Canadian English has spawned many expressions for headgear. Beaver hats, Mountie hats and Tilley hats all originated in Canada. “Christy stiffs” were a Canadian variety of derby hat. A “Pangnirtung hat” (also known as a “Pang hat”) is the name of a brightly coloured wool cap from the eastern Arctic, often with earflaps and a tassel (see Nunavut). But the most iconic item of Canadian headwear is arguably the tuque.

Tuques are not unique to Canada. Some form of knitted cap, traditionally made of wool, keeps people’s heads warm in various parts of the world. English-speakers in other countries seldom or never refer to tuques. In Britain a common word is “balaclava” (referring to a battle in the Crimean War). In the United States, the phrase “stocking cap” is frequently used. Australians prefer the term “beanie.”

Where does the word "tuque" come from?

The word “tuque” entered Canadian English from French. Although the Breton, Spanish and Italian languages all contain similar terms, those words don’t always refer to knitted caps. (The Spanish word toca,for instance, meant a woman’s headdress.) In English, “toque” can also refer to a round, brimless hat worn by a woman, to a small cap or bonnet for either a man or a woman, and to the tall white hat traditionally favoured by chefs. One of the qualities that formerly distinguished a tuque from other types of winter headwear was its long tassel, or pom-pom; most tuques today are tailless.

Atwater group. Members of Tuque Bleu Toboggan Club in Montreal, Quebec. Photo taken around 1880, courtesy of the McCord Museum. Gift of Mrs. W. R. Dean.

Cities often lend their name to physical objects. Nanaimo bars, Winnipeg couches, and Montreal smoked meat are a few Canadian examples, along with Pangnirtung hats and Cowichan Sweaters. The tuque reverses this process. A tuque may be the only type of hat in Canada that has given its name to a place. La Tuque, a municipality located in central Quebec, northwest of Quebec City, has been known by that name since before 1822, when a trader and early settler named François Verreault reported on a difficult portage that he knew by the Innu name of Ushabatshuan (meaning ‘the rapids too strong to jump’). “The voyageurs call it La Tuque,” Verreault wrote, “due to a tall mountain whose peak resembles a tuque. The portage is a league long, and climbs steep slopes.”

Symbolism in Quebec

Illustrations of the Patriotes – those who rebelled against British rule over Lower Canada in 1837-8 – often depict a tuque-wearing man with a pipe clenched in his mouth and a musket held in his hands. The image was created, several decades after the rebellion, by the Montreal artist and cartoonist Henri Julien. Sympathizers of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) adopted the image during the October Crisis of 1970. To this day it remains a popular symbol among francophone nationalist groups in Quebec. In the popular imagination, at least, the Patriotes sported a blue tuque (which can also be called a bonnet in French) – hence the name of what was, for more than a century, Montreal’s leading racing track for thoroughbred horses, Blue Bonnets Raceway.

Within Quebec, the tuque sometimes has a contested symbolic meaning. In August 1948 sixteen young Quebec artists, including the painters Paul-Émile Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, published a manifesto entitled Refus Global (”Total refusal”). It served as a wake-up call to young Quebecers who were growing weary of the power held over society by the Roman Catholic church. The manifesto rejected traditional authority in favour of “resplendent anarchy,” saying that “The shades of hopeless bondage give way to pride in a freedom that vigorous struggle can obtain. To hell with the clergy and the tuque!” These artists were keen to enter an international future, and to them the tuque represented the rural past.

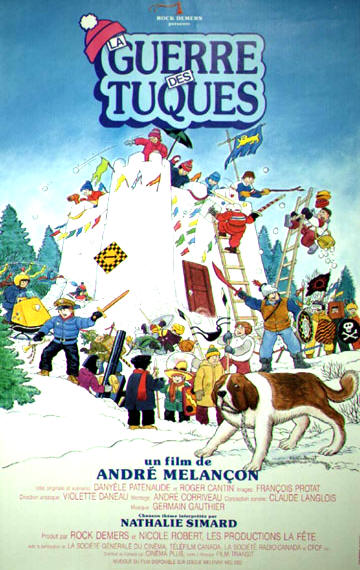

One of the most popular family movies ever made in Canada was a 1984 film entitled La Guerre des tuques. It portrayed an extended fight between two rival groups of children in a small Quebec town. No doubt the familiar image of tuque-wearing Patriotes played a part in the choice of name. But when the movie was released the following year in English, it was titled The Dog Who Stopped the War. In French, the image of tuques continues to have a kind of symbolic resonance that is lacking in English.

La guerre des tuques. Courtesy of Rosalie Maxime, Flickr.

Tuques and winter sports

Speakers of Canadian English did not exactly rush to adopt the word. For a long time, its uses remained limited. An entry in the Oxford English Dictionary, dating from 1915, notes that a tuque was “formerly the characteristic winter head-dress of the Canadian ‘habitant’” and goes on to say that it is “now chiefly worn as part of a toboggan or snow-shoe club costume.” Only gradually did the word spread beyond winter sports into daily life. Even now, many Newfoundlanders prefer to use other terms, notably the American “stocking cap” or simply “hat" (see Newfoundland and Labrador.)

The connection between tuques and sports took on a new life in the early 21st century, as several junior hockey clubs in Canada organized an annual “Tuque and Teddy Bear Toss,” usually held in the weeks leading up to Christmas. When the home team scores its first goal of the night, fans are encouraged to throw a stuffed toy, a tuque, or both onto the ice. The donations are collected and given away to local charities.

What is the proper spelling of "tuque"?

What remains unclear, however, is how this word should be spelled. This article has preferred the Quebec spelling “tuque,” which makes phonetic sense. All across English Canada, the word is pronounced to rhyme with “duke” rather than “smoke”. In French, it rhymes with “Luc”. But the older and still more common spelling in much of English Canada is “toque” – despite the confusion that can arise between knitted caps, brimless hats, bonnets and chef’s hats, all of which sometimes demand the same term. For example, in her 2015 book The Wild in You, the distinguished poet Lorna Crozier described meeting a photographer in British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest by saying he had “a chewed-up wool toque pulled low on his forehead.” As it happens, Crozier had been sent to the area to write a piece for an online travel magazine named Toque and Canoe.

To complicate matters further, many Canadians prefer the compromise spelling of “touque.” Newspapers are split on this issue. In the early months of 2019, for instance, a festival organizer “tipped his touque” in the Victoria Times-Colonist, a missing man “was last seen wearing a tuque” in the Ottawa Citizen, and a protester wore “a toque emblazoned with a profane message” in the Regina Leader-Post. We all know a tuque when we see one, but we can’t agree on how to spell the word.

Children playing at the Festival des Voyageurs in Winnipeg, Manitoba. 2009. Photo courtesy of Simply Col, Flickr.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom