Background

The years leading up to the raids were tense for Toronto’s gay community. Egg- and insult-tossing at drag performers heading to Halloween balls along Yonge Street grew to the point where municipal and police intervention was required to control the public. The August 1977 sexual assault and murder of shoeshine boy Emanuel Jaques by several men in a Yonge Street massage parlour provoked sensational media coverage that emphasized the participation of gay men. Shortly after Jaques was murdered, an article by Gerald Hannon in the gay liberation journal Body Politic, “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” added to public intolerance of gay men and resulted in a police raid of the publication’s office.

At the same time, community relations with the Metropolitan Toronto Police Force deteriorated. Bathhouse owners whose businesses were once tacitly approved by the morality squad were no longer informed of upcoming police actions, resulting in a series of small raids beginning in December 1978.

In the March 1979 edition of the Metropolitan Toronto Police Association newsletter, staff sergeant Tom Moclair’s essay “The Homosexual Fad” portrayed gay men as arrogant, militant deviants who recruited innocent children into their lifestyle. This moralistic view was found among many officers by law student and journalist Arnold Bruner while compiling a study for the city on police relations with the gay community following the raids. Bruner summed up those views as “stereotyped notions of the homosexual man as an uncontrollable sexual libertine who commits crimes of lust, prostitutes himself, who is capable of infecting those with whom he comes in contact with by spreading homosexuality or venereal disease.”

Police also targeted public washrooms known for clandestine encounters, sometimes hiding in the vents to catch sexual acts.

Operation Soap

During the Operation Soap raids, police entered the four bathhouses at 11 p.m. and used crowbars to open patron lockers. Undercover police wore red dots on their clothing to show, according to one officer, “who are the straights.” Accounts from those arrested later presented to city council described hateful police behaviour. One officer allegedly told a line of men standing against a shower wall “I wish these pipes were hooked up to gas so I could annihilate you all,” a reference to Nazi death camps (see Canada and the Holocaust). Police compiled large amounts of personal information about the men rounded up, including the names of their work superiors and, for those who were married, names and phone numbers of their wives. The arrested feared retaliation from the police, who were known in the past to have made “concerned citizen” calls to employers when charges revolving around sexual orientation were laid.

When the night was over, 286 men were charged for being found in a common bawdy house (a brothel), while 20 were charged for operating a bawdy house. It was, up to that time, the largest single arrest in Toronto’s history. The bathhouses suffered $50,000 in damaged items. No incidents of sex work were uncovered.

Community Response and Action

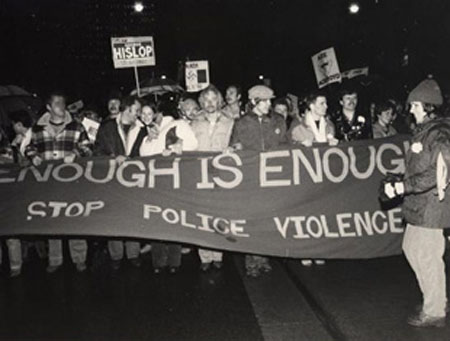

The following evening, a midnight march protesting police brutality began at Yonge and Wellesley streets. Peaking at over 3,000 participants, the procession headed south to 52 Division police station on Dundas Street. As protestors chanted messages such as “gay rights count,” a small group of mostly teenaged counter-protestors yelled back homophobic obscenities and unsuccessfully attempted to block University Avenue.

At the police station, the protest encountered a human barricade of about 200 officers. The protest headed north to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Violence between police and protestors broke out, causing organizers to urge the crowd to disperse. While most did, a group of about 400 headed back to Yonge Street, where, following a further reduction in numbers, they faced insults and more violence. The protest resulted in 11 arrests, one injured police officer, one damaged police car and four smashed windows in a streetcar. Body Politic columnist Ken Popert later wrote:

“I know that something got into people, because it got into me.… What got into me was my own anger over living in a society which finds my existence inconvenient. What got into me was my own anger over harassment on streets that are never safe for me. What got into me was my own anger over the unrelenting stream of taunts and insults from the media, coolly calculated to undermine my self-respect with every passing day.... As long as society continues to demand us as its victims and its human sacrifices, that anger is going to be there, waiting to get into us, again and again. It’s not going to go away for a long, long time.”

Public Reaction

Though police officials claimed that the raids were merely a bust that wasn’t intended to intimidate the gay community, public outcry against police brutality and the violation of civil liberties grew over the following days. CHUM radio news director Dick Smyth criticized police for “ham-handed brutality and lunk-headed vandalism,” and called them “pigs” (a slur against police) on air. An editorial published in the Globe and Mail on 9 February pointed out the hypocrisy of the raids, and their implications for a wider range of communities in the city:

“There have been no such raids on other private clubs in Metro Toronto. There have been no such raids on heterosexual bawdy houses in Metro Toronto. Even in the days when there were raids on heterosexual bawdy houses, few charges were laid against found-ins. The impression upon the public cannot fail to be that the police are discriminating against homosexuals, knowing that the relatively minor charges which have been laid against so many people may give them major problems in their private lives — hurting them in their jobs and families, exposing them to the abuse of those who would deny homosexuals any rights.”

The Toronto Sun attacked that editorial two days later, accusing its competitor of “spouting editorial nonsense that homosexuals are being picked on.” In an interview with the CBC, Sun editor-in-chief Peter Worthington stated that “there’s a certain flaunting at the moment in the homosexual community,” and that he believed “a person’s sexual orientation or preferences should remain in the closet.” When asked about his threat to reveal the names of found-ins after future raids — which other papers, including the Toronto Star, had done in the past — Worthington felt that such a tactic would deter anyone contemplating visiting a bathhouse.

Legacy and Significance

Over time, the bathhouse raids came to be considered as Toronto’s equivalent of the 1969 Stonewall riots, in which patrons of a New York City gay bar called the Stonewall Inn fought back against police harassment. Most of those arrested in Toronto were found innocent of the charges laid against them. Though a full inquiry into the raids never materialized, municipal studies prepared in their aftermath helped to slowly improve the relationship between police and the gay community, though strains continued into the 21st century. Subsequent raids of Toronto bathhouses, gay and lesbian strip clubs and nightclubs continued, with raids in June 1981, April 1983, February 1996 and September 2000. The growing politicization and support of the gay community fueled civil rights activism, made homophobia less acceptable, and have led to Pride becoming one of Toronto’s largest annual public celebrations (see LGBTQ2S Rights in Canada).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom