Early Life

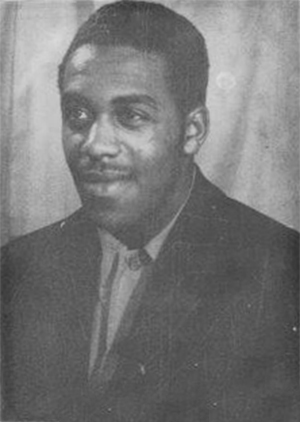

Ted King was born in Calgary to John and Stella King. He had three siblings, Vern, Lucille and Violet, who would go on to become the first Black person admitted to the Alberta Bar, and the first Black female lawyer in Canada. John King worked as a sleeping car porter with the Canadian Pacific Railway and Stella worked as a seamstress.

King’s family moved to Canada in 1911 from Oklahoma. They first moved to the all-Black settlement of Keystone, Alberta. This followed a wave of other Black settlers who came to the province for newfound freedom and economic opportunity (see Black Canadians). When they arrived, they initially faced racist barriers, including the attitude of some politicians; one well-known declaration against Black immigration came in a Conservative MP’s speech, entitled, “We Want No Dark Spots in Alberta.”

DID YOU KNOW?

Order-in-Council P.C. 1324 was approved on 12 August 1911 by the Cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier. The purpose of the order was to ban Black persons from entering Canada for a period of one year because, it read, “the Negro race… is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” The order-in-council never became law, but the actions of government officials made it clear that Black immigrants were not wanted in Canada.

After graduating high school, King joined the Canadian military and was stationed in England at a postal station, from 1943 to 1946 (see Second World War). Before he left for England, he met Della Mayes at a Black-owned business in Calgary called the “Chicken Fry.” The couple married after King returned from England, on 18 August 1947.

Once discharged, King went to work as a porter for the Canadian National Railway, and then for the Canadian Pacific Railway. A porter was somebody who took care of passengers on trains. This was one of the few occupations available to Black Canadian men. Black porters had to fight to form their own union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, after being denied representation by the white union.

King worked as a porter from 1946 to 1953. During that time, he went to night school at the University of Calgary and attained an accounting diploma. He moved on to work for a farm machine company as their bookkeeper.

Civil Rights

By the mid-1950s, Ted King was involved in the Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (AAACP). He became president in 1958 and served in that position until 1961.

According to King, the purpose of the AAACP was to “promote goodwill and to seek equality in social and civic activities throughout Alberta.” This was done by fighting against discrimination along with hosting social events for the province’s Black community.

King’s process for resolving discrimination complaints was simple. He would first contact those accused of racial injustice, explain who he was, and see if the problem could be resolved informally. If not, King was not afraid to use his community connections and “seek support from some of the important citizens here in Calgary and some of the associations that [they] belong to.”

King was well aware of the injustice and prejudice that Black Albertans faced — discrimination was all too personal for him. When he and his family first moved to the West Hillhurst area of Calgary in 1953, a neighbour petitioned against them moving in. However, nobody signed the petition and that neighbour moved away in protest. The Kings were the first Black family to live in the west-side neighbourhood.

DID YOU KNOW?

Violet King, Ted’s sister, was the first Black person to obtain a law degree in Alberta (1953), the first Black person admitted to the Alberta Bar and the first Black female lawyer in Canada (1954). Violet was also the first woman appointed to an executive position with the YMCA in the United States.

Court Case

On 13 May 1959, Ted King was looking for a friend who was staying at the Barclay’s Motel in Calgary. When he called the hotel, the owner, John Barclay, picked up the phone and denied that anyone by that name was staying there. King then started describing his friend but was promptly told that they “don't allow coloured people.”

After this encounter, King went to the hotel to book a room in order to confirm that this policy existed. He was promptly denied accommodation. King brought his case to the local media and decided to launch a legal challenge against the discriminatory policy.

King based his case on the Innkeepers Act, which said that inns were required to serve any traveller. In turn, the lawyers for Barclay’s Motel denied all charges and claimed that the action had no grounds since King was not from out of town (and therefore not a traveller), and that Barclay’s did not qualify as an inn because it did not serve food.

On 7 April 1960, the case was decided by Judge Hugh Farthing of the Southern Alberta District Court. Farthing reviewed the evidence and while he found King’s case compelling, he was forced to dismiss it. Farthing based his decision on technicalities in the Innkeepers Act and ruled that Barclay’s was not protected by the legislation since the motel did not serve food and was not considered an inn. In addition, despite the fact that Barclay’s allowed local residents to stay there, the judge ruled that King was not a traveller and had no right to accommodation. The judge also added that he did not appreciate that King’s lawyer had publicized the lawsuit.

Appeal and Aftermath

Ted King appealed the decision to the Alberta Supreme Court, with the case being heard on 14 February 1961. The court maintained the ruling, with all judges deciding again that King was not a traveller. In addition, four out of five judges upheld that Barclay’s did not qualify as an inn because it did not serve food.

The judges expressed their displeasure of King’s efforts to use the courts to effect social change.

Despite losing the case, King was able to make an impact. In 1961, the Alberta Legislature closed the loophole in the Innkeepers Act by eliminating the requirement that an inn offer food. In addition, they added a section to the legislation that said a motel could remove a guest if they were causing a disturbance.

Later Life

Ted King was disappointed that he lost the case, in part because of the time he spent preparing. However, he felt satisfaction when the Alberta Legislature closed the loophole that was the major reason for the loss.

In 1963, King moved to join his employer’s expansion to British Columbia, settling in New Westminster. In the early 1970s, he started his own practice and continued working as an accountant.

In 1975, King and his family moved to Surrey, where Ted continued to work as an accountant. Ted believed in lifelong learning and decided to go to school for real estate. In 1978, he got his real estate license. After graduating, he worked for Royal Trust and, in the 1980s, he opened his own firm, called Galaxy Real Estate.

King stayed in real estate until he retired in 1992. However, he worked part time as an accountant during retirement. King enjoyed travelling, coaching sports and music. He was devoted to his family and his grandchildren who are now mainly based in British Columbia.

Ted King died on 7 July 2001. He was cremated in 2002 and buried with his parents in Calgary. King is survived by his wife, Della, and his children, Richard, Linda and Brian.

Significance and Legacy

Ted King’s story fits within Alberta’s long and largely unknown civil rights history. He built on the work of Black Albertans such as Lulu Anderson and Charles Daniels, who fought against discrimination decades before the civil rights movement would peak internationally. Anderson and Daniel fought discrimination at Edmonton and Calgary theatres.

The publicity of King’s case, along with the legislative changes that followed, meant that Black people would no longer be refused lodging due to the colour of their skin. If that were to happen, then they could bring their case to the court and win, thanks to the loopholes that King exposed.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom