Treaties 1 and 2 were the first of 11 Numbered Treaties negotiated between 1871 and 1921. Treaty 1 was signed 3 August 1871 between Canada and the Anishinabek and Swampy Cree of southern Manitoba. Treaty 2 was signed 21 August 1871 between Canada and the Anishinaabe of southern Manitoba (see Eastern Woodlands Indigenous Peoples). From the perspective of Canadian officials, treaty making was a means to facilitate settlement of the West and the assimilation of Indigenous peoples into Euro-Canadian society (see Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada). Indigenous peoples sought to protect their traditional lands and livelihoods while securing assistance in transitioning to a new way of life. Treaties 1 and 2 encapsulate these divergent aims, leaving a legacy of unresolved issues due to the different understandings of their Indigenous and Euro-Canadian participants.

This article is a full-length entry about Treaties 1 and 2. For a plain-language summary, please see Treaties 1 and 2 (Plain-Language Summary).

The Impetus for Treaties 1 and 2

Before Confederation in 1867, the vast watershed of Hudson Bay (then called Rupert’s Land) had been the domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). For nearly two centuries, since receiving its charter from the British Crown in 1670, the corporation and its competitors had traded furs with Indigenous peoples in the interior of North America, establishing distinctive protocols for cementing commercial and diplomatic ties in the process (see Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

After Confederation on 1 July 1867, the new country of Canada set out to acquire the huge tract of land, then known as Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territories. In November 1869, the HBC sold its lands in the western interior to the British Crown, which intended to transfer them to Canada the following year. The Indigenous inhabitants of Rupert’s Land were not consulted about the sale. The Métis resisted, forming a provisional government under Louis Riel. In the wake of the Red River Resistance, the Canadian government, through the Manitoba Act, guaranteed 1.4 million acres for the Métis and their descendants. However, no negotiations or settlements were reached with First Nations peoples of the region, including the Anishinaabe, whose lands were brought under Canadian jurisdiction, along with Manitoba, as the “North-West Territories” in July 1870.

Indigenous peoples in Manitoba had been advocating for a treaty with the federal government since the late 1850s. In 1857, Chief Peguis of the Anishinaabe petitioned the Aborigines’ Protection Society in the United Kingdom for a “fair and mutually advantageous treaty” for his people. The HBC’s “sale” of Rupert’s Land had caused alarm, particularly since Indigenous peoples had never recognized their trading partner as having any jurisdiction over them or their lands. Peguis and his son, Henry Prince, published an “Indian Manifesto” in the settler newspaper The Nor’Wester, insisting that anyone who cultivated Indigenous land would have to make annual payments in recognition of their Aboriginal title (see Indigenous Land Claims in Canada). In the context of unrest and uncertainty, the new lieutenant-governor of Manitoba, Adams G. Archibald, was sent west in August 1870. Shortly after he arrived, he met with a delegation led by Henry Prince, promising to open treaty negotiations with them the following year.

Archibald was concerned with facilitating settlement of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. In particular, he wished to secure title to the area around the south end of Lake Winnipeg — where saw mills had already been established — and to open the fine agricultural lands west of the Red River Valley. Archibald explained to Secretary of State Joseph Howe that a treaty was a legal imperative, “We were all of [the] opinion that it would be desirable to procure the extinction of Indian title, not only to the lands included within the Province [of Manitoba], but also to so much of the timber grounds east and north of the Province, as were required for immediate entry and use, and also of a large tract of cultivable ground, west of the Portage.”

A group of 73 “principal headmen” around Portage la Prairie met in spring 1871 and passed a resolution asserting, “We never have yet, seen or received anything for the land and the woods that belong to us, and the settlers use to enrich themselves.” A warning to settlers was posted on a Portage la Prairie church door. Other Indigenous peoples likewise attempted to fend off settlers.

Secretary of State Howe appointed Wemyss Simpson as an Indian commissioner, charging him with obtaining a treaty for lands between Thunder Bay and Fort Garry. Howe’s instructions to Simpson are evidence of the great stress that the Canadian government placed on frugality. Howe wrote Simpson: “It should therefore be your endeavour to secure the cession of the lands upon terms as favourable as possible to the government.” Howe’s instructions to Simpson also reflect official awareness that the first treaty to be negotiated with Indigenous peoples in the Canadian West would set a precedent. Howe set the maximum annuity at $12 per year for a family of five. Archibald would later echo this sentiment back to Howe while reporting on the Treaty 1 negotiations: “I look upon these proceedings, we are now initiating, as important in their bearing upon our relation to the Indians of the whole continent.”

Commissioner Simpson first sought and failed to negotiate a treaty with the Indigenous peoples in northwestern Ontario, an area later covered by Treaty 3. Simpson joined Lieutenant-Governor Archibald in Manitoba in July 1871, where they decided to pursue two treaties in order to avoid the delays involved in gathering a larger group as well as the expense of feeding them. The first treaty, which became known as Treaty 1, was to be made at the “Stone Fort” (or Lower Fort Garry), and the second, Treaty 2, was to be negotiated at Manitoba Post on Lake Manitoba. The officials then issued a proclamation inviting Indigenous people to attend negotiations at Fort Garry on 25 July 1871.

Negotiating Treaty 1

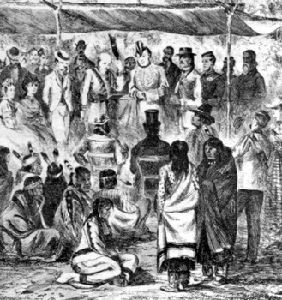

The negotiations for Treaty 1 did not start until 27 July 1871, after approximately 1,000 Indigenous attendees, including men, women and children, had formed an impressive camp of roughly 100 tents in a semi-circle around Fort Garry. James McKay, a Métis member of Manitoba’s Executive Council, was retained as interpreter.

Treaty 1 is very unusual among the Numbered Treaties in that The Manitoban, a Winnipeg weekly, published daily transcripts of the protracted, eight-day negotiation. In his opening remarks, Archibald assured the attendees that Queen Victoria, whom he referred to in kinship terms as the “Great Mother,” wanted to deal fairly with them: she desired Indigenous peoples to adopt agriculture, but she would not force them to make drastic changes. Archibald attempted to introduce the concept of reserves, but stressed that Indigenous people would still have the freedom to pursue their traditional ways of life on the surrendered territory, until a vaguely defined future time when those lands were “needed for use”:

Your Great Mother, therefore, will lay aside for you ‘lots’ of land to be used by you and your children forever. She will not allow the white men to intrude upon these lots. She will make rules to keep them for you, so that as long as the sun shall shine, there shall be no Indian who has not a place that he can call his home […]

Till [sic] these lands are needed for use, you will be free to hunt over them, and make all the use of them which you have made in the past. But when lands are needed to be tilled or occupied, you must not go on them any more.

When the Indigenous negotiators returned after deliberating for two days, they presented a list of demands that Simpson and Archibald considered “exorbitant.” They desired reserves in proportion of “three townships per Indian,” which Archibald estimated would have amounted to about two-thirds of the province. As Archibald put it to Secretary of State Howe in a letter on 29 July, “The Indians seem to have false ideas of the meaning of a reserve. They have been led to suppose that large tracts of ground were to be set aside for them as hunting grounds, including timber lands, of which they might sell the wood as if they were proprietors of the soil.”

Archibald insisted to negotiators that he was prepared to give them reserves based on the formula of 160 acres per family of five, consistent with the provisions for homesteads for white settlers outlined in the Dominion Lands Act, of which Archibald was an architect. However, it is clear from the proceedings that any explanation was muddled by Archibald’s and Simpson’s repeated promises that the signatories would be able to continue using the land in the surrendered tract for traditional pursuits, such as hunting, trapping, and fishing. Moreover, the lieutenant-governor further confused the terms by promising offhandedly that the land requirements of future generations “will be provided for further West,” and that “whenever the reserves are found too small the Government will sell the land, and give the Indians land elsewhere.”

Mixed with these almost careless reassurances was an underlying threat: Archibald informed Indigenous negotiators that “whether they wished it or not, immigrants would come in and fill up the country, […] and that now was the time for them to come to an arrangement that would secure homes and annuities for themselves and their children.”

One Indigenous negotiator pointed out that granting 160 acres for Indigenous and Euro-Canadian peoples alike was not equitable, as the typical settler had the capital to establish a farm. Another individual, Ay-ee-ta-pe-pe-tung, became so disillusioned by the proceedings that he threatened to “go home without treating,” even though the Queen’s subjects might go on his land. “Let them rob me,” Ay-ee-ta-pe-pe-tung asserted.

The impasse was broken on the last day of proceedings, 2 August. After six days, Henry Prince still wondered, “How are we to be treated? The land cannot speak for itself. We have to speak for it; and we want to know fully how you are going to treat our children.” How would the Queen help the signatories learn how to cultivate the land? “They cannot scratch it — work it with their fingers,” Prince pointed out, “What assistance will they get if they settle down?” According to the Manitoban, the Indigenous negotiators were reassured by the Crown’s representatives that “the Queen was willing to help the Indians in every way, and that besides giving them land and annuities, she would give them a school and a schoolmaster for each reserve, and for those who desired to cultivate the soil ploughs and harrows would be provided on the reserves.”

On 3 August 1871, Treaty 1 was signed at Fort Garry. The tense, eight-day proceedings reflected both the difficulty in reaching mutual understanding on Euro-Canadian concepts such as “reserves” and “surrender,” and the fact that the Indigenous negotiators pressed hard to secure the reserves they needed for the future. Far from being the actions of a benevolent government acting with wise foresight in order to circumvent unrest, the treaty negotiations were, as historian D.J. Hall has argued, “badly handled by an ill-prepared government and its officials.” It was the Indigenous participants who had forced changes to the government’s plan and raised the issues that would appear in subsequent treaties, issues revolving around how Indigenous people would secure the resources needed for the future.

Written Terms of Treaty 1

Treaty 1 was signed by government agents Lieutenant-Governor Adams G. Archibald, Commissioner Simpson, Major A.G. Irvine, and eight witnesses. The signatories for the Anishinaabe and the Swampy Cree were: Red Eagle (Mis-koo-ke-new, or Henry Prince); Bird Forever (Ka-ke-ka-penais, or William Pennefather); Flying Down Bird (Na-sha-ke-penais); Centre of Bird’s Tail (Na-na-wa-nanan); Flying Round (Ke-we-tay-ash); Whip-poor-will (Wa-ko-wush); and Yellow Quill (Os-za-we-kwun).

The Governor General in Council formally ratified the treaty on 12 September 1871. Each band was to receive a reserve large enough to provide 160 acres for each family of five (or in like proportion for smaller or larger families). Each man, woman, and child was to be given a gratuity — or one-time payment — of three dollars, and a yearly annuity totalling $15 per family of five. The government also agreed to maintain a school on each reserve and to prohibit the introduction or sale of liquor on reserves.

For their part, the Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree were required in the written text to “cede, release, surrender, and yield up to her Majesty the Queen” a tract of land described in detail in the treaty: a substantial amount of present-day southeast and south-central Manitoba, including the Red River Valley, and stretching north to the lower parts of Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg and west along the Assiniboine River to the towns of Portage la Prairie and Brandon.

The Signing of Treaty 2 and Treaty Terms

After concluding negotiations for Treaty 1, Commissioner Simpson, Lieutenant-Governor Archibald, and James McKay, along with the clerk of Manitoba’s Legislative Assembly, Molyneux St. John, went to Manitoba Post, an HBC trading post on the southwest side of Lake Manitoba, to complete Treaty 2.

Treaty 2 was signed on behalf of the Anishinaabe by Mekis, Sou-sonce, Ma-sah-kee-yash, François (Broken Fingers), and Richard Woodhouse. In the written text of the treaty, the Anishinaabe agreed to “cede, release, surrender and yield up to Her Majesty the Queen, and Her successors forever” a large tract of very valuable land to the west and north of Manitoba as it existed in 1871, and three times as large as the province. It was all the land that was likely to be required by settlers for some time to come. In return, each band would receive a reserve large enough to provide 160 acres for each family of five.

It is possible that the Indigenous negotiators at Treaty 1 understood the treaty as a promise to share the land with newcomers, each group pursuing its livelihood without interference, particularly given how government treaty negotiators emphasized the Indigenous ability to continue to hunt and fish on ceded tracts and muddled the concepts of “surrender” and “reserves.” These mutual misunderstandings may have been repeated during the signing of Treaty 2.

The other written terms of Treaty 2 mirrored those of Treaty 1 with regards to gratuities, schools on reserves, and the prohibition of the sale of liquors on reserves. The Governor General in Council ratified Treaty 2 on 25 November 1871.

The “Outside Promises” of Treaties 1 and 2

In the written text of the treaty, no provisions were included for the agricultural implements, clothing, and animals promised toward the end of negotiations. These unfulfilled treaty terms became known as the “Outside Promises” because they were not ratified along with the main text of Treaty 1 or Treaty 2, despite the fact that Chief Henry Prince and others refused to sign the treaty under Archibald, and Simpson had agreed to put the additional promises in writing. By February 1872, complaints from Indigenous peoples that the terms of the treaty had not been fulfilled reached Lieutenant-Governor Archibald. Archibald blamed Indian Commissioner Simpson and the fact that there was no resident Indian commissioner in Manitoba and the North-West Territories. In June 1873, Ottawa sought to amend this lack of bureaucratic infrastructure by appointing Joseph Provencher as a resident Indian commissioner in place of Simpson.

Complaints from bands about unfulfilled promises continued, with such bands as Pembina, Portage la Prairie, and St. Peter’s refusing to accept their annuity payments in 1872. Molyneux St. John, who had witnessed Treaty 2 for the government, sent Ottawa a list enumerating the Outside Promises, which he said had been written by Archibald. St. John acknowledged the paradox in asking Indigenous peoples to take up agricultural pursuits without providing them the means of doing so. He recommended that the government remedy the situation.

The federal government did not resolve the issue until 30 April 1875, when an order-in-council was passed. The order stipulated that “the written Memorandum attached to Treaty No. 1 be considered a part of that Treaty and of Treaty No. 2, and that the Indian Commissioner be instructed to carry out the promises therein contained insofar as they have not yet been carried out.” The unfulfilled terms included the provision of animals such as bulls, cows, boars, and sows, and equipment such as plows and harrows, and buggies. In addition, the annuity in Treaties 1 and 2 was raised from three to five dollars per year.

Issues of Modern-Day Interpretation

Archibald and Simpson also failed to include a provision on hunting and fishing rights in the written texts of Treaties 1 and 2, although Archibald had verbally promised that Indigenous peoples would retain such rights in the ceded territory. In future decades, the settler government of Manitoba would begin to restrict Indigenous peoples’ access to game and fish, in violation of these promises.

The Supreme Court of Canada has found that the written text alone cannot grant an understanding of the “spirit” of the treaties: the courts must now examine the historical context and the perception that each party likely had of the agreement. Anishinaabe lawyer and author Aimée Craft has pointed out that it is unlikely the Indigenous participants understood the concept of “surrender,” particularly when the Euro-Canadian negotiators repeatedly assured the Indigenous signatories that they would be able to continue using the natural resources on the surrendered tract — an idea seemingly incompatible with surrender.

Likewise, it is possible that the Euro-Canadian negotiators failed to understand perspectives based in Anishinaabe concepts of law, or inaakonigewin, that the Indigenous participants brought to the treaty. Craft has explained how Anishinaabe concepts of a sacred relationship with the land make it difficult to talk about ownership or surrender. The Indigenous perspective on the kinship terms so often utilized by the Euro-Canadian negotiators — “the Great Mother” for the Queen — likely involved retaining far more autonomy and equality vis-à-vis Europeans than Archibald, Simpson, or the burgeoning policies of the federal government would allow. Likewise, the Euro-Canadian negotiators would not have grasped ideologies about sharing land and not interfering with another’s livelihood that the Anishinaabe would have brought to the negotiating table. On this ground of mutual misunderstanding, it is likely that the meaning of Treaties 1 and 2, like that of many, will continue to be debated.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom