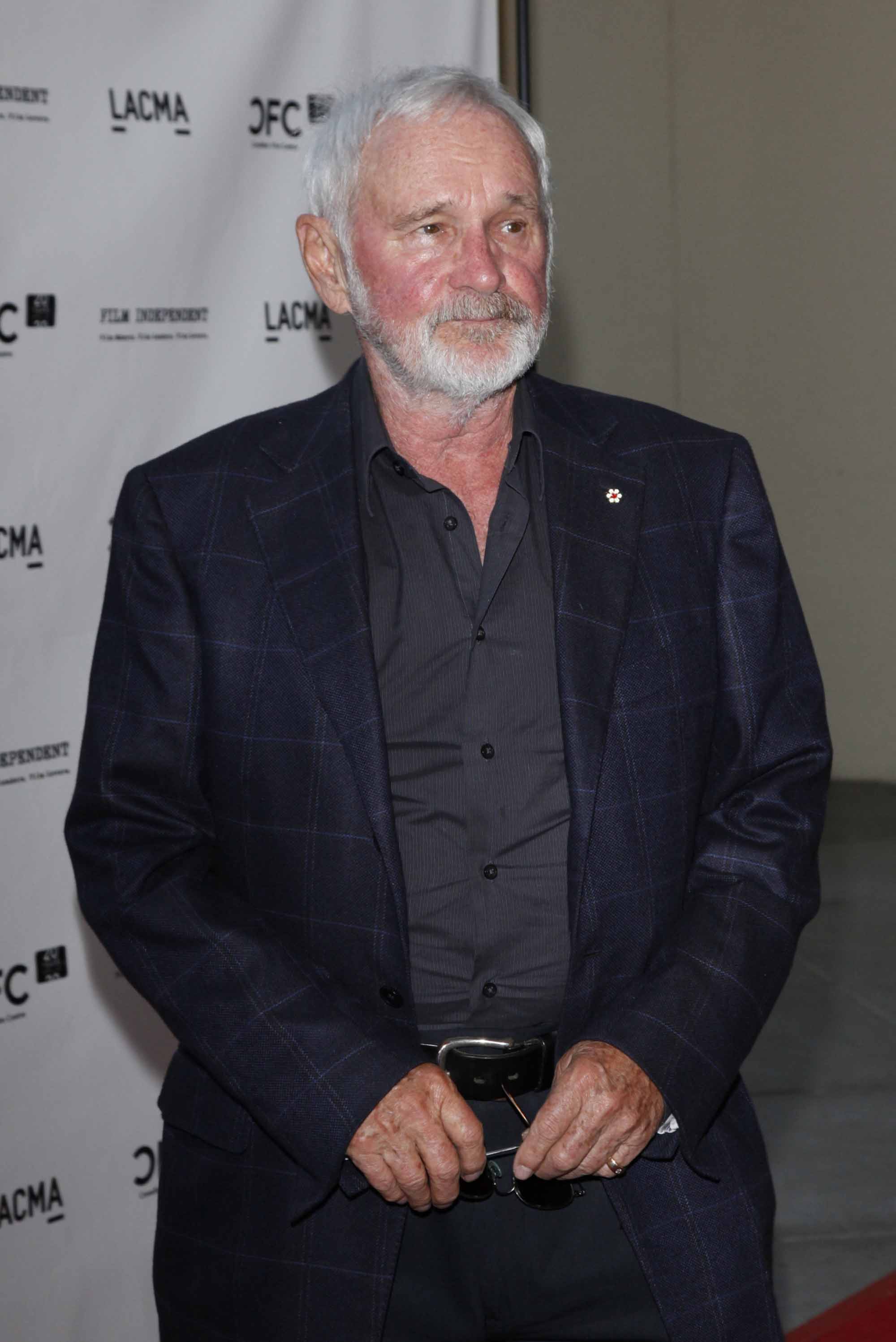

Norman Jewison built his career amid the glitter, ego and abundance of Hollywood. Yet

By the time Jewison was 13, the Second World War was underway and all of

"The whole production of the country, from food to material to clothing, everything was being built and focused toward the war," he says. "There weren't even silk stockings, so women were painting their legs. It was unbelievable. Everybody was involved and totally committed to winning this war and supporting the troops. I've never seen a society so focused.

"I look around today and think how long ago it was," he says at 78, gazing out the windows of his sunlit

Joining the Navy

Jewison's relatives almost all served as army reservists during the war. His uncle Charlie was a sergeant major in the 48th Highlanders, and his father was a sharpshooter with the Queen's Own Rifles. Jewison, however, had joined the Sea Cadets in high school — "one way to get the attention of girls" — and at 17 he volunteered for the Royal Canadian Navy.

After basic training in

The war was in its final months by the time Jewison made it to sea, working as a signalman on a Canadian corvette, escorting merchant ships up the east coast from

The

"I was disappointed that I never got to cross the

The U-boats, however, were still sniffing around American and Canadian ports, occasionally sinking ships in the

But his only glimpse of the enemy came after

Confidence in Ourselves

Jewison eventually came back to

By the time he returned to

"[The Second World War] was when

"

"But look at what we've done in history, with so few people. Look at what we accomplished in that war.

"I think that's what we need again today — confidence in ourselves."

Years ago, Jewison took his then-teenage sons to

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom