The temperance movement was an international social and political campaign of the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was based on the belief that drinking was responsible for many of society’s ills. It called for moderation or total abstinence from alcohol. This led to the legal prohibition of alcohol in many parts of Canada. The Canada Temperance Act (Scott Act) of 1878 gave local governments the “local option” to ban the sale of alcohol. In 1915 and 1916, all provinces but Quebec prohibited the sale of alcohol as a patriotic measure during the First World War. Most provincial laws were repealed in the 1920s in favour of allowing governments to control alcohol sales. Temperance societies were later criticized for distorting economic activity, and for encouraging drinking and organized crime.

Temperance Societies

The first temperance societies in Canada appeared around 1827 in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, and in Montreal. The groups initially tolerated moderate use of beer and wine. This concession continued in Quebec; but it soon gave way in the rest of the country to calls for total prohibition of all alcohol. Groups that promoted temperance, abstinence and prohibition were all commonly referred to as temperance groups.

Temperance activists and their allies believed that alcohol, especially hard liquor, was an obstacle to economic success; to social cohesion; and to moral and religious purity. The Temperance struggle was connected to other reform efforts of the time, such as the women’s suffrage movement. It was also motivated in part by Social Gospel beliefs.

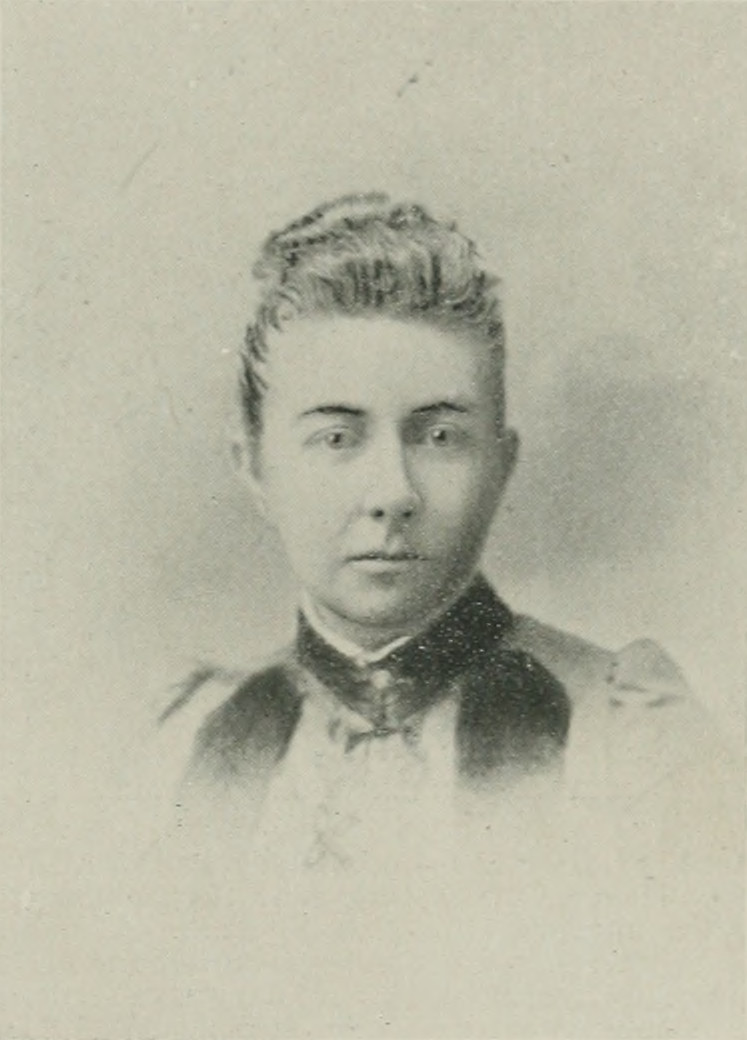

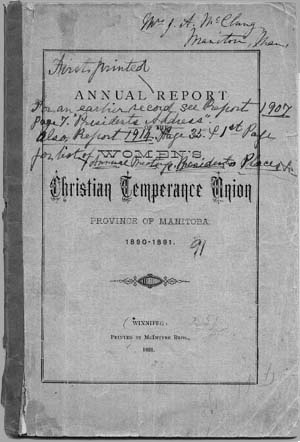

Around 1848, the Sons of Temperance lodge, a fraternal and prohibitionist society, reached Canada from the United States. Other such lodges were the Royal Templars of Temperance and the International Order of Good Templars. The most important temperance society for women was the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, an American group. Its Canadian counterpart was founded in 1874 by Letitia Youmans of Picton, Ontario. It was one of the few organizations through which women could play a political role.

In 1875, the hundreds of societies, lodges and church groups committed to prohibition met in Montreal to form a federation. It was called the Dominion Prohibitory Council. A year later, it was renamed the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic. It became the major organizing force for prohibition campaigns in Canada. The predominantly English-speaking, Protestant alliance discouraged francophone and Catholic participation. Catholics, particularly francophone Catholics, saw prohibition as an extreme measure. La Ligue Anti-alcoölique was formed in 1906 as a French-language counterpart of the Dominion Alliance. It supported legal restriction of the liquor trade, but not full prohibition.

Banning Alcohol by Vote

Jurisdiction over the liquor trade was shared by governments. (See Distribution of Powers.) The provinces could prohibit retail sale. The federal government could ban the manufacturing of alcohol as well as retail, wholesale and interprovincial trade.

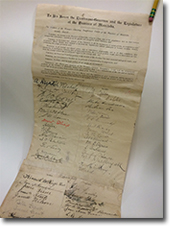

However, governments at neither level were enthusiastic about prohibition, since it would cause a loss of tax revenue and party support. Both levels put forward compromise legislation known as “local options.” Local governments were allowed to hold popular votes to create laws on contentious issues in their areas. The process was enshrined in the Canada Temperance Act of 1878, also known as the Scott Act. It gave local governments the right to hold votes to ban the sale of alcohol. A side effect was to give prohibitionists political experience, through organizing local-option and referenda campaigns. Prohibitionists secured a major victory in 1901 when Prince Edward Island outlawed the retail sale of alcohol.

Prohibition as a War Measure

When the First World War broke out, the temperance movement was close to its peak. Alcohol consumption, though beginning to rise after a half century of decline, was relatively low; organization and funding for the movement were substantial; and local governments widely banned alcohol through local-option votes. At the start of the war, the Dominion Alliance successfully campaigned for prohibition as a patriotic measure, to preserve time and money for the war effort. In 1915 and 1916, all provinces but Quebec prohibited the sale of alcohol. Quebec banned retail sale of distilled liquor in 1919, but only briefly.

Prohibition as a wartime measure was short-lived. A federal ban on manufacturing, importing and selling alcohol expired soon after the war ended. Most provincial legislation was repealed in the 1920s in favour of allowing governments to control alcohol sales. PEI was the last holdout. It prohibited alcohol sales until 1948.

Meanwhile, Canadian liquor interests found a large market in the United States. It was under federal prohibition from 1920 until 1933. A Canadian law rooted in the Prohibition-era, the 1928 Importation of Intoxicating Liquors Act, remained intact until 2012. It was then amended by the federal Parliament to allow consumers to bring limited amounts of alcohol across provincial boundaries for personal use.

The Downfall of the Movement

There are several theories about why the temperance movement waned and prohibition laws failed: they were criticized for distorting economic activity; for encouraging drinking (the opposite of their intended effect); and for encouraging organized crime. Perhaps more likely, there were changes in Canadian society and within the temperance movement itself that likely led to its downfall.

Self-employed Canadians who saw temperance as an aid to economic success were a diminishing part of the population. They were displaced by urban, wage-earning workforces. Within the movement, prohibition had provided an opportunity for close study of urban problems. This led many to conclude that those issues had more to do with the political and economic system than with alcohol. Many left the movement for other forms of activism.

It had been thought that the extension of voting rights to women (see Women’s Suffrage) would sustain prohibition; since it was believed that women were sympathetic to the cause. However, referenda of the 1920s, in which women had the vote, showed a consistent decline of support for prohibition. The temperance movement was the creature of a society that was already fading when its prohibition victories were won.

See also Letitia Youmans; Amelia Yeomans; Louise McKinney; Edith Archibald.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom