Track and field (or athletics) is a composite sport that includes competitions in walking, running, hurdling, jumping (high jump, pole vault, long jump, triple jump), throwing (javelin, discus, shot put, hammer) and multiple events, such as the decathlon and heptathlon. At the Olympic Summer Games, the sport’s best-known competition, there are 47 events: 24 for men and 23 for women. More national communities compete at the Olympics in track and field than in any other sport. Since 1900, when George Orton won the 2500m steeplechase at the Olympic Games in Paris, Canadians have competed on the world stage, with several winning Olympic or world championships in track (Percy Williams, Donovan Bailey, Perdita Felicien) and field (Ethel Catherwood, Duncan McNaughton, Derek Drouin).

Early Athletics in Canada

The origins of Canadian track and field can be found in the running and throwing competitions of indigenous peoples, the colonial athletics of British officers and civil servants, the Caledonian Games of Scottish immigrants and the tests of strength at rural “bees” and fairs. In August 1844, Montréal’s Olympic Club staged a two-day event that they called “the Montréal Olympic Games,” featuring track and field events as well as a lacrosse competition between a white team and indigenous team. By Confederation in 1867, highly competitive meets and match races were a regular part of the sporting scene. Perhaps the most popular event was the professional pedestrian, or “go-as-you-please,” race, in which competitors ran or walked to achieve a maximum distance within a fixed time, which was often six days.

In 1884, representatives from athletic clubs in Ontario and Québec formed the Canadian Amateur Athletics Association. The organization was known as the Canadian Track and Field Association (CTFA) from 1909 to 1991, after which it became known as Athletics Canada.

Until 1968, the CTFA operated under the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) of Canada. With AAU control came strict amateurism — the belief in the moral superiority of participation for its own sake, without any material reward, enforced through a list of prohibitions governing eligibility. This effectively limited participation to those individuals who enjoyed the leisure and the financial means to pursue the sport on their own and those educational and social institutions (universities, YMCAs and police athletic associations) that accepted the accompanying ideology of self-improvement.

Until the 1920s, the men who controlled the sport were successful in keeping women out on the dubious grounds that vigorous physical activity would damage their reproductive organs and was “unseemly.” In the 1920s, however, pressure from women forced the AAU to create a women’s committee and the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) to include women’s events in the Olympic Games.

International Competition to the 1960s

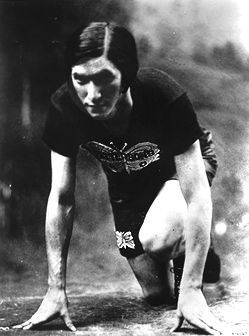

Hamilton sprinter Robert Kerr used his blazing start to dominate Canadian, American and British Empire competitions and won gold and bronze medals at the 1908 Olympic Games in London. A great era of Canadian sprinting began at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, where Vancouver’s Percy Williams won both the 100 m and 200 m sprints with his spectacular leaping finish, and Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld, Jane Bell, Ethel Smith and Myrtle Cook combined to capture the first-ever 4x100 m women’s relay. Over the next decade, Canadian sprinters won another six medals at the Olympics and 22 at the British Empire Games. These feats were not equalled until the 1960s, when Vancouver’s Harry Jerome tied the world record for 100 m and won Commonwealth and Pan American championships, as well as an Olympic bronze medal.

Canadian middle-distance runners also excelled in international competition. Before he won Canada's first Olympic gold medal in the 2500 m steeplechase at the Paris Games of 1900, Toronto miler George Orton had compiled a long string of championships and records. In the interwar period, Phil Edwards and Alexander Wilson brought back seven medals from three Olympics. In 1954, Rich Ferguson placed third in the famous “Miracle Mile” confrontation between Britain’s Roger Bannister and Australia’s John Landy at the Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, which was won by Bannister. In the 1960s, Toronto’s Bill Crothers, one of the most graceful runners of all time, dominated the 1,000-yard event on the North American indoor track circuit and won a silver medal at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo.

Canadian distance runners won marathon titles at the Olympics (Billy Sherring in the now unrecognized 1906 Athens Games) and at the British Empire Games (Harold Webster in London in 1934), and won the prestigious Boston Marathon 15 times between 1898 and 1948. Some of these Boston champions, such as Onondaga Tom Longboat (1907), Halifax’s Johnny Miles (1926 and 1929), and Québec’s Gérard Côté (1940, 1943, 1944 and 1948) became legendary figures in the sport.

More than half the medals that Canadians won in international competition came in field events. The strongest tradition was in the high jump, where Ethel Catherwood(1928), Duncan McNaughton (1932) and Eva Dawes (1932) won Olympic medals. Other outstanding Canadian champions include Montréal’s Étienne Desmarteau, who won the 56-pound weight toss at the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis, Canada’s first Olympic gold medal in field events; another thrower, Eric Coy, won gold in discus and silver in shot put at the British Empire Games in 1938. In the pole vault, Ed Archibald won bronze at the 1908 Games in London, while William Happenny won bronze at the 1912 Games in Stockholm; Garfield McDonald took silver in the triple jump at the 1908 Games and Calvin Bricker won medals in long jump at both the 1908 and 1912 Games.

Government Support and Professionalization: the 1960s and 70s

Since the mid-20th century, the structure of Canadian track and field has radically changed. Following the Second World War, Canada’s performance at the Olympics fell behind that of other nations, and Canadian track and field athletes failed to win any medals at either the 1952, 1958 or 1960 Olympic Summer Games. In 1961, the government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker passed the Fitness and Amateur Sport Act to support amateur sports organizations and improve the performance of Canadians in international competition. The Act led to the creation of the Canada Games and national teams (rather than club teams) and provided money for training and travel. This brought about the professionalization of coaching and administration and the recruitment of the medical and scientific communities to the goals of high performance. Previously, the sport was conducted almost entirely by volunteers, who often combined the roles of coaching, officiating and administration, using their homes as offices and financing much of the activity out of their own pockets.

Although Canadian track and field athletes won a silver and a bronze at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, Canada’s poor medal showing at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City (with no medals in track and field) gave rise to demands for further action. The announcement in 1971 that Montréal would host the 1976 Olympic Games provided additional pressure. In 1970–71, a Grants-in-Aid program began for student athletes. Also in 1971, a program called Intensive Care provided funding to support athletes training for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. However, pole vaulter Bruce Simpson’s fifth-place finish was the best by a Canadian track and field athlete at the 1972 Games. Debbie Brill, who had won the 1970 Commonwealth Games title in high jump, placed eighth at the Olympics.

In 1972, the Canadian Olympic Association (COA) and Sport Canada initiated Game Plan, a funding partnership of the federal and provincial governments and the national sports-governing bodies with the objective of lifting Canada into the top 10 nations by the 1976 Montréal Olympics. Game Plan would fund competition tours (such as the first Canada–US dual track meet for women in 1972) and training camps (for example, at Toronto’s Fitness Institute and the National Athletic Training Camp, a converted Canadair hangar in Montréal). In spring 1975, a group including runners Abigail Hoffman and Bruce Kidd lobbied Canada's Olympic committee to provide more assistance to elite athletes, including compensation for lost income while training. Between May 1975 and the 1976 Olympics, some $2.3 million was distributed to about 600 Canadian athletes for training and living expenses. Government support for elite athletes would continue after the 1976 Games; by 1980, Game Plan and the Grants-in-Aid program had been merged into Sport Canada’s Athlete Assistance Program.

The CTFA had its own “game plan” for the 1976 Games in Montréal. In 1973, the CTFA invited Polish sprint specialist Gerard Mach to conduct clinics; soon after, he became Canada’s first professional track and field coach. The CTFA then appointed a technical director, Lynn Davies, and four national coaches: Derek Boosey (jumps and multiple events), Jean-Paul Baert (throws), Paul Poce (distance running) and Gerard Mach (sprints, hurdles and relays).

At the 1976 Olympic Games in Montréal, Canada placed 11th overall in team standings and high jumper Greg Joy won the team’s only medal in track and field. While Canada failed to break into the top 10 at the Olympics — the goal of Game Plan ’76 — it placed first overall at the 1978 Commonwealth Games in Edmonton, two years later. In athletics, gold medals were won by Boris Chambul (discus), Claude Ferrange (high jump), Carmen Ionesco (discus), Diane Jones Konihowski (pentathlon), Phil Olsen (javelin) and Bruce Simpson (pole vault). The track and field team also won eight silver medals and nine bronze medals. At the 1979 Pan American Games in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Canada placed third in the team standings, with track and field athletes bringing home 18 medals. Canadians also did well at the Boston Marathon during this period: Toronto’s Jerome Drayton won the men’s race in 1977, and Montréal’s Jacqueline Gareau won the women’s race in 1980.

International Competition in the 1980s

In 1980, Canada decided to boycott that year’s Olympic Summer Games in Moscow. Led by the United States, the boycott was a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. Despite this setback, the CTFA established “event training centres,” where recognized coaches could work with emerging talent: a Toronto sprint centre under coach Charlie Francis; distance-running centres under coaches Ron Bowker in Victoria and Alphonse Bernard in Winnipeg; and multiple-event centres in Saskatoon under coach-athlete Diane Jones Konihowski and in Toronto under coach Andy Higgins. Trust funds, pioneered in athletics by the CTFA and approved by the IAAF at its 1982 congress, cleared the way for amateur track and field competitors to earn and spend money legally (from corporate sponsorship, commercial endorsement or government grants) for living and training expenses, without losing amateur status.

In 1983, the first-ever IAAF World Track and Field Championships was held in Helsinki, Finland; prior to this, the Olympics were considered the world championships. Because of the African boycott of the 1976 Olympic Games in Montréal and the American boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow, there had not been a world championship in track and field since 1972. Canadians won no medals at the inaugural IAAF championships but placed 11th in the world.

1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Ben Johnson won a bronze in the 100 m and Lynn Williams took home a bronze in the 3000 m. The men’s relay team won bronze in the 4x100 m, and women’s relay teams won silver in both the 4x100 m and the 4x400 m events. In the 1987 Pan American Games, Canadian track and field athletes took seven silver medals and three bronze medals. That year, Johnson established himself as the premier sprinter in the world, setting the record in the 100 m and winning the world championship, as well as breaking two indoor world records in the 60 m (6.41 sec) and 50 m (5.55 sec) races. Also in 1987, Angella Issajenko broke the women’s indoor world record for the 50 m dash (6.06 sec).

1988 Doping Scandal

Canadian track and field suffered a devastating blow when Ben Johnson tested positive for steroids after winning the 100m gold medal at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, overshadowing Dave Steen’s accomplishment in taking the bronze medal in the prestigious decathlon later in the Games.

Following the drug scandal at Seoul, the federal government established the Commission of Inquiry Into the Use of Drugs and Banned Practices Intended to Increase Athletic Performance (Dubin Inquiry), which heard shocking testimony from coach Charlie Francis and sprinter Angella Issajenko, among others, about the widespread use of performance-enhancing substances. The inquiry revealed that, encouraged by coach Francis, a number of Canadian sprinters had knowingly taken steroids provided by Dr. George (Jamie) Astaphan. This included not only Johnson and Issajenko, but also Mark McKoy, Desai Williams and Tony Sharpe. As a result of Dubin’s report, Canada strengthened its drug-testing program and began conducting random drug tests.

Recovery in the 1990s

At the 1990 Commonwealth Games, Canadians won four gold and six bronze medals. The next year, Michael Smith won silver in the decathlon and Atlee Mahorn took home bronze in the 200 m at the 1991 World Championships. Mark McKoy returned to competition in 1991 and won a gold medal in the 110 m hurdles at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, Canada’s first track and field gold medal in 60 years. (McKoy left Canada to run for Austria shortly after.) At the same Games, Guillaume Leblanc won silver in the 20 km race walk, and Angela Chalmers won bronze in the 3000 m.

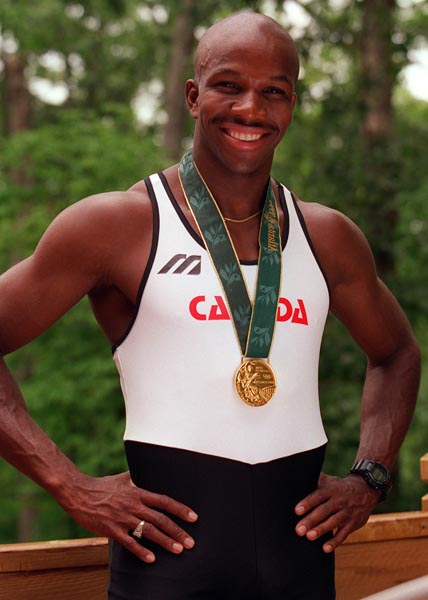

Donovan Bailey of Oakville, Ontario, and Bruny Surin of Montréal ran the fastest times ever on Canadian soil in July 1995 (9.91 and 9.97, respectively, for the 100 m) that Canadian track and field began to see a real turnaround from the scandals surrounding the Johnson affair.

Bailey and Surin continued their success at the world championships in Göteburg, Sweden, in August 1995. Bailey won the gold medal in the 100 m with a time of 9.97 and Surin was close behind, winning silver. The two combined with Robert Esmie of Sudbury, Ontario, and Glenroy Gilbert of Ottawa to win gold in the 4x100 m relay, which was Canada’s first-ever gold in an IAAF World Championships relay. Michael Smith’s bronze in the decathlon gave Canada its best team performance ever at the championships.

Canadian athletes continued to excel in sprint events at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. Bailey won the 100 m race against a strong field, setting a world record of 9.84, while Bailey, Robert Esmie, Glenroy Gilbert and Surin won the men’s 4x100 m relay in a spectacular finale.

The 2000 Sydney Olympics proved far less successful for Canadian track and field athletes: Bailey didn’t run the 100 m because of illness, and the men’s 4x100 m relay team failed to qualify. Mark Boswell, who was the 1999 world championship high-jump silver medallist, was hampered by rain. The highlights for Canada were Kevin Sullivan’s fifth-place finish in the 1500 m and Jason Turk’s sixth-place finish in the discus.

International Competition Since 2000

Canadian track and field athletes again failed to medal at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. However, hurdler Perdita Felicien had success at the world championships, winning gold in the 100m in 2003 and silver in 2007. With her 2003 victory, Felicien became the first Canadian woman to win an individual medal at the IAAF World Championships.

Another Canadian hurdler, Priscilla Lopes-Schliep, took bronze in the women’s 100m at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, while teammate Dylan Armstrong also took bronze in men’s shot put. Four years later, at the 2012 Olympic Games in London, Derek Drouin placed third in men’s high jump.

Since the 2012 Games, a number of strong track and field athletes have emerged in Canada. Sprinter Andre De Grasse burst onto the international scene in 2015, winning gold in the 100m and 200m at the Pan American Games in Toronto and bronze at the 2015 IAAF World Championships in Beijing. Although Donovan Bailey was the first Canadian to break the 10-second barrier in the 100m, De Grasse became the first to break both the 10-second barrier in the 100m and the 20-second barrier in the 200m in 2015. In June 2016, sprinter Aaron Brown also broke the 10-second barrier in the 100m while at the Olympic trials in Edmonton, Brendon Rodney became the second Canadian to break the 20-second barrier in the 200m. Canadians have also excelled in field events: at the 2015 world championships, Drouin took first in the high jump and Shawn Barber won the pole vault competition.

Olympic Medals in Athletics

|

Athlete |

Event | Medal | Games |

| George Orton | Steeplechase 2500 m (M) | Gold | Paris 1900 |

| George Orton | Hurdles 400 m (M) | Bronze | Paris 1900 |

| Étienne Desmarteau | Weight Throw 56lb (M) | Gold | St. Louis 1904 |

| Robert Kerr | 200 m (M) | Gold | London 1908 |

| J. Garfield MacDonald | Triple Jump (M) | Silver | London 1908 |

| Robert Kerr | 100 m (M) | Bronze | London 1908 |

| Con Walsh | Hammer Throw (M) | Bronze | London 1908 |

| Calvin Bricker | Long Jump (M) | Bronze | London 1908 |

| Edward Archibald | Pole Vault (M) | Bronze | London 1908 |

| George Goulding | Race Walk 10 km (M) | Gold | Stockholm 1912 |

| Duncan Gillis | Hammer Throw (M) | Silver | Stockholm 1912 |

| Calvin Bricker | Long Jump (M) | Silver | Stockholm 1912 |

| Frank Lukeman | Pentathlon (M) | Bronze | Stockholm 1912 |

| William Happenny | Pole Vault (M) | Bronze | Stockholm 1912 |

| Earl Thomson | Hurdles 110 m (M) | Gold | Antwerp 1920 |

| Percy Williams | 100 m (M) | Gold | Amsterdam 1928 |

| Percy Williams | 200 m (M) | Gold | Amsterdam 1928 |

|

Ethel Smith Fanny "Bobbie" Rosenfeld Jane Bell Myrtle Cook |

Relay 4x100 m (W) | Gold | Amsterdam 1928 |

| Ethel Catherwood | High Jump (W) | Gold | Amsterdam 1928 |

| Fanny "Bobbie" Rosenfeld | 100 m (W) | Silver | Amsterdam 1928 |

| James Ball | 400 m (M) | Silver | Amsterdam 1928 |

| Ethel Smith | 100 m (W) | Bronze | Amsterdam 1928 |

|

Alex Wilson Phil Edwards James Ball Stanley Glover |

Relay 4x400 m (M) | Bronze | Amsterdam 1928 |

| Duncan McNaughton | High Jump (M) | Gold | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Hilda Strike | 100 m (W) | Silver | Los Angeles 1932 |

|

Hilda Strike Lillian Alderson Mary Frizzell Mildred Frizzell |

Relay 4x100 m (W) | Silver | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Alex Wilson | 800 m (M) | Silver | Los Angeles 1932 |

|

Raymond Lewis James Ball Phil Edwards Alex Wilson |

Relay 4x400 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Alex Wilson | 400 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Phil Edwards | 800 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Phil Edwards | 1500 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1932 |

| Eva Dawes | High Jump (W) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1932 |

| John Loaring | Hurdles 400 m (M) | Silver | Berlin 1936 |

|

Aileen Meagher Dorothy Brookshaw Hilda Cameron Jeanette Dolson |

Relay 4x100 m (W) | Bronze | Berlin 1936 |

| Phil Edwards | 800 m (M) | Bronze | Berlin 1936 |

| Betty Taylor | Hurdles 80 m (W) | Bronze | Berlin 1936 |

|

Diane Foster Nancy MacKay Patricia Jones Viola Myers |

Relay 4x100 m (W) | Bronze | London 1948 |

| Bill Crothers | 800 m (M) | Silver | Tokyo 1964 |

| Harry Jerome | 100 m (M) | Bronze | Tokyo 1964 |

| Greg Joy | High Jump (M) | Silver | Montréal 1976 |

|

Angela Bailey Angella Issajenko France Gareau Marita Payne |

Relay 4x100 m (W) | Silver | Los Angeles 1984 |

|

Charmaine Crooks Dana Wright Jillian Richardson Marita Payne Molly Killingbeck |

Relay 4x400 m (W) | Silver | Los Angeles 1984 |

| Ben Johnson | 100 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1984 |

| Lynn Williams | 3000 m (W) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1984 |

|

Ben Johnson Desai Williams Sterling Hinds Tony Sharpe |

Relay 4x100 m (M) | Bronze | Los Angeles 1984 |

| Dave Steen | Decathlon (M) | Bronze | Seoul 1988 |

| Mark McKoy | Hurdles 110 m (M) | Gold | Barcelona 1992 |

| Guillaume Leblanc | Race Walk 20 km (M) | Silver | Barcelona 1992 |

| Angela Chalmers | 3000 m (W) | Bronze | Barcelona 1992 |

| Donovan Bailey | 100 m (M) | Gold | Atlanta 1996 |

|

Bruny Surin Carlton Chambers Donovan Bailey Glenroy Gilbert Robert Esmie |

Relay 4x100 m (M) | Gold | Atlanta 1996 |

| Priscilla Lopes-Schliep | Hurdles 100 m (W) | Bronze | Beijing 2008 |

| Dylan Armstrong | Shot Put (M) | Bronze | Beijing 2008 |

| Derek Drouin | High Jump (M) | Bronze | London 2012 |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom