The following article is part of an exhibit. Past exhibits are not updated.

This exhibit features four great Canadian achievements in urban transportation.

In 2016, the Montréal metro turns 50 (it opened in 1966), while two other light rail transit systems — Calgary’s CTrain (1981) and Vancouver’s SkyTrain (1986) — turn 35 and 30 respectively. Finally, Canada’s oldest subway, which has served Toronto since 1954, turns 62.

Transporting hundreds of thousands of people per day, these subways and light rail transit (LRT) systems have significantly changed the design and stimulated the development of the cities that built them. The Canadian experience is nevertheless relatively recent compared to that of many European and American cities. Budapest, for example, opened its original 11-station subway in 1896; it would take almost another 60 years for a Canadian city to do the same.

From inception to completion, from progress to setback, these projects offer a fascinating view of urban transportation planning. Though marked by political wavering, cost overruns and construction delays, they are a testament to four cities’ will to revitalize their economy, innovate and even stand out as models for the rest of Canada and the world.

Streetcar Era

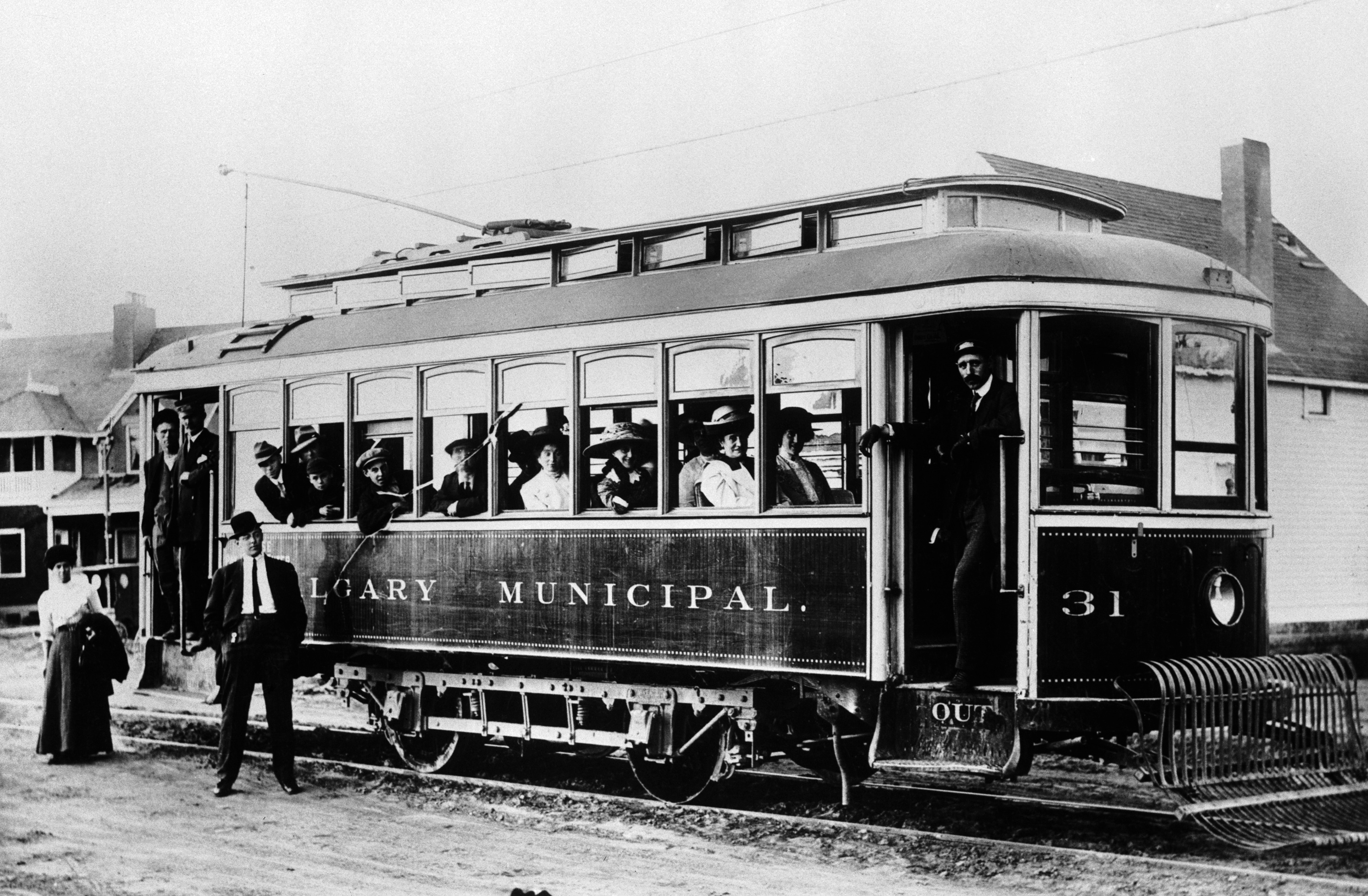

The history of urban rail transit in Canada dates back to the mid-19th century. Toronto had horse-drawn streetcars by 1845. Montréal followed suit in the 1860s, and it didn’t take long for other Canadian cities to get “on track.”

The spread of industrialism and the growing size of cities set the stage for the further development of urban transportation systems. It was no longer possible for many city dwellers to live within walking distance of work. The invention of the electric railway in the late 19th century revolutionized transportation, and efforts quickly turned to adapting this technology for city life. With the invention of the trolley pole, which permitted the efficient and safe supply of electric power to streetcars from overhead wires, animal power became a way of the past.

Canada was one of the first countries to take advantage of this technology. In 1886, Canada’s first electric railway line was established in Windsor along 2.4 km of track. Vancouver followed in 1890, Winnipeg in 1891, Montréal, Hamilton and Toronto in 1892, Edmonton in 1908, Calgary in 1909 and Regina in 1911. By the start of the First World War, 48 Canadian cities had urban railway systems.

Early Plans

Early in the 20th century, Canada’s two largest cities considered building subways like those of London (1890), Paris (1900) and New York (1904). Circumstances would nevertheless dictate a delay in serious examination of these projects in Toronto and Montréal until the end of the Second World War.

By the end of the war, the majority of public transit systems in Canada were worn out and required extensive new investment. Most Canadian cities, including Calgary (1947), Vancouver (1955) and Montréal (1959), abandoned streetcar services, replacing them with modern trolleybuses and motorbuses. Only Toronto opted to keep its streetcars.

Yet the growing traffic problems in cities — owing to the rapid increase in the number of automobiles on the road and the accompanying decline in public transit ridership — was one of the main concerns brought forward by the people and organizations who argued for the construction of a subway or light rail system. In a Toronto referendum held in early 1946, residents approved the construction of a subway line along Yonge Street from Union Station to Eglinton Avenue.

In 1961, the Québec provincial government granted the City of Montréal permission to build a subway. Mayor Jean Drapeau unveiled the original route, and construction began in spring 1962. In 1977, Calgary City Council approved a proposal for an LRT system. Much less expensive to build than a subway, an LRT also had lower operating costs than a busway system and promised to significantly relieve congestion on city roads. Vancouver, which briefly courted the idea of a subway in the late 1960s, began to consider an LRT in 1975. In the end, however, it selected a new, largely untested Canadian technology called Advanced Light Rapid Transit (ALRT) in 1980.

Network Construction

Toronto officially began building the Yonge subway line on 8 September 1949. Most of the original 7.4 km stretch was constructed using the “cut and cover” technique. Much less expensive than tunnelling, this method involved digging a deep trench and covering it up with planks as construction proceeded.

Construction of the Montréal metro also involved digging a trench — to a depth of 40 to 60 feet, sometimes deeper. City officials took measures to protect certain major arteries from the inconveniences that construction would cause. For example, they decided not to build the metro under Sainte-Catherine Street, but rather under De Maisonneuve Boulevard, a new artery that was still under construction at the time. Using new technology — cars that ran on rubber tires instead of the traditional steel wheels on rails — Montréal differentiated its subway system from Toronto’s.

The original CTrain line included a 10.9 km route that ran north from Anderson Station to downtown and a 2 km free-fare zone along 7 Avenue in the downtown core. While this system operated primarily aboveground, trains passed underground in certain places. The original Vancouver ALRT line cost approximately $854 million and ran 21.4 km through Vancouver, Burnaby and New Westminster. The SkyTrain operated primarily on an elevated guideway (hence its name), but with some sections running underground such as through the Dunsmuir Tunnel, built in the 1930s by the CPR.

Opening Day

Toronto: 30 March 1954 Montréal: 14 October 1966 Calgary: 25 May 1981 Vancouver: 3 January 1986

The opening of both Montréal’s metro and Vancouver’s SkyTrain coincided with world’s fairs — international events celebrating culture and innovation. Since their inception in the mid-19th century, these expositions have served to introduce the world to new gadgets and technology. The telephone was unveiled at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, motion pictures at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the ice cream cone at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. In 1986, it was Vancouver’s turn to take centre stage. Dubbed Expo 86 and given the tagline, “World in Motion, World in Touch,” the fair had a transportation theme. A life-size model of the SkyTrain cycled through the fairgrounds, introducing the world to the first driverless urban rail system.

While Canada’s 100th birthday, not the Montréal metro, was the impetus for Expo 67, the upcoming fair put political will behind the train’s construction. It opened on 14 October 1966, in time for the exposition the following year. The Expo’s locations — an expanded Île Sainte-Hélène as well as a new island called Île Notre-Dame — were created using at least 25 million tons of dirt and rock excavated to build the metro.

Network Expansions

The transportation networks in all four cities have grown substantially since their first day of operation. Toronto’s subway, for example, has grown from 12 stations on a single 7.4 km line to 69 stations over four lines and 68.3 km. Just as the world’s fairs provided the necessary momentum to open Vancouver and Montréal’s rail systems, the Olympics spurred expansions. The eastern portion of Montréal’s Green Line opened in time for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games, connecting the existing network with Olympic Park. Similarly, in advance of the 1988 Winter Games, CTrain Route 201 was extended northwest to the University of Calgary, the site of the Olympic Oval, athletes’ village and McMahon Stadium — the venue for the opening and closing ceremonies. More recently, the SkyTrain’s Canada Line opened in time for the 2010 Winter Olympics, connecting Vancouver to Richmond.

Public Art and Urban Transit

Among urban transit systems in Canada, public art has figured most prominently in Montréal. From the beginning, great care was taken to give each station a unique architecture and design, and to display the works of Québec artists of various disciplines such as Frédéric Back, Jordi Bonet and Marcelle Ferron. In focusing on public art, Montréal sought to differentiate itself from Toronto and other North American subway systems. The city also aimed to attract Montrealers to the metro at a time when many of them were abandoning public transit in favour of automobiles.

Conversely, both Calgary and Vancouver — and to a lesser extent, Toronto — aimed for uniformity in the construction of their original lines. For example, the SkyTrain’s Expo Line was built using a “kit of parts,” an inexpensive system of steel hoop trusses and concrete box beams assembled for each station. Art became more of a priority in later expansions — stations on the Canada Line include space for artwork, for instance, and new CTrain stations are subject to a 2004 policy that requires 1 per cent of spending be dedicated to public art.

While the original stations on Toronto’s Yonge line were also built uniformly — each featured glass tiles in a solid colour and contrasting trim — the 1978 Spadina extension featured art commissioned for each station. This tradition has continued, as artwork is now an integral part of both new and refurbished stations.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom