Tookoolito, also known as Hannah and Taqulittuq (born in 1838 near Cumberland Sound, NU; died 31 December 1876 in Groton, Connecticut), Inuk translator and guide to American explorer Charles Francis Hall. Tookoolito and her husband, Ebierbing (traditionally spelt Ipiirvik), were well-known Inuit explorers of the 19th century who significantly contributed to non-Inuit’s knowledge of the North. The Government of Canada has recognized Tookoolito and Ebierbing as National Historic Persons.

Early Life

Born near Cumberland Sound in present-day Nunavut, Tookoolito became known for her talents during the mid-1800s as an Inuk interpreter and advisor to whalers and explorers. Her brother, Eenoolooapik, also gained popularity as an Inuk guide.

Wed as teenagers, Tookoolito and her husband, Ebierbing (also known as Joe, born circa 1837 on an island in Cumberland Sound, NU; died circa 1881 in the Arctic), travelled together until shortly before Tookoolito’s death in 1876.

Travels with Thomas Bowlby

Tookoolito and Ebierbing first worked as guides for Englishman Thomas Bowlby. In 1853, Bowlby took the couple with him back to England. Like many Indigenous peoples of the time, the couple were put on display in various exhibits as “exotic” peoples of the New World. Tookoolito and her husband caused quite the sensation among locals, and even attracted the attention of Queen Victoria, who received them at Windsor Castle.

Tookoolito learned to speak English fluently while in England. While Tookoolito adopted English customs and ways of life — such as drinking tea and wearing English clothing — she still maintained her Inuit culture. After approximately two years in Bowlby’s service, Captain William Penny returned Tookoolito and Ebierbing to Baffin Island.

DID YOU KNOW?

Belgian pianist Auguste Dupont composed the “Tickalicktoo Polka” to honour Tookoolito and Ebierbing’s visit to Windsor Castle. The only surviving copy of the sheet music rests in The British Library in London.

Work with Charles Francis Hall

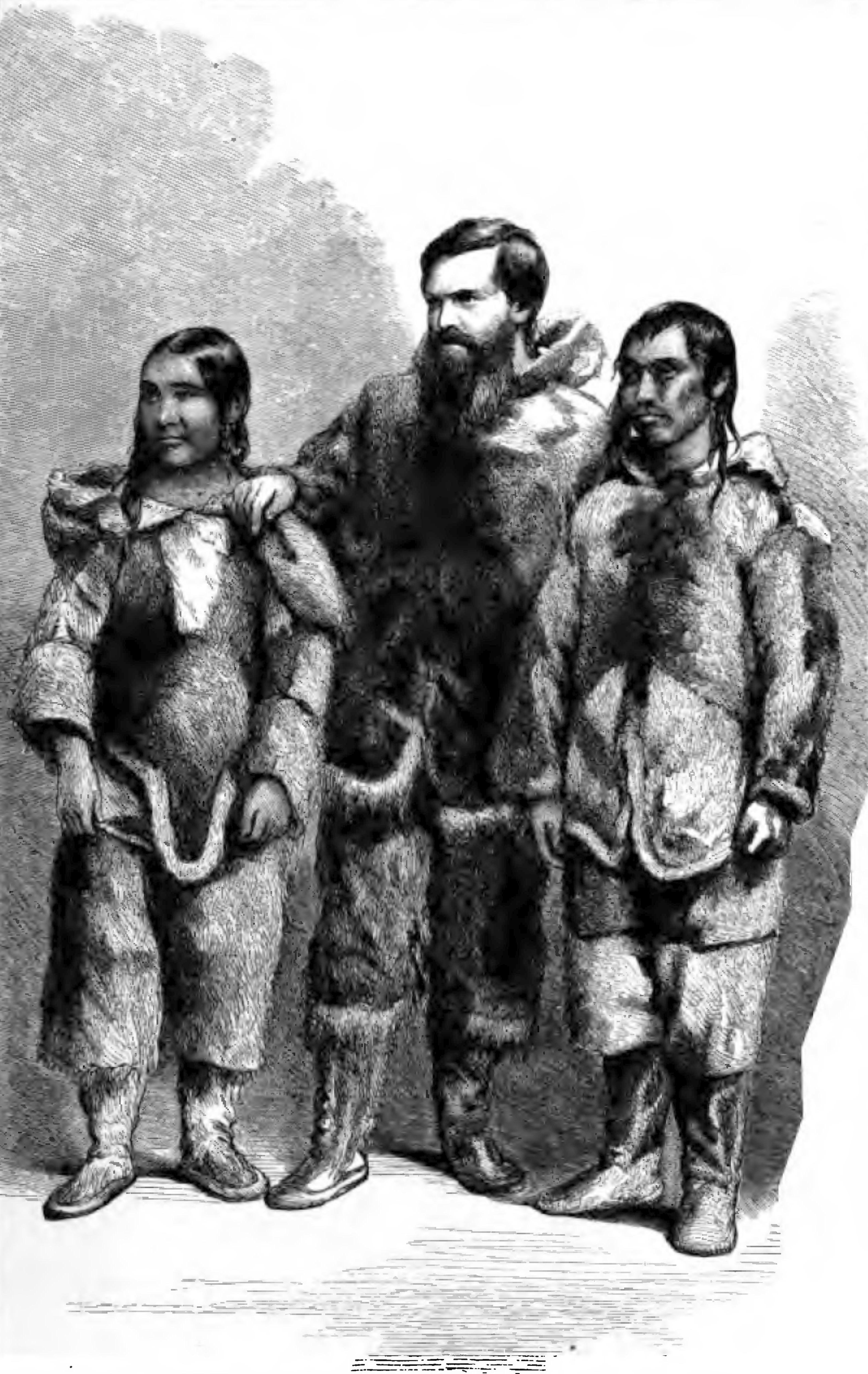

In the fall of 1860, Tookoolito met American explorer Charles Francis Hall. He was looking for Inuk guides to help him locate the remains of Sir John Franklin. Impressed with the pair, he saw Tookoolito and Ebierbing as promising travelling companions. For over 10 years, the three of them conducted three expeditions together.

During Hall’s first expedition (1860–62), Tookoolito and Ebierbing guided Hall through Frobisher Bay. Towards the end of the expedition, Tookoolito gave birth to her first child (a boy).

The couple then accompanied Hall back to the United States, where they were exhibited at Barnum’s American Museum, Boston’s Aquarial Gardens and at Hall’s lectures to generate funding for the next expedition. Sometime during these appearances, Tookoolito and her child became ill. In the spring of 1863, the child died. The death has been attributed to the frequent exhibition of the family. Tarralikitaq was buried in Groton, Connecticut, a place that became a home away from home for Tookoolito and Ebierbing.

On Hall’s second expedition (1864–69), he, Tookoolito, Ebierbing and other explorers travelled to Naujaat (Repulse Bay), searching for clues to the fate of Sir John Franklin and his lost expedition. (See also Franklin Search.) The expedition was ultimately a failure; Hall only found some skeletal remains and objects once belonging to the Franklin crew.

Sometime during their travels, Tookoolito had a second son, known only as King William (presumably after King William Island — the destination of the expedition). The infant died during the expedition. Sometime after, Tookoolito and Ebierbing adopted a daughter. They returned to the United States with Hall after the expedition and lived in a home in Groton.

After a couple of years living in the United States, Tookoolito and Ebierbing joined Hall on what would be his last Arctic expedition (1871–72). Known as the Polaris expedition (named after the ship they were on), Hall attempted to reach the North Pole. Hall died not long after, allegedly poisoned by a member of the expedition.

The expedition continued, though their morale had now deteriorated. During an ice storm in 1872 or 1873, the captain of the Polaris, Sidney Buddington, ordered the abandonment of the ship, which was anchored to an ice floe in Smith Sound. Many of the ship’s crew, including Ebierbing, Tookoolito and their daughter were left marooned for six months. The castaways drifted about 2,000 km south and, having survived the ordeal thanks to the hunting skill of Ebierbing and another Inuk, were eventually rescued off Labrador by a sealer. The health of Tookoolito’s daughter was compromised during this time; she died in 1875.

DID YOU KNOW?

Some geographic locations have been named in honour of Tookoolito and her family, including Ebierbing Bay and Tookoolito Inlet (near Cornelius Grinnell Bay). Butterfly Bay (Tukeliketa Bay) is found south of Tookoolito Inlet. Ebierbing’s grandmother, who assisted Hall in his first expedition, had an island named after her — Ookijoxy Ninoo Island (now Shepard Island).

Death

Only 38 years old, Tookoolito died in 1876 at her home in Groton. She was laid to rest in the Starr Burying Ground, in Connecticut, along with her children.

After Tookoolito’s death, Ebierbing accompanied the American Eothen expedition in 1878 to find the Northwest Passage. Ebierbing remained in the Arctic afterwards and died sometime thereafter, possibly around 1881. Although Ebierbing never went back to Groton, his name is inscribed on Tookoolito’s grave marker there.

Significance

Tookoolito was an adventurous and intelligent woman who, along with Ebierbing, contributed significantly to various Arctic explorations. Tookoolito helped Hall and others to survive in the Arctic, to communicate with the Inuit and to learn more about Canada’s North. A mentor, teacher, friend, wife and mother, Tookoolito was an incredible person, who accomplished much in her short life.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)