March 6, 1834 marked the founding of the city Canadians love to hate: the city of Toronto.

The place was well known to the Huron, Iroquois, Missisauga and other First nations who tramped the portage along the Humber River to Lake Simcoe en route to Georgian Bay. Certainty about the meaning of Toronto is lost but it likely originated as the Mohawk phrase tkaronto, meaning "where there are trees standing in the water."

French explorer and adventurer Etienne Brulé was the first European to travel the passage de Toronto in September 1615. The French built their third and last post there, Fort Rouillé, in 1751. In retreat during that final war with the English, the French put the torch to it in 1759.

Both the Iroquois and the French built and abandoned posts there before the British purchased the area from the Missisauga for £1700 in cash and goods, arguably as good a deal as the one the Dutch made for Manhattan. On August 26 1793, Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe arrived. He named the place York in honour of the Duke of York's recent victory in Holland and made it the temporary capital of Upper Canada, giving it a decided advantage over its more attractive rivals Kingston and London.

Through that hard winter, Simcoe kept his Queen's Rangers busy clearing a town site and cutting roads: Yonge Street (named for the secretary of war) running north, Dundas (for the home secretary) west, and Danforth (for the contractor) east.

The village got its first jail in 1799, first newspaper, the Upper Canada Gazette, in 1798 and its first church, St. James, in 1806.

|

| York, by Elizabeth Hale (NAC C40137) |

In the late 1820s a sudden flood of immigrants created a growing colonial town, riven with deep ethnic, class and religious fissures: Scots, English and Irish (Protestant and Catholic) were divided by ethnic, class and religious differences. To be on top, in the political elite, it helped to be English but was mandatory to be Church of England.

This ethnic and religious brew, vying for political power, was one that could not be found in Britain itself. It was a society in which historian Paul Romney described "everyone was conscious of belonging to a minority." The chief agitator was the Scottish firebrand William Lyon Mackenzie who relentlessly poured scorn on the ruling elite. In retaliation, Tory supporters beat him up and wrecked his printing shop. At least he was spared the fate of journalist Francis Collins, who was imprisoned, and Reformer George Rolf, who was tarred and feathered.

While the number and diversity of the newspapers stoking the political furnace might seem alien to us today, we would recognize the sleazy squib The Porcupine, which pandered to rumour and gossip and denounced some as homosexuals, adulterers, or philanderers and others for stupidity or the size of their nose.

The ruling conservatives had opposed incorporation because it would bring elected institutions, which they rightly feared would be open to rabble and reformers. When Mackenzie was elected Toronto's first mayor on April 3, their worst nightmare came true.

As mayor Mackenzie's responsibilities included holding a daily police court and meting out punishment for crimes such as drunkenness, wife beating, breaking the Sabbath and bootlegging. He applied himself diligently and was vilified in the press by one faction or other for each decision.

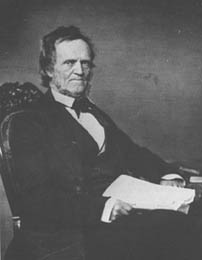

|

| William Lyon Mackenzie (Metropolitan Toronto Library) |

When Mackenzie published a letter in his paper suggesting that Upper Canada would be better off as a republic, it provoked a firestorm. He called a public meeting to explain himself and spoke so long that his opponents had no time to respond. The meeting was reconvened the next night but tragedy struck when the packed gallery in the St Lawrence Hall collapsed and four people were fatally gored by butchers' hooks as they fell.

A worse catastrophe befell the city that first year when cholera stalked the polluted streets, killing perhaps 500 people.

The city council's first term ended with a predictably tumultuous election. Since each citizen declared their vote in public, they, and the candidates, were exposed to all kinds of intimidation. Since most of the Irish could not vote, they energetically participated by cracking skulls. When a robust group of brawling Irish Catholics engaged a group of Protestant Orangemen, the result was a riot and the death of one man, Patrick Burns.

Even the death of Burns caused Mackenzie grief when an investigation incriminated his chief of police William Higgins (a jury exonerated him).

The election of January 1835 ended Mackenzie's brief reign, perhaps to his own relief. So far in its history Toronto was living up to its name as a "meeting place." In that first year we first see the growing pains of a new society and the beginnings of the struggle to find the political accommodations that could tame the cultural diversity that is still the hallmark of Canada and above all of its largest city.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom