For much of Toronto’s early history, the dominant cultural force in the predominantly Protestant enclave was church music. By the beginning of the 20th century, Toronto was known as “the choral capital of North America.” By that time, the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra were well established. The city has also been an epicentre of piano building, music publishing, and the English-language recording and broadcasting industries. In addition to classical and choral music, Toronto has been a national centre for jazz artists, folk musicians, rock ‘n’ roll bands and R&B and hip hop artists. The city is home to the headquarters of many major record labels and cultural institutions, as well as some of the country’s oldest and best-known concert halls.

Historical Background

Toronto, on the north shore of Lake Ontario, was founded as York by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe in 1793. It was the capital of Upper Canada from 1796 to 1841, of the Province of Canada 1849–51 and 1855–59. It was designated the capital of Ontario in 1867, the year of Canada's Confederation.

The settlement's population, less than 200 in 1799, consisted originally of civil service and garrison personnel. In 1834, with a population of 9,252, York was incorporated as the city of Toronto. Before the First World War, most Torontonians were of English, Irish and Scottish extraction. But successive waves of emigration from many parts of the world, beginning early in the 20th century, significantly altered the city's ethnic makeup. In 1953, 13 area municipalities amalgamated to form the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto. By 1986, it had a population of more than 3.4 million.

Because of Toronto's early designation as the capital of Ontario, it became a major centre of administration, commerce, education and industry. As the most populous city in English Canada, as well as its media capital, it became the national headquarters for many cultural organizations. Toronto was home to the largest number of book and music publishers and the richest libraries in Canada. It equalled and eventually surpassed Montreal as a broadcast production centre and employer of professional artists.

1793–1918

The progress of music in the Toronto of the 19th and early 20th centuries was linked with the city's burgeoning population and prosperity. From a few hundred souls, population grew to more than 500,000 by 1920. In the 1830s and 1840s, performing groups were established and auditoriums were erected. Later in the century, education, publishing and piano building began to thrive, and many touring artists and ensembles of world fame visited Toronto to perform.

On 30 July 1793, when the schooner Mississauga took Simcoe to Toronto for the first time, the Queen's Rangers band was on board ship. But the first extant reference to a musical event in Toronto is an itemized account including “7 Dollars Paid musick by Order” for a ball and supper on 4 June 1798, to celebrate the king's birthday. In 1810, Joseph B. Abbot proposed to open “a School in the principles of Church Music.” That same year, the performance of a company of actors from Montreal featured a group of songs between a play and a farce. In 1811, a “double Key'd Harpsichord and Piano Forte inlaid with Sattinwood and of beautiful Mechanism” were sold at an auction. The largest single expense in a statement for the Subscription Assemblies 1814 was £22 15s Od for “Music for the season.”

By the 1820s, there were occasional public concerts. But when a company from Rochester, New York, presented Samuel Arnold's opera The Mountaineers on 22 December 1825 at Mr. Frank's Assembly Room, it was the first time that William Lyon Mackenzie, editor of the Colonial Advocate, had been to a theatre in North America since his arrival five years earlier. The company of Emanuel Judah — seven singers and one dancer — presented Stephen Storace's No Song, No Supper in 1826. The same two operas were heard again in 1828. The first theatre building, a converted Methodist chapel, opened only in 1834.

Notable Performers and Performances

Visiting artists of international fame appeared from the 1840s onward; among the first were John Braham (1841, 1842), Ole Bull (1844, 1853), Anna Bishop (1848, 1851, etc.), the Germanians (an orchestra; 1850, 1852, 1856), Jenny Lind (1851), Adelina Patti (1853, 1860, etc.), Henriette Sontag (1854), Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1856, 1862, etc.), Sigismund Thalberg (1857, 1858), Henri Vieuxtemps (1858, 1870, 1871), Frantz Jehin-Prume (1865, etc.), Pablo de Sarasate (1870), Anton Rubinstein (1872), Henri Wieniawski (1872) and Hans von Bülow (1876). Many of these artists performed at St. Lawrence Hall, opened in 1850. The Royal Lyceum Theatre, opened in 1848, accommodated larger-scale musical and non-musical shows in Toronto. However, programs of operatic excerpts and truncated versions of popular operas given by four or five performers were more frequent than were complete performances.

Norma, given 8 July 1853 at the Royal Lyceum by the visiting Artists' Italian Opera, was the first grand opera, complete with orchestra and chorus, to be presented in Toronto. Rosa Devries sang the title role and Luigi Arditi conducted. Thereafter, touring companies visited the city regularly, and by the beginning of the 20th century most of the popular Italian and French repertoire had been heard.

In 1883, Emma Albani made her first Canadian appearance in 20 years in a complete opera (Lucia di Lammermoor), as a member of Col. Mapleson's Opera Company. The company's second production was Il Trovatore. According to Arcadia (Montreal, 1891–12), in the 1890–91 season 91 performances of 24 works were given in Toronto, though only four were grand operas: Lohengrin, Rigoletto, Carmen, and Les Huguenots. A company of singers from the Metropolitan Opera, including Marcella Sembrich, Edouard de Reszke and Emma Calve, performed The Barber of Seville, Faust, and Carmen in 1899 at the Grand Opera House, a theatre opened in 1874 after the Royal Lyceum had burned down.

Fortunately for Torontonians, many famous American bands and orchestras visited the city with increasing frequency during the last quarter of the century. Bands led by Patrick Gilmore, Victor Herbert and John Philip Sousa delighted audiences. The first visit of the Theodore Thomas Orchestra in 1873 was followed by that of many other excellent groups. Thus, before the end of the century, Beethoven's 5th (1882), 6th (1892) and 7th (1892), Dvořák's New World (1895), and Tchaikovsky's 6th (1896) symphonies, had been performed in the city. Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4 was heard in 1896, the No. 5 in 1882.

Local operatic production was unsuccessful. A few operas were presented in concert form — e.g., Il Trovatore and La Sonnambula in 1866 by the Musical Union under John Carter — but the only company to produce opera on a regular basis was the Holman English Opera Troupe, resident 1867–73 at the Royal Lyceum. After 1910, Toronto was on the circuits of the Montreal Opera Company and the San Carlo Opera.

Notable Local Figures and Groups

Despite the number and importance of visiting artists, most concerts were produced by local musicians. Among the leading mid-19th-century figures were the conductor, organist and composer J.P. Clarke, the singer J.D. Humphreys, the University of Toronto's president John McCaul, the music dealers Abraham and Samuel Nordheimer, the Schallehn brothers, the organist and choirmaster John Carter, and the pianist and teacher G. W. Strathy. Local groups date back at least to 1822, when the West York Militia Band played at the Orange Order celebrations of 12 July 1822. A group of amateurs organized the Toronto Musical Society in 1835, and a Harmonic Society gave concerts in 1840.

The first church organ was probably the one at St. James's Anglican Cathedral ca. 1832. Apart from two pages of “Bugle sounds” issued in 1830, the first music published in Toronto (though actually printed in New York) was William Warren’s A Selection of Psalms and Hymns (1835). These firsts are evidence of the close relationship between music and religion that characterized 19th-century Toronto. The predilection for choral singing and the taste for oratorio were the results. Until the mid-20th century, nearly all the leaders in the city’s musical life were also the leading figures in Protestant church music.

The first substantial choral-orchestral organization, however, was the Toronto Philharmonic Society of 1845–47. The initiator and guiding spirit of this group, and of several of its successors, was McCaul, the musical leader, Clarke. The fortunes of the Philharmonic were uneven, as were those of the Toronto Vocal Music Society (1851–53); the Metropolitan Choral Society, founded in 1857 by Martin Lazare; the Musical Union, formed in 1861 by John Carter; and other groups. However, these groups introduced Toronto audiences to many of the classical overtures, symphonies and oratorios, even though the larger works were often limited to excerpts. An early exception was Handel's Messiah, performed 17 December 1857 by the Sacred Harmonic Choir under Carter; another, his Judas Maccabaeus presented (with an unspecified chorus) under the Rev G. Onions in 1858. Within a few days of one another, in September of that year, the Sacred Harmonic Choir under Carter and the Metropolitan Choral Society under Lazare each performed Haydn's The Creation.

Apart from a volunteer militia band — the Queen's Own Rifles of Canada Band, organized in 1862 under the direction of Adam Maul and continuing to flourish in 2022 — the only stable ensembles in Toronto were those founded after Confederation. The Philharmonic Society was revived in 1872 with J.P. Clarke as conductor. It achieved great distinction 1873–94 under his successor, F.H. Torrington. Nearly as important was Edward Fisher's Toronto Choral Society (1879–91). Many other societies were formed, dissolved, and re-formed in the last quarter of the century. Some of them used the same names as their predecessors, and their activities ranged from serious musical performance to popular quasi-educational meetings for those interested in learning to read music and to sing.

Among the choir directors were Humfrey Anger, Arthur E. Fisher, John W.F. Harrison, Elliott Haslam, J.D.A. Tripp, and A.S. Vogt. Their societies presented Toronto with a widely varied vocal repertoire, from solo songs and glees to the choral masterpieces of Gounod, Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn and Schumann. Cantatas and oratorios won a much warmer reception in the city than did operas. Since orchestras had to be assembled for oratorio and other major presentations, programs also would include overtures or even symphonies and concertos.

All attempts at forming regular orchestras failed, however. Strathy had tried it in 1867, Torrington in 1877. The latter was able to assemble 100 instrumentalists for the festival of 1886, the largest enterprise of the Toronto Philharmonic Society. But although he established an Orchestral School at his Toronto College of Music, Torrington had to rely once again on an ad hoc ensemble for the festival of 1894, which marked the opening of Massey Music Hall (later known as Massey Hall, Canada's most famous concert auditorium). A Toronto Symphony Orchestra formed by Francesco D'Auria in 1891 was short-lived, as was the Toronto Permanent Orchestra, optimistically inaugurated by Torrington in 1900.

Toronto had to wait several more years for its first enduring orchestra, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, formed by Frank Welsman in 1908 on the basis of the Toronto Conservatory Orchestra he had established two years earlier. Welsman's orchestra introduced to Torontonians the classical symphonies and works by Debussy, Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss and Wagner. It also accompanied Elman, Carreño, Kreisler, Rachmaninoff, Schumann-Heink, and other celebrities. Personnel shortages forced its eclipse before the end of the First World War.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Toronto was justifiably known as “the choral capital of North America.” This fame was based on several new concert choirs and a multitude of fine church choirs. Albert Ham led the National Chorus (1903–28), Edward Broome led the Toronto Oratorio Society (1910–12 and 1914–25), and Herbert M. Fletcher led two “graded” choirs formed in 1904: the People's Choral Union for beginners and the Toronto Choral Union (later renamed Schubert Choir) for advanced choristers. Both were active until the war. There was even a Young Socialist Choir (1914–17). But the most important and long-lived group proved to be the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir. Established in 1894 by A.S. Vogt to perform unaccompanied works, the choir was disbanded in 1897 and reorganized in 1900 on a larger scale. After 1904, the choir made frequent visits to the USA, while American orchestras joined it (and some of the other large choirs) in concerts and oratorio presentations.

The first string quartet in Toronto was likely one formed by the violinist Ferdinand Griebel ca. 1856. An increase in chamber music concerts during the 1880s resulted directly from the expansion of music education in this decade. The musicians who came together as teachers at the newly established conservatories formed such ensembles as the Toronto String Quartet(te) (1884), the Conservatory String Quartet (1901), the Brahms Trio (ca. 1909), the Hambourg Trio (1912), the Academy String Quartet (ca. 1912), the Schumann Trio, and the Toronto Ladies Trio. Prominent chamber music players included John Bayley, Frank Blachford, Bertha Drechsler Adamson, A.E. Fisher, the Hambourg brothers, Heinrich Klingenfeld, Luigi von Kunits, Carl Martens, Leo Smith, Richard Tattersall, and Frank Welsman. Some chamber music recitals took place under the auspices of the Women's Musical Club beginning in 1899.

Queen's Own Rifles Band, Toronto, 1909

(Wikimedia Commons)

Music Education

During the greater part of the 19th century, specialized music teaching was exclusively in the hands of individual musicians. In addition to their private teaching many also held part-time posts in private schools. After 1844, when Egerton Ryerson became chief superintendent of education in Upper Canada, vocal music gained an important place in the public elementary school curriculum. The Toronto Normal School, opened in 1847, appointed a music instructor the following year. The leading school music educators during the following decades were H.F. Sefton, S.H. Preston, and A.T. Cringan.

The rise of a prosperous middle class made possible the establishment of conservatories. The Canadian Conservatory (1876) may have been the first; another short-lived music school under the direction of J. Davenport Kerrison followed 1878–87. The Toronto Conservatory of Music, founded in 1886 by Edward Fisher, continued to flourish in 1991 as The Royal Conservatory of Music. Other schools included the Toronto College of Music, founded in 1888 by F.H. Torrington; W.O. Forsyth'sMetropolitan School of Music, founded in 1893 and absorbed in 1912 by the Canadian Academy of Music (founded in 1911 and financed by Albert Gooderham); and the Hambourg Conservatory of Music, founded in 1911.

Although both the University of Toronto (King's College until 1850) and the University of Trinity College conferred B MUS degrees early in their histories (respectively on James P. Clarke 1846 and George W. Strathy 1853), they set up examination systems only in the 1880s (Trinity) and 1890s (Toronto), without, however, offering regular instruction. Instead, the preparation of candidates was left to certain affiliated conservatories.

Instrument Building and Music Publishing

The foundations laid in the 1840s by such pioneer piano builders as J. and J. Mead, O'Neill Brothers, and J.M. Thomas, and by the music dealer-publishers A.&S. Nordheimer, paved the way for Toronto's national supremacy in instrument building and music publishing. Probably the first keyboard instrument manufactured in York was the “fine-toned and handsomely ornamented Chamber Organ” offered for sale in 1825 by Richard Coates. In the second half of the 19th century Gourlay, Winter & Leeming; Heintzman; Gerhard Heintzman; Mason & Risch; Newcombe; and Nordheimer were among prominent piano builders. Edward Lye, S.R. Warren & Son, and R.S. Williams were major pipe and reed organ makers. In 1913, the Canadian Courier claimed that “Toronto alone produces more pianos than New York, Chicago or Philadelphia.” Of the many retail music dealers who imported and published music, Anglo-Canadian Music Co, Nordheimer, Suckling & Sons, and Whaley Royce were by far the most productive.

Among the journalists and critics who contributed to the discussion of music were Augustus Bridle, Hector Charlesworth, Edwin Parkhurst, and Edward Schuch. The first Canadian music periodicals in English were published in Toronto, among them George F. Graham's Canadian Musical Review (1856), Musical Galaxy (1875), and the Musical Journal (1887–90?). Much longer runs were achieved by the Canadian Music Trades Journal (1900–33) and Musical Canada, begun in 1906 as The Violin and continuing until 1933.

1919–45

Unfortunately, the First World War interrupted or terminated many worthwhile activities. In the next period of Toronto's history, the rise in popularity of the gramophone and radio, the hardships of the Great Depression, and the increased ethnic diversity of the population changed the emphases of musical culture. On the one hand, music became a more passive amusement, while on the other hand, new standards of professional accomplishment were introduced.

The cultural climate at the beginning of the century is summed up in Maurice Solway's Recollections of a Violinist (p. 17): “this is not to say that before the waves of immigrants at the beginning of the century Toronto had no music; it is just that much of the music-making fell under the category of cultivated amateurism, and what professionalism there was tended to find its outlet in popular music. A good example of this last was military and brass band music, which truly cut across all ethnic and social barriers in its appeal.”

During the 1920s, the accompaniment of silent films, of vaudeville, and of other theatrical entertainment provided a measure of employment for orchestral musicians. Examples were the extravaganzas produced by Jack Arthur at Shea's Theatre after 1918. In the 1930s, talking movies made the movie house orchestras obsolete. But Toronto became the centre of English-language radio broadcasting, supplying musicians with new opportunities. As early as 1922, the Romanelli Orchestra had participated in a broadcast, the first by an orchestra in Canada. Luigi von Kunits, who founded the New Symphony Orchestra in 1923 (the Toronto Symphony Orchestra after 1927), recognized the potential of broadcasting. In 1929, he and members of the TSO inaugurated North America's first transcontinental radio series. Von Kunits' successor, Sir Ernest MacMillan, expanded the length and number of annual concerts and, during his 1931–56 tenure, developed the orchestra into a first-rate ensemble. Other orchestras in the inter-war years included the Toronto Conservatory SO under Donald Heins and later Ettore Mazzoleni, the University of Toronto SO founded by John Weinzweig, and the Promenade Symphony Concerts under Reginald Stewart.

Symphonic and Choral Music

In both symphonic and choral music, Stewart and MacMillan were rivals during the 1930s. In addition to leading the TSO, MacMillan gave annual performances of Bach's St Matthew Passion with the TCM Choir. Stewart and his Toronto Bach Choir presented the St John Passion annually 1933–41.

Although no longer so predominantly devoted to choral music, Toronto still produced many new choral groups. These included the Orpheus Society, founded in 1920 by Dalton Baker; the Coliseum Chorus (later the Canadian National Exhibition Chorus), under H.A. Fricker (1922–34); the Hart House Songsters and Canadian Singers, founded 1924 by Campbell McInnes; the Hart House Glee Club (1933-72); the Bishop Strachan School Chapel Choir (founded 1925); the Freiheit Gezangs Farein, founded in 1925 and succeeded in 1934 by the Toronto Jewish Folk Choir; Healey Willan's Tudor Singers (1933–40) and St Mary Magdalene Singers (founded 1939); the Toronto Men Teachers' Choir (1941–76); and the Harvey Perrin Choir (1944–56). The Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, under H.A. Fricker 1917–42, continued to be a centre of musical life.

Opera and Musical Theatre

Between the two world wars, visits to Toronto by the San Carlo Opera Co. were frequent. Efforts to establish a permanent local opera company were persistent, but futile. Several amateur groups specializing in Gilbert & Sullivan did achieve a measure of continuity, however. Among these were the Savoyards, founded in 1919 by George and Reginald Stewart; the Eaton Operatic Society (1931–65); the Canada Packers Operatic Society (1942–55); and the Toronto Light Opera Society, founded in 1943 by Frederick and Howard Mawson.

The TCM's Conservatory Opera Company, begun by MacMillan during the late 1920s, failed during the Depression. Beginning in 1936, Harrison Gilmour's Opera Guild of Toronto and Braheen Urbane's Canadian Grand Opera Association competed for audiences and funds. These companies brought to the stages of the Royal Alexandra, Massey Hall and Maple Leaf Gardens several operas, including Aida, Faust, Cavalleria Rusticana, I Pagliacci, Tosca, Rigoletto, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin. Although Urbane's company was short-lived, Gilmour's continued to produce operas sporadically even after the outbreak of the Second World War. During the 1940s, the Rosselino Opera Co. sought to provide young performers with experience.

Chamber Music

Less hindered by financial vicissitudes than opera and better able to capitalize on the opportunities provided by broadcasting, chamber music was relatively active. The Hart House String Quartet (1923–45) became Canada's most famous chamber ensemble of the day and one of the few to tour abroad then. Other groups included the Five Piano Ensemble (see Piano Teams), formed in 1926 by Norah de Kresz, Alberto Guerrero, Viggo Kihl, Ernest Seitz, and Reginald Stewart; the Conservatory Trio (1926); the revived Conservatory String Quartet (1929); the Ten-Piano Ensemble, organized in 1931 by Mona Bates; the Toronto Chamber Music Society, founded in 1931 by A.D. Jordan; the New World Chamber Orchestra, founded and conducted 1932–40 by Samuel Hersenhoren; the Canadian Trio, formed in 1941 by Kathleen Parlow, Zara Nelsova, and Sir Ernest MacMillan; and the Parlow String Quartet (1941-58).

Bands and Competitions

At the Canadian National Exhibition (opened as the Industrial Exhibition in 1879 and renamed CNE in 1904), military bands had long been a main attraction. A.L. Robertson helped to organize a band competition in 1921 and continued to administer it for nearly 40 years. Toronto bands of this period included those of the Queen's Own Rifles, the Toronto Regiment (conducted 1926–58 by the musicians' union official Walter Murdoch), and the Royal Regiment of Canada. Richard Hayward founded the Toronto Police Band in 1926 and led the Toronto Concert Band 1925–39. L.F. Addison formed the Toronto Symphony Band in 1935 and John Slatter led the 48th Highlanders Band 1896–1946. Bands also competed in the Kiwanis Music Festival, the first of which was held at Eaton Auditorium in 1944.

Music Education

Many of the musicians just named were among the foremost teachers of the period. For the institutions at which they taught, the 1920s and 1930s were years of consolidation and retrenchment after the earlier growth spurt. The Canadian Academy of Music and the Toronto College of Music, amalgamated in 1918, were absorbed in 1924 into the TCM. In 1921, it was placed under the jurisdiction of the board of governors of the University of Toronto. A Faculty of Music, set up in the university in 1918 as an entity separate from the TCM, in fact maintained intimate links with it; from 1918 to 1942, the dean of the faculty and the principal of the TCM were the same person, first A.S. Vogt and later Ernest MacMillan. The latter, through the combination of these and other positions, occupied a position of influence and prestige in his city unique in the musical history of Canada.

School music in this period owed much to the efforts of A.T. Cringan, Duncan McKenzie, Emily Tedd, Eldon Brethour, and other supervisors and teachers.

Music Writing and Associations

Toronto music critics and journalists of the period 1918–45 included Augustus Bridle at the Toronto Daily Star, Lawrence Mason at the Globe, and Hector Charlesworth at Saturday Night. Bridle had been instrumental as well, in 1908, in creating the Arts and Letters Club, which counted among its members many of Toronto's prominent musicians. A variety of other organizations came into being in this period. The Canadian Bureau for the Advancement of Music, chartered in 1919, and the Canadian Performing Rights Society (1925–45; CAPAC thereafter) were national in scope; the Ontario Music Educators' Association, founded in 1919, and the Ontario Registered Music Teachers' Association, founded in 1936, were of provincial significance; while the Vogt Society, founded in 1936, was of local importance.

Music Publishing and Recording

New music publishing firms established in Toronto included Canadian Music Sales and Gordon V. Thompson. Boosey & Hawkes of London opened a Toronto branch, and the Toronto office of Oxford University Press created a music department. The number of piano manufacturers declined, but a new organ factory was opened in 1919 by Franklin Legge. (See Organ Building.)

Toronto also became a centre of the recording industry at this time. Recording companies that had offices or Canadian headquarters in Toronto included Columbia Records ( Sony) and Brunswick. Among violin makers and repairers in Toronto, the most prominent have been George Kindness (1911–60s) and George Heinl, who opened in 1912 an establishment that continued to do business in 1991.

1945–Present

The post-war period saw an enrichment of musical life in Toronto commensurate with the notable growth of the city's population and wealth. Toronto benefited greatly from the increased post-war government financing of the arts, education and broadcasting. It also became a centre for rock and jazz, with excellent broadcasting and recording facilities. In addition, the significant wave of new immigration added a great variety of professional skills and popular traditions to the fabric.

Groups and Organizations

After the Second World War, the city's most distinguished performing groups, the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir and the TSO, continued to appear at Massey Hall, the Ontario Place Forum (opened 1971), and elsewhere. In 1956, after his 25th season as conductor of the TSO, Sir Ernest MacMillan resigned. Subsequent conductors of the TSO (TS after 1967) were Walter Susskind (1956–65), Seiji Ozawa (1965–69), Karel Ančerl (1969–73), Victor Feldbrill as resident during two seasons of guest conductors (1973–75), and Andrew Davis, who succeeded Ančerl in 1975 and in 1989 was succeeded by Gunther Herbig. The city’s other two major symphonic organizations were the CBC Symphony Orchestra (1952–64), a full-scale broadcasting orchestra which specialized in contemporary music, and Heinz Unger's York Concert Society (1952–65), which pioneered in the Canadian performance of Mahler.

Among smaller post-war orchestral groups have been the Toronto Women's Orchestra founded in 1948 by Harold Sumberg; the Hart House Orchestra (1954–71) founded by Boyd Neel; the CJRT Orchestra (Toronto Philharmonic Orchestra), founded in 1975 and conducted by Paul Robinson; the Amadeus Ensemble, founded in 1984; and the National Chamber Orchestra of Canada, founded in 1984 and conducted by Sasha Weinstangel. Tafelmusik, founded in 1978 and directed by Jean Lamon beginning in 1981, and the Esprit Orchestra, founded in 1984 and conducted by Alex Pauk, have specialized in period instrument and contemporary orchestral music performances, respectively. Community orchestras such as the Harmony Symphony Orchestra (founded by Arthur Semple ca 1919), the East York and North York Symphony Orchestras, the Etobicoke Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Mississauga Symphony Orchestra also have added to Toronto-area concert life. (See also Orchestras.)

Toronto audiences have supported a number of performing groups and concert societies devoted to music of the avant-garde, such as ARRAYMUSIC, the Artists' Jazz Band, the Lyric Arts Trio, and Nexus, as well as the series offered by Ten Centuries Concerts, the Isaacs Gallery Concerts (and others of Udo Kasemets), New Music Concerts, and the Music Gallery.

Choral Music

Toronto has sustained its excellent reputation as a choral centre. Elmer Iseler and the Festival Singers (1954–79) set a new standard for choral singing in Toronto and Canada, carried on by the Elmer Iseler Singers (founded in 1979). Under Iseler's direction, these choirs and the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir enjoyed international recognition. Other choral groups have included the Leslie Bell Singers, the Don Wright Chorus (1957–62), Roman Toi's Estonian Mixed Choir (1957–72; see also Estonian Music in Canada), and the Orpheus Choir, founded by John Sidgwick in 1964. Other ethnic, school, and church choirs too numerous to name have carried on Toronto's amateur choral tradition.

Chamber Music

Chamber music received a boost after the war when the Women's Musical Club resumed its concert series (1946) and Walter Homburger, through his International Artists Concert Agency, presented recitalists of world renown. Many new chamber ensembles were formed, among them the Sumberg-Ysselstyn-Guerrero Trio (late 1940s); the Solway String Quartet (1947-early 1970s); the Marcus Adeney String Quartet (1950s); the Dembeck String Quartet (1950–61); the Spivak String Quartet (1951–56); the Pack Trio (formed 1955); the Galant Chamber Music Players (founded 1956 by Berul Sugarman); the Jack Groob Trio (formed 1956); the Toronto Woodwind Quintet (founded 1959); the Canadian String Quartet (1961–63); William Kuinka’s Toronto Mandolin Chamber Ensemble (1964–69); the Orford String Quartet (1965–91 and regarded as the country's foremost quartet of its time); the Chamber Players of Toronto (founded 1968); the Brodie Saxophone Quartet (founded 1972); the York Winds (1972–88); Camerata (founded 1972 by Elyakim Taussig); the Ararat Trio (1973–76; Gerard Kantarjian, Gisela Depkat, and Raffi Armenian); Peggie Sampson’s Quatre en Concert (formed 1978); the University of Toronto Faculty Trio (formed 1974 by Lorand Fenyves, Vladimir Orloff, and Patricia Parr); the Gadar Trio (formed 1976 by Kantarjian, Rivka Golani, viola, and David Miller, cello); Canadian Brass (which moved in 1976 from Hamilton to Toronto); and Amici (formed 1986 by Parr with David Hetherington, cello and Joaquin Valdepeñas, clarinet).

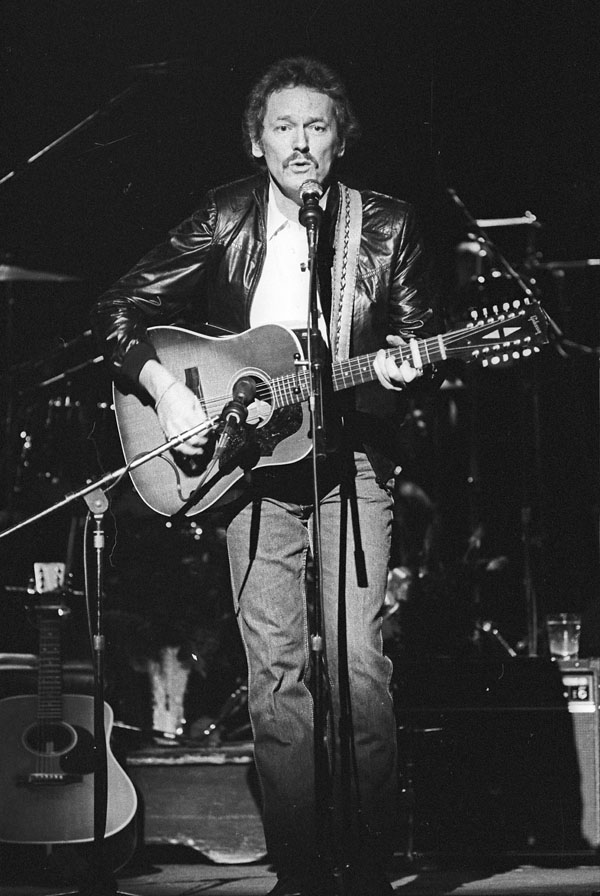

Of pianists who lived in Toronto during the period 1950–90, Glenn Gould, Oscar Peterson and Anton Kuerti achieved the greatest recognition nationally and internationally. Of singers who lived there during the same period, Maureen Forrester, Lois Marshall and Louis Quilico enjoyed world fame. Other noted residents included the pianist Antonín Kubálek, the clarinetist James Campbell, the singers Mary Morrison and Patricia Rideout, the harpsichordist Greta Kraus, the teacher Boris Berlin, the pianist-accompanists Leo Barkin and George Brough, the folk singers Buffy Sainte-Marie, Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot, and country singer Anne Murray.

Opera and Musical Theatre

In the late 1940s, Herman Geiger-Torel, Nicholas Goldschmidt, Ettore Mazzoleni, and Arnold Walter began to work to establish the permanent opera company that had eluded all previous pioneers. Like the TSO, the Canadian Opera Company (COC) had its roots in the RCMT. The Royal Conservatory Opera School (University of Toronto Opera Division), established in 1946, has produced singers who have helped ensure the permanence not only of the COC but of other Toronto groups and companies all over Canada. The Canadian Children's Opera Chorus, founded in 1968, has participated in many COC and Toronto area productions.

Among post-war endeavours in musical theatre have been the CBC Opera Co. (1948–55), Spring Thaw (1948–71 and 1980), Melody Fair (1951–54), Giuseppe Macina's Toronto Opera Repertoire (founded 1968), Opera in Concert (founded 1974 by Stuart Hamilton), Co-Opera Theatre (formed 1975 by Raymond Pannell), COMUS Music Theatre (active 1975-87), Opera Atelier (established 1983), Toronto Operetta Theatre (founded 1985, Guillermo Silva-Marin artistic director), and Opera Ora Now (founded 1988 by Julia Iacono).

Did you know?

Between 1955 and 1975, Toronto musicians developed what came to be known as the “Toronto Sound.” It was a mix of rockabilly (e.g., Little Caesar and the Consuls, Richie Knight and the Mid-Knights, Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks), blues (e.g., David Clayton-Thomas and the Shays) soul and R&B (e.g., Jackie Shane), psychedelic rock (e.g., Kensignton Market, the Mynah Birds) and reggae (e.g., the Rivals, the Sheiks, the Cougars, the Cavaliers). The influence of the latter can also be heard in the music of such Toronto rappers as Maestro Fresh Wes and Kardinal Offishall and such R&B singers as Deborah Cox and Jully Black. More recently, the Toronto Sound has come to refer to the dark, introspective, R&B-infused hip hop of global superstars Drake and The Weeknd. It is characterized by what Vice has called an “icy, detached sensuality [that] … communicates a sense of cool but also intense emotion that other regional scenes can’t imitate.”

Concert Halls and Series

The expanding concert life of the city was served by several new halls, including MacMillan Theatre and Walter Hall at the Edward Johnson Building, University of Toronto, and Town Hall at the St Lawrence Centre. Roy Thomson Hall, a new hall to take over the main functions of Massey Hall, was opened in 1982. Restoration of the Elgin, the Winter Garden, and the Pantages theatres provided further venues for musical performances. The CBC also finally opened new quarters, with excellent studio facilities, on Front Street in 1992.

The city has enjoyed numerous concert festivals devoted to the works of individual composers (e.g., Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Messiaen, Mozart, and Schubert), although by 1990 a continuing annual concert festival had not been established, despite numerous attempts. However, long-lasting performance festivals in other areas have included the May (or Spring) at Massey Hall, established in 1886 for choirs and performing groups from the city's public schools; the festivals of ethnic groups such as the Latvians, the Chinese, and the West Indians (Caribana); the annual multi-national celebrations of Caravan, established in 1969; and the Mariposa Folk Festival. There have also been many noteworthy special events, from the Toronto Musical Festival of 1912 to the 1989 International Choral Festival.

Music Education

Education in all fields of music was reorganized and improved after the Second World War. New programs in school music, which significantly increased the numbers of teachers, students, and aspiring performing artists, were created by C. Laughton Bird, Keith Bissell, Jack Dow, and Harvey Perrin at the elementary and secondary levels and by Robert Rosevear at the post-secondary level. To satisfy the growing interest in the accordion, guitar, saxophone, and recorder, Eric Mundinger, Eli Kassner, Paul Brodie, and Hugh Orr established private schools or studios, and Joseph Macerollo pioneered free-bass accordion classes at the RCMT.

The RCMT and University of Toronto Faculty of Music moved to larger quarters, and in 1968 a new music department was organized at York University. Those responsible for these schools have included Ettore Mazzoleni, Arnold Walter, Boyd Neel, John Beckwith, Gustav Ciamaga, Carl Morey, David Ouchterlony, Ezra Schabas, Robert Dodson, Gordon Kushner, and Peter C. Simon and, at York, Austin Clarkson, Sterling Beckwith, Alan Lessem, James McKay, and David Mott. Community colleges such as George Brown, Humber, and Seneca have also offered study programs and special events. Humber College’s jazz program has come to be recognized as one of the best music programs in the country. The librarians Jean Lavender, Kathleen McMorrow, Ogreta McNeil, and Isabel Rose and the sound archivist and discographer James Creighton built up for Toronto the foremost musical research and listening facilities in Canada.

For school choirs and instrumental ensembles, and for student singers and instrumentalists of all grades, the Kiwanis Festival continued in 1980 to provide opportunities to evaluate their achievements through competition, as did the annual competitions held during the CNE. The National Competitive Festival of Music (CIBC National Music Festival), established in 1972 at the CNE, gave top winners from Kiwanis and other competition festivals across Canada a chance to compete for higher honours.

As the hub of musical activity in all genres — classical, avant-garde, church, pop, jazz, commercial, etc. — in English-speaking Canada, Toronto has become a headquarters for many arts organizations, a concentration which is felt by some critics to be excessive. Toronto is home to the national offices of ACO, the CLComp and Canadian Music Centre, the CMPA, the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, the Canadian Bureau for the Advancement of Music, the NYO, and SOCAN. For years, it was the seat of the Canadian Music Council and the CCA. It became the headquarters for several provincial organizations as well, including the OAC, OFSO, the Ontario Choral Federation, and Prologue to the Performing Arts.

Notable Composers

Composers resident in Toronto after the Second World War have included Lucio Agostini, Robert Aitken, Louis Applebaum, John Beckwith, Norma Beecroft, Keith Bissell, Walter Buczynski, Gustav Ciamaga, Michael Colgrass, Gordon Delamont, Samuel Dolin, John Fodi, Harry Freedman, Srul Irving Glick, John Hawkins, Udo Kasemets, Talivaldis Kenins, Lothar Klein, Edward Laufer, Alexina Louie, William McCauley, Ben McPeek, John Mills-Cockell, Oskar Morawetz, Phil Nimmons, Raymond Pannell, Alex Pauk, Tibor Polgar, Godfrey Ridout, Harry Somers, Ann Southam, Morris Surdin, Norman Symonds, John Weinzweig, and Healey Willan. Among them, Applebaum, Bissell, Buczynski, Glick, Mills-Cockell, Pauk, Ridout, Somers, Surdin, and Weinzweig were born in Toronto.

Music Publishing and Recording

The many facets of the city's musical life have been assessed by such critics as John Beckwith, Leslie Bell, Robert Everett-Green, Udo Kasemets, John Kraglund, William Littler, and Kenneth Winters.

In music publishing Toronto flourished, although most of the activity was in the distribution of foreign imports. But the newly established branches of such foreign firms as Chappell & Co. (Warner/Chappell), Leeds Music, and G. Ricordi & Co. did their share of Canadian publishing. New publishers were Berandol Music, Jarman Publications, and E.C. Kerby. Berandol was preceded by BMI Canada (PRO Canada), which, though primarily a performing rights organization, in the years 1947–65 built the largest catalogue of Canadian music in print. A decline set in about 1970 and by 1991 only a few music publishers remained active.

Many phonograph and recording companies that flourished during the 20th century had offices in Toronto. In addition to the aforementioned Columbia and Brunswick, these companies included Quality Records (1950), Beaver (1950), Hallmark (1952), Capitol (1954), Rococo (mid-1950s), Arc (1958), Canadian Talent Library (1962), Nimbus 9 (1968), GRT (1969), A & M (1970), True North (1970), Boot (1971), Attic (1974), Berandol (1975), Centrediscs (1981), and Duke Street Records (1983). By the 1970s, Toronto had become a recording studio centre of international importance.

Notable Toronto-born Musicians

|

John, Murray, and Frances Adaskin |

|

|

Geddy Lee (see Rush) |

|

|

Charlie Angus |

|

|

Ammoye |

Raine Maida (see Our Lady Peace) |

|

Bahamas |

|

|

Leslie Barber |

|

|

Goldy McJohn (see Steppenwolf) |

|

|

Emilie-Claire Barlow |

|

|

Dave Bidini (see Rheostatics) |

|

|

Stuart Broomer |

|

|

Mavor Moore |

|

|

Carl Morey |

|

|

Elizabeth Campbell |

|

|

Brendan Canning (see Broken Social Scene) |

Albert and Gerald Nordheimer |

|

Tommy Common |

|

|

Alan Detweiler |

John Perrone |

|

Wray Downes |

|

|

Kevin Drew (see Broken Social Scene) |

|

|

Robert Reid |

|

|

Jack Richardson |

|

|

Gil Evans |

|

|

Robert and Dennis Farnon |

|

|

Ted Roderman |

|

|

Hyman and Erica Goodman |

|

|

Teresa Gray |

|

|

Douglas Stanbury |

|

|

Warren Kirkendale |

|

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom