No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) — also known as the Black Battalion — was a segregated non-combatant unit during the First World War. It was the largest Black unit in Canadian military history. This is their story.

Checkerboard Army

In 1916, thousands of Canadians lay dead in Europe’s Great War. In Canada, thousands more signed up to help out their brothers and sisters. But one group of men was turned away almost every time. They were fit to fight — but the Canadian Army rejected them.

Lindsay Ruck: There were a few different things they heard. Everything was based on the colour of their skin. So they were told that “We don’t want a checkerboard army.” They were told that, “This is a White man’s war.” They were told they weren’t fit to fight. And it’s all because they were Black. So despite the fact that they were there and eager, and willing, they were still told that they weren’t good enough, essentially, to fight alongside White soldiers.

That’s Halifax writer Lindsay Ruck. She recently updated her grandfather Calvin Ruck’s book, Canada’s Black Battalion. It tells the story of what those men did next.

She says it was all very Canadian — no official discrimination. Every able man was free to enlist — and every officer was free to reject them. And somehow, all across a Canada increasingly desperate for soldiers, pretty much every Black man was rejected. Lindsay Ruck says the insult soured some volunteers. But others fought to fight.

Lindsay Ruck: I know that I don’t take rejection very well in any instance, so the fact that these men were told that “No, we don’t want you, you’re not good enough,” but there were still hundreds who said we want to represent our country, and I think for them it was a thing of pride.

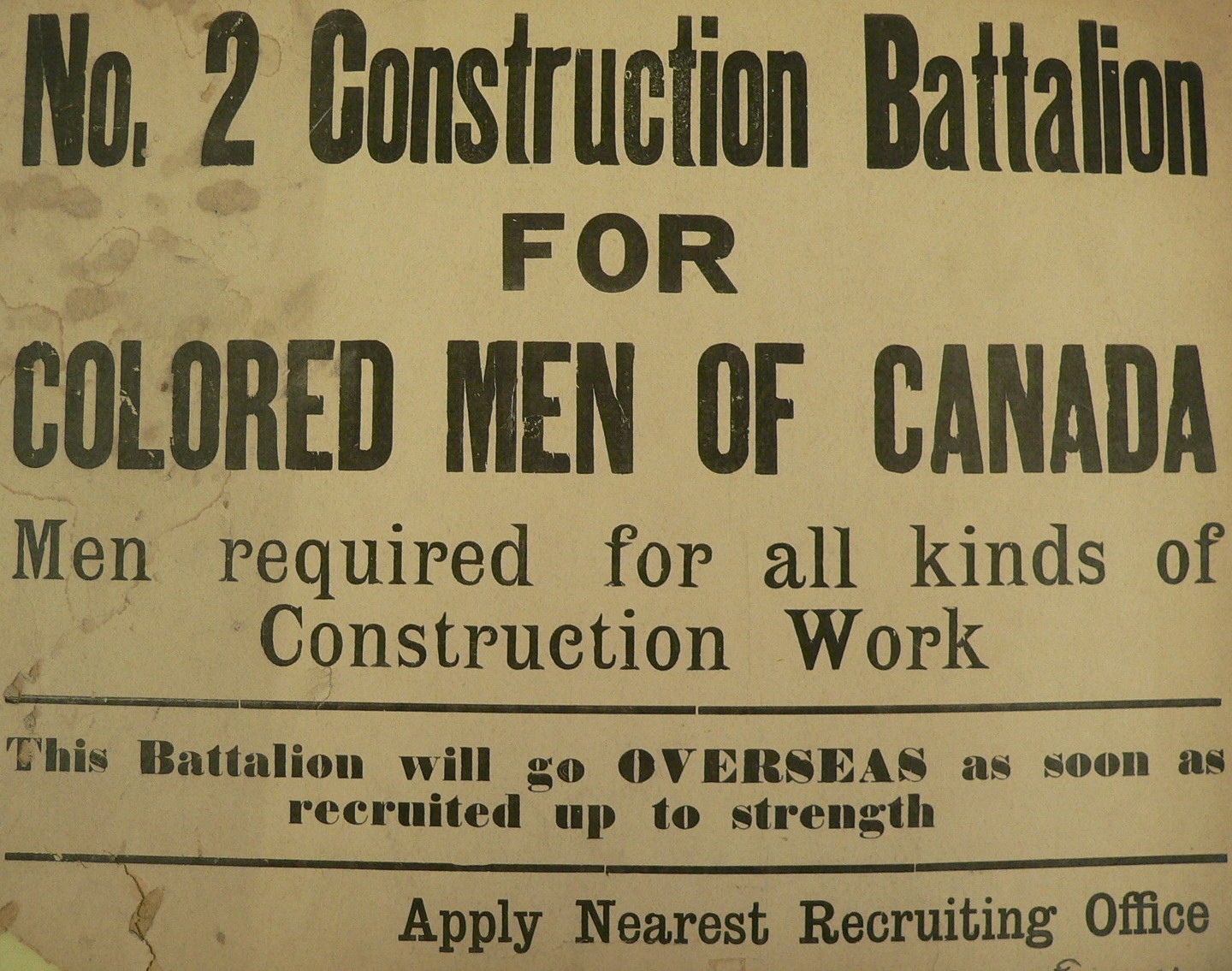

Hundreds of Black men from across Canada signed up. Leading figures in Black communities in Nova Scotia and Ontario engaged in a letter-writing campaign. Their request for an all-Black battalion made it to Sir Sam Hughes, the head of Canada’s forces in the war. The issue of anti-Black discrimination was even raised in the House of Commons.

On 11 May 1916, the British War Office in London said it was willing to accept a segregated unit. Less than two months later, the No. 2 Construction Battalion was formally authorized on 5 July 1916. The segregated non-combat unit was the first — and only — all-Black battalion in Canadian history.

Lindsay Ruck: They were doing it for a greater cause. I think that pride was a big thing.

They formed in Pictou, but soon moved headquarters to Truro. It was thought that being close to Truro’s Black community would stimulate recruitment.

When some of the men tried to relax by going to the cinema, they were told they could only sit in the segregated balcony. After heated protests from the men and from their officers, the cinema quietly desegregated. It was a first, small victory for the men of the No. 2.

In December 1916, word came from Ottawa that the battalion was needed. On 28 March 1917, they sailed for Europe. They were 19 officers — mostly White men — and 605 Black recruits.

The war was almost three years old, and no end could be seen. The battalion got to work, many of them with the Canadian Forestry Corps. After 18 months, the war ended, and the men came home in 1919.

Lindsay Ruck: I think that’s why a lot of them chose not to tell their story and why it took so long to get the story out there, because they didn’t return as heroes. They went back to being a second-class citizen, a Black man, and had to deal with the segregation that they dealt with overseas. So, nothing really changed for them, despite the fact they went over there and risked their lives.

Lest We Forget

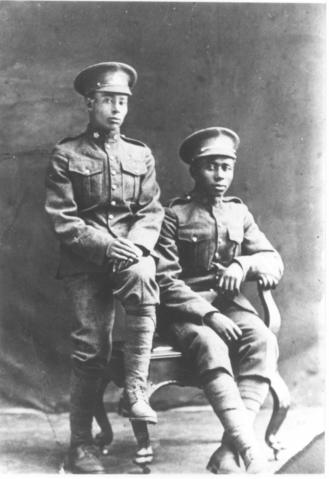

George Downey came home to start a family, which soon included his son Dave. Looking at a photo of his father in uniform, Dave says he knew little about the Black Battalion or his dad’s role in it — only that his dad made him keep that uniform looking sharp.

Dave Downey: Well, when I was a kid, like, you see anything brass on there, he had us doing it, and polishing his shoes. I remember I knew nothing about no spit shines, and he was telling me, he was showing me, and then we used to have to do it.

We’re sitting at a kitchen table in his north-end Halifax home. The walls are filled with reminders of Dave Downey’s own legacy. Apart from a four month stretch in 1970, Dave was the middleweight boxing champion of Canada from 1967 to 1975. When one of his 20 grandchildren visits, he makes sure they see his championship belt before they eat the sweets. He wants them to know what they can do. Perhaps that comes from his father saying so little about his own achievements.

Dave Downey: Then I seen, like I said, all these men coming here into my home, and it was kind of ironic. You’d sit there and my mom would say, “Don’t you fellows go in the living room. Your dad’s in there talking to people about things that happened in the war — it don’t concern you. You fellows go out and do something — go outside and play.”

But whenever any of these gentlemen come from Truro or anywhere — these people, you know, they’re like a god. They’re sitting there talking to my father, and you can’t be in that room.

One of those men was Calvin Ruck — Lindsay Ruck’s grandfather.

Dave Downey: Mr. Calvin Ruck came to my house all the time. He was always in my father’s house, picking his brain and Mom said, “They’re in there talking about the war. You don’t want to know about that, it wasn’t pleasant.” And she said, “When you get old enough, if you want to join the service or something like that, then he’ll probably talk to you about it.” But he never did.

Things, sometimes, never get said about what my father did in [the First World War]. I don’t think he’s the head one or anything like that. He was just a plain, ah… novice or a regular army guy. But to be there and be doing things, I guess, was really astonishing for him. I said probably, where he comes from over in North Preston, it’s an honour.

Sylvia Parris says her father, Joseph, had similar motivations. He was one of the very first people to join the battalion.

Sylvia Parris: You know, it’s really been neat to have the opportunity to think about Daddy’s experience. He was 17 when he left Mulgrave and made that big trek to New Glasgow to enlist. His brother, my uncle Bill, left a few weeks after to go to his enlistment in Truro.

I think it was adventure — a young man who’d be wearing this uniform — and as we see in the pictures, he just looked so strapping and handsome in that uniform. So there would probably be that aspect of [adventure]. But I would think too there was a kind of an economics to it.

Enlisting provided funds to help his parents keep the family farm operating. It was a job for him in a country not eager to employ Black men.

Sylvia Parris: I really swell up with pride when think about that whole idea of going off to fight for a country, which you would have understood did not value you as a human being. There’s this thing about Black community being together. For folks to know that there was this battalion — even though the reason for it was about a thing that society was denying people, as I said, their humanity and value about where they are in terms of contributions and ability to contribute — there’s this thing about community coming together. So you had Black geographic community, you had cultural community and they’re all going together to this place and they’re going to be together in this work. I think that that would have been very exciting for my father as well.

She remembers her father as a giant, his stature as a leader was apparent even then, at 17 and going off to war. His Catholic faith provided inspiration and comfort.

Sylvia Parris: I can see him even at his young age being kind of the leader that would provide encouragement to anybody where their heart was feeling less strong when they got engaged in that war. He would be the practical one in terms of helping people, helping the men — helping his brothers — to be strong, to do things in terms of their survival. I can just see him taking leadership in that.

Sylvia is the second-youngest of Joseph’s 15 children. He died while she was in junior high school, and she knew only dimly of his service.

Sylvia Parris: It wasn’t talked about in the house and we hadn’t learned about it in school, so there wasn’t a way to kind of bring it up. How nice it would have been to have been in the classroom and been learning about the battalion, and then be asked by my teacher to go home and ask your family about it, right? That would have opened up the story for us. But it didn’t happen that way. So we now are just learning ourselves.

Remembrance

The story of the No. 2 Construction Battalion nearly fell out of the history books altogether. But then Calvin Ruck got to work.

Lindsay Ruck: Someone needed to tell the story, and he took it upon himself to do it.

He wrote Canada’s Black Battalion based on all those talks with the men — like the long conversations Dave Downey eavesdropped on when he was a boy. Ruck talked to Joseph Parris too. Both men worked on the trains after the Second World War. It was one of the few good jobs available to Black men — a further reminder that they were second-class citizens, war or no war.

Ruck’s work led to an emotional reunion of the Black Battalion in November 1982, when three hundred friends and family of the aging soldiers held a celebration at the Lord Nelson Hotel in Halifax. The nine surviving veterans of Canada’s Black Battalion marched smartly into the ballroom to a war-time favourite, “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.” The crowd cheered them.

All the men are gone now. But people still gather to honour them. Lindsay Ruck’s been going to such celebrations since she was a girl.

Lindsay Ruck: And at that time, I knew very little about the battalion. I just knew that my grandfather had written a book about the battalion and he had started these commemoration ceremonies in Pictou to honour these men.

I felt that after my grandfather had passed away — and the fact that these commemoration ceremonies were still going on — I wanted to continue on with that legacy as he did and just do my part in any way that I could.

She’s updated his book so a new generation of Canadians will know about the No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Lindsay Ruck: People who maybe knew nothing about the battalion are now taking an interest and are realizing that — just like my grandfather — even though they didn’t go to war, they have this connection, because they may know what it felt like to not be wanted.

For Ruck, the battalion’s legacy is how it can inspire people to fight through discrimination.

Lindsay Ruck: That’s because of pioneers like the Black Battalion, who said we want to do it and we’re going to do it, despite what everyone else is saying. So the legacy is huge, and I think it’s pretty special. It’s an important story that needs to continue to be told. I’m glad that conversations like we’re having now are happening, because this is part of our history.

On 9 July 2016, people will gather again in Pictou to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the battalion’s formation. Dave Downey will be there to honour his father, George.

Dave Downey: It’s an honour. All I can do is pay my respects for him by going down there to see. I just wonder if he would have wanted to go down there. One of us would have drove him down or something. I know he would love it. I don’t know if he would want to talk about it, ’cause he’s that type of man.… He didn’t talk too much to people.

Sylvia Parris will be there too, for her father, Joseph.

Sylvia Parris:He’d be so humble. He would be convinced to accept being there, but he would not be the person who would step out and ask to be there. It certainly means a lot in terms of personal family pride. It means a lot too that now … the timing seemed to have been right in terms of the recognition of the battalion and inviting other folks to look into their photos and to start their kitchen conversations about their family members being in it — so their fathers, their grandfathers, their uncles, right?

The other thing that I think is really important about this is that it’s an opportunity for young folks to be re-energized with pride and community and to see how doing the right thing, doing what is about justice, is important to recognize. While we still are challenged with systemic issues, we are encouraged by looking back to that past to hold to truth and to hold to justice.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom