Created in Upper Canada, where enslavement had been limited in 1793, the corps was composed of free and enslaved Black men. Many were veterans of the American Revolution, in which they fought for the British (see Black Loyalists). The Coloured Corps fought in the Battle of Queenston Heights and the Battle of Fort George before it was attached to the Royal Engineers as a construction company. The unit was reactivated during the Rebellions of 1837–38 (and also served as a police force during the construction of the Welland Canal).

Black People in Early Upper Canada

The first substantial settlement of Black Canadians in British North America occurred following the American Revolution. Some, such as Richard Pierpoint, a formerly enslaved man from Bondu (Senegal) and military veteran of the revolution, had gained their freedom by fighting under the British Crown during the war. Most, however, were enslaved and therefore brought to the British territories as spoils of war or as the property of Loyalists.

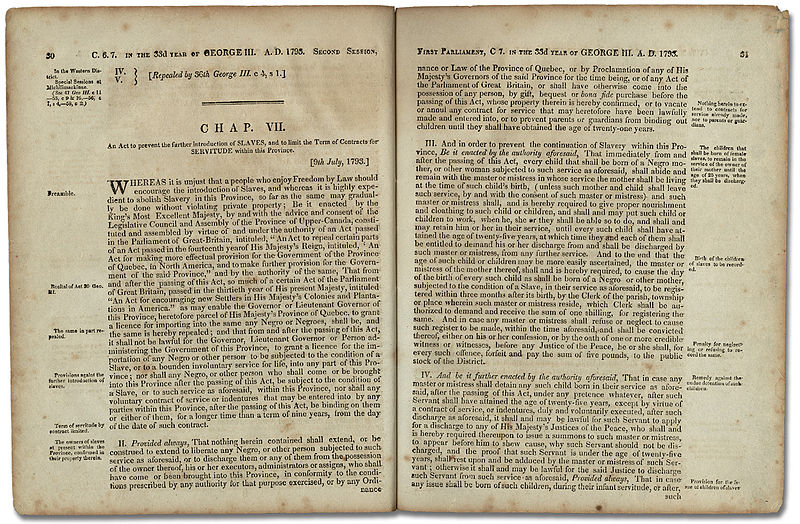

About 500 to 700 Black people lived in Upper Canada (Ontario) by the time Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe arrived there in 1792. Simcoe wished to abolish enslavement entirely, but the Upper Canada legislature opposed many of his reforms. Many of the members of both houses of the legislature either enslaved Black people or were from slaveholding families and were therefore concerned over the possible economic impact abolition would bring (see Black Enslavement). Therefore, the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, passed on 9 July 1793, was a severely limited version of Simcoe’s intentions. It banned the further importation of slaves into Upper Canada and limited terms of enslavement to nine years. As the Harriet Tubman Institute for Research on Africa and its Diasporas at York University points out, it is difficult to know which soldiers in the Coloured Corps were free and which were enslaved.

Raising the Coloured Corps

Toward 1812, the prospect of an American invasion posed a major threat to the liberties enjoyed by some Black Canadians, leading many Black men to join the militia. Many understood that American victory could lead to re-enslavement. Free Black men had served in the militia since its organization in 1793. However, the formation of an independent company composed entirely of Black men was not proposed until the eve of the War of 1812, when Richard Pierpoint offered to raise a corps of Black men in the Niagara region. The offer was initially rejected by the Upper Canada government, but reconsidered following the American occupation of Sandwich (Windsor) on 12 July 1812.

By late August, the core of an all-Black Canadian company had formed in Niagara, as part of the 1st Lincoln Militia. But instead of granting Richard Pierpoint command, the honour was bestowed to a local White officer, Captain Robert Runchey. Characterized as a “worthless, troublesome malcontent” by his superiors, Runchey fulfilled his reputation for poor leadership by segregating Black men from other militiamen. In some cases, Runchey hired out Black soldiers as domestic servants to other officers.

Not surprisingly, recruiting in the Niagara Peninsula proved difficult, and “Runchey's Company of Coloured Men” remained small. In early October, 14 Black soldiers were transferred to the unit from the 3rd York Militia.The majority of men in the corps lived in Upper Canada — in towns and villages in the Niagara region, in York (Toronto) and the Bay of Quinte, near Belleville (see Quinte West). One of the men, George Martin, from Niagara, had been freed from enslavement by his father, Peter, in 1797.(Four years before that, Peter Martin witnessed and reported the Chloe Cooley incident to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe — an event that led to the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.)

Once raised to approximately 40 men, the company commenced training at Fort George.

Battle of Queenston Heights

On the morning of 13 October 1812, American forces under Major General Stephen Van Rensselaer III invaded Upper Canada by crossing the Niagara River at Queenston. Runchey's Company marched to Queenston from Fort George with Major General Roger Sheaffe's reinforcements, arriving after Sir Isaac Brock's death that same day. The company joined Captain John Norton's Six Nations warriors in sniping at the American position from atop Queenston Heights, before forming part of Sheaffe's battle line.

Alongside the 41st Regiment of Foot and the 49th Foot, Runchey's Company “fired a single volley with considerable execution, and then charged with a tremendous tumult,” bringing about the Americans' surrender. Having absented himself on the morning of the battle, Runchey subsequently resigned, and the company was commanded temporarily by Lieutenant James Cooper of the 2nd Lincoln Militia. Cooper was cited in dispatches as having led his men “with great spirit.” (See also Battle of Queenston Heights.)

1813 Campaigns

Renamed the “Coloured” or “Black” Corps, the company entered general service and spent the winter at Fort George. On 27 May 1813, a large American force launched an amphibious attack against the fort (see Battle of Fort George). The Coloured Corps and British troops rushed to the beach to oppose the landing and “exchanged a destructive and rapid fire” with the enemy at short range. The Coloured Corps lost four of its men wounded or captured before it was forced back by naval gunfire. It retreated with Brigadier General John Vincent’s troops to Burlington Heights. For the remainder of the year, the Coloured Corps participated in the blockade of the American army at Fort George, enduring the same harsh conditions and privations as British troops.

Construction of Fort Mississauga

After the British captured Fort Niagara on 19 December 1813, the Coloured Corps was attached to the Royal Engineers to help repair fortifications at the mouth of the Niagara River. Whether racism influenced the authorities’ choice for this duty is not known, as one engineer later reported: “When I visited the Niagara Frontier… I found that a corps of Free Men of Colour had been raised… but had been turned over to that of the Engineers, any necessity for this I never could learn, but it seems to have been the fashion in Canada to heap all kinds of duties upon the latter.”

Toward the spring of 1814, the company was ordered to construct a new fort on the Canadian shore, dubbed Fort Mississauga. With the American navy in control of Lake Ontario, this work was crucial to the security of British forces in the Niagara Peninsula. One British officer later noted that “Mississauga… is a pretty little Fort, and would prevent vessels coming up the river.” These duties consequently prevented the Coloured Corps’ participation in the Niagara campaign that summer, even during the subsequent siege of Fort Erie, in which British forces desperately lacked trained engineer troops.

Disbandment and Legacy

The Royal Engineers continued to employ the Coloured Corps in the Niagara Peninsula for the remainder of the War of 1812. The corps’ zeal in these works duly impressed British engineers, one reporting in February 1815 that “no people could be better calculated to build temporary barracks than these Free Men of Colour, as they are in general expert axemen.”

The company was disbanded on 24 March 1815, following the end of the war. In claiming rewards for their service, many faced adversity and discrimination. Sergeant William Thompson was informed he “must go and look for his pay himself,” while Richard Pierpoint, then in his 70s, was denied his request for passage home to Africa in lieu of a land grant. When grants were distributed in 1821, veterans of the Coloured Corps received only 100 acres, half that of their White counterparts. Many veterans did not settle the land they were granted because it was of poor quality. Despite these inequities, the Coloured Corps defended Canada honourably, setting the precedent for the formation of Black units in future.

A Coloured Corps was again raised in Niagara during the Rebellions of 1837–38, one of several Black or “Coloured” corps that volunteered for service — other units were raised in Toronto, Hamilton, Chatham, and Sandwich (Windsor).

Black Canadians in the British Service

In addition to serving in militia units, other Black Canadians enlisted in the regular British forces and served in Upper Canada. One of their most common roles was as percussionists in military bands. An officer of the 104th Foot recalled the regiment's bass drummer, Private Henry Grant, accompanying his regiment's epic winter march through the snow from New Brunswick to Upper Canada between February and April 1813. After reaching Kingston, he and the band took part in the Battle of Sackets Harbor on 29 May 1813, in which several band members were killed.

Other British regiments garrisoned in Canada for long periods recruited Black Canadian musicians in a similar manner, including the 100th Foot, whose cymbal player was Black.

Some British regiments permitted individual Black Canadians to enlist as combatant soldiers during the War of 1812. Several men are known to have served in the ranks of the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles: an unnamed Black man was noted by an American officer as having been killed in action during the defence of Fort George in May 1813 (see Fencibles in the War of 1812). More unusually, the entire pioneer squad (the equivalent of modern combat engineers) of the 104th Foot was comprised of Black Canadians. One of those men, Private John Baker, was wounded at Sackets Harbor and recovered to fight in the battles of Chippawa and Lundy’s Lane during the summer of 1814.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom